1/7

conversation about notation with Cristián Alvear & Radu Malfatti; notation from Christoph Herndler; reviews

Houston, Texas’ Nameless Sound performance series continues celebrating its 20th anniversary by diving into archives of previously unreleased sound, video, and stories from musicians with deep connections to the series. The most recent edition explores relationships between The Aural and The Visual and features Keith Rowe and Loren Connors solos in the Rothko Chapel, Peter Brötzmann at The Hill of James Magee, Cristina Carter + Heather Leigh, Ran Blake’s Film Noir, and more. Previous profiles include Joe McPhee, Maggie Nichols, Alvin Fielder, and Pauline Oliveros.

IM-OS, a journal featuring writings on open scores, recently released a new issue with a focus on Scratch Orchestra and their practice.

Recordedness, which explores the nature of recording through interviews, recently released new interviews, including John Butcher by Frantz Loriot, Eliot Cardinaux by Sean Ali, Michael Coleman by Sam Kulik, Jason Kahn by Jason Kahn, Al Karptenter & Mattin by Yan Jun, and Cecilia Lopez by Joe Moffet.

$5 suggested donation | harmonic series will always be free with no tiers or paywalls. This approach is lifted from common practices in experimental music communities of openness, inclusivity, and accessibility in their performances. Similarly it is now lifting the common practice of suggested donations. If you have the means and find yourself spending an hour or more reading an iteration of the newsletter, discovering music you enjoy in the newsletter, dialoguing your interpretations with those in the newsletter, or otherwise appreciate the efforts of the newsletter, please consider donating to it. More or less is equally appreciated. Disclaimer: harmonic series LLC is not a non-profit organization, as such donations are not tax-deductible.

annotations expanded

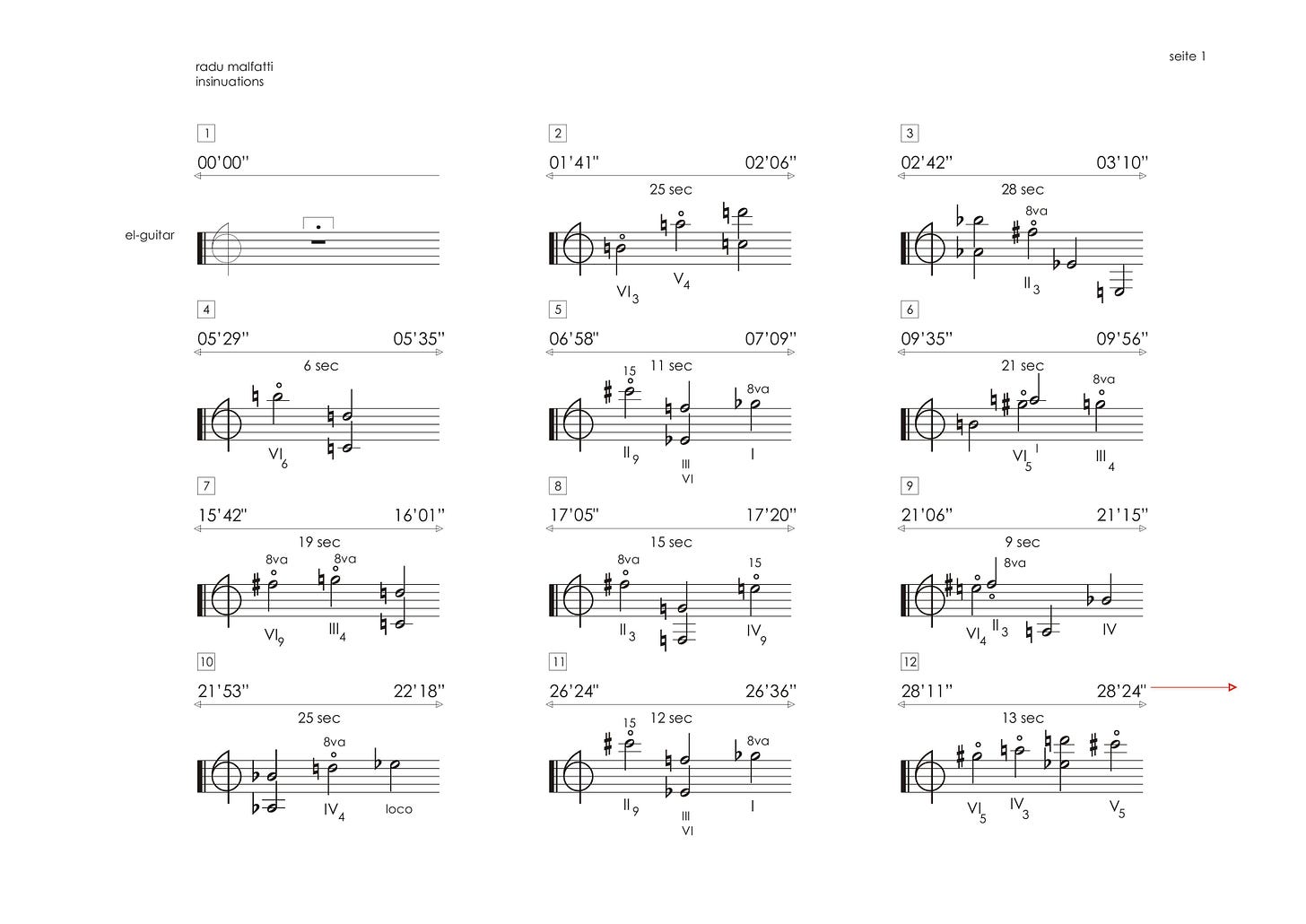

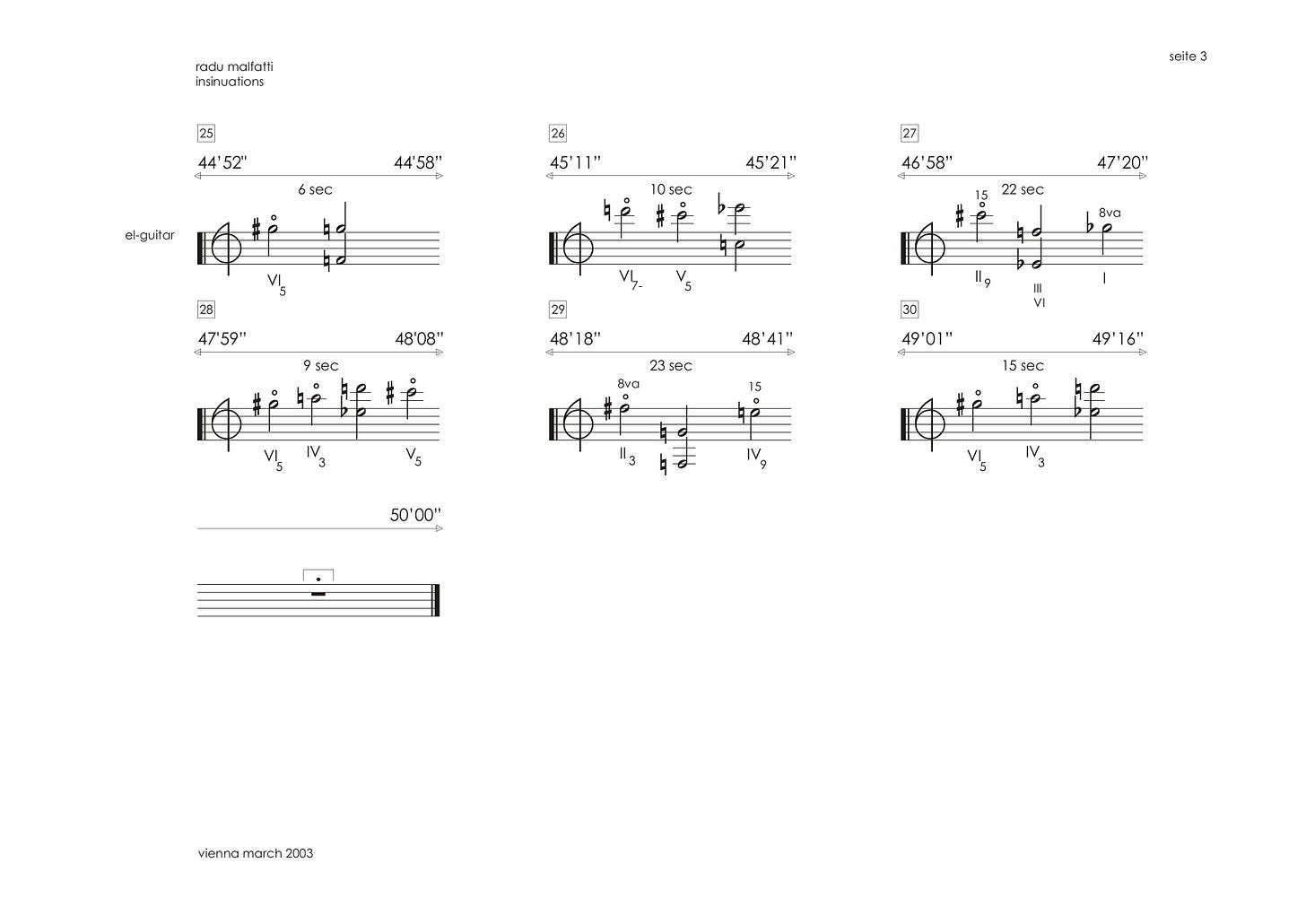

In harmonic series 1/4, Cristián Alvear discussed his approach to interpretation, touching on issues around resisting habit, a common bias against performers as trained monkeys, authenticity, and the composer-performer chain (concerning the latter issues, Cristián pointed me towards an interesting exchange with a traditional perspective towards interpretation that gives a lot of weight to the composer’s intentions in the comments of his performance of John Cage’s One7). Shortly after that conversation, Cristián asked me to interpret the Radu Malfatti composition Insinuations without having heard it to demonstrate the tensions that performers navigate in realizing a sound result from the score and its notation. This is quite different from any interpretative process in the ‘annotations’ portion of the newsletter, which so far has been in relation to a recording. After thinking about how I might interpret the score for a bit and only then listening to the recording of it, Cristián and I talked about the experience over video chat, significantly expanding upon the issues introduced in our previous conversation. I also gathered some thoughts around the score from Radu through email exchanges, and some of my own reflections are interspersed among the conversations.

I encourage readers to think about how they might interpret the score for Insinuations before listening to the recording of it or reading the conversation. Don’t get too caught up on the specific tones, but rather think about the form or shape of what you might perform.

All scores copied in this newsletter are done so with permission of the composer for the purpose of this newsletter only, and are not to be further copied without their permission.

Radu Malfatti - Insinuations (2003)

Cristián Alvear: Hey, Keith!

Keith Prosk: How’re you doing?

CA: I’m doing OK. I’m a little tired. I had a long period of intense work.

KP: Oh, man. And it’s starting to be winter, right now, right?

CA: Yeah. Real cold.

KP: Yeah, long days. I remember, you know, obviously not making music or doing anything PhD related but, yeah, working long days in the winter is never much fun. You wake up, go to work when it’s dark, come back home when it’s dark.

CA: Yeah, yeah, that’s it, that’s it. And, well, Santiago’s super cold in winter. It’s really really cold. We have the mountain range right next to the city. And Santiago’s in a valley, it’s surrounded by mountains, so it’s kind of like being inside a refrigerator.

KP: Yeah yeah. But, yeah, thanks so much for sending along Insinuations. Sorry it took a bit for me to finally sit down with it, take a good listen. How do you wanna talk about it?

CA: I don’t know. Maybe let’s just start by, maybe, I don’t know, we can discuss about what you thought should be the interpretation for notation. And we can take it from there and discuss that a little bit.

KP: When I first looked at it, I think the thing that I was really fixated on were the time arrows. So I guess with the arrows going either way, from the beginning of the composition or from the beginning and ends of each sounding segment…

CA: yeah, it’s kind of a time frame.

KP: yeah, like even though the duration and times are set, I was kind of importing the fixed meaning or my own interpretation of arrows as a continuation, so I really wanted the sounding to continue. And I kept on trying to figure out ways to make a silence while still being sounded so… [laughs]

CA: that’s pretty difficult [laughs]

KP: yeah, so what I came up with was like… my very first inclination, just cause I mess around with my wife’s instruments, was what if in the midpoint between segments you put something like an ebow or something on the strings and you’ve got this vibration going but it’s not actually audible until the designated durations. But I think that would be pretty impossible just ‘cause it’s a sequence of tones instead of a held chord or something like that.

CA: Doing that, it’s impossible. For each chord, you need the same amount of ebows as frequencies are on the chord. So sometimes you need one, sometimes three, it depends on the chord, so it’s pretty difficult to do.

KP: Yeah, and then I guess another thing that I came up with involved maybe hammering and damping… someway conveying the harmonic character of a segment before it came in and then undamping to let the vibrations go, become a bit more audible, and then damping it again. I think just with the arrows, I really wanted something of the sound to show up before and after the sounding segment.

CA: Yeah, I know what you mean. Well, the thing is that... what is interesting about what you’re saying is that, well, the notation is just not the staff and the notes on it, no? So, you have instructions, and instructions… well, maybe something before that. For notation, in experimental music, you have always a tension between what’s descriptive in terms of notation and what is prescriptive in terms of notation. The descriptive aspect of notation is a bidimensional representation of music, of a sound configuration. So that would be the staff, what you read in page one through three of the score, right? But the thing is that you have something else, and that other aspect is the instructions. So for instance, in terms of instructions, it refers to a certain method of producing the sound, which the result you only know when you go through the process of doing it. It’s not descriptive because sounds are not there. It’s the difference between that part of the score and the part which is specifically notated. So you have time segments and you have the arrows and numbers for each event. For interpretation, the first thing you need to do is to know how these two aspects of notation come together. So you have like two poles. You have the descriptive on one side and the prescriptive on the other side. So what is important for a performer is being able to discern between one and the other. Or maybe how one affects the other. Because in every, every experimental score, you have both all the time. All the time you have a graphical representation of the sound, and a prescriptive aspect which tells you what to do to produce the content, the sound, the actual sound of music. And each experimental score, not necessarily experimental - every score has that, but in the case of experimental music, that process in which you discern how they affect each other is very important because that gives you a specific space to work. You know, it’s like an area of work. It’s a methodological field, if you want to call it that. So, for instance, if we take the sound of event number two, we have the arrows, we know that the sound should start at 01’41” and should stop at 02’06”. In the prescriptive area of the score, you can read that all sounds are played rather soft. It says also that the time arrows indicate the beginning, the end, and the duration of a sound event. And every note is held ‘til the end of each event, and only then the strings are damped carefully. So, when you put that part of the notation, and you establish a link between that and what is actually written in the score, you have a methodological field. So you know how to produce a sound, you know how to read the score, and it gives shape to the sound event itself, the prescriptive aspect of the score. So there’s a tension between both, because there you have the space in which you have to create in the case of this specific score and a specific articulation of the sounds, or if you want to call it, their sequence. So you can determine what is indeterminate, which is in this case how every note is related to a certain chord, or how the sequence is made during a specific sound event. So that’s the process of determining what is indeterminate in the score. And you do that, when you put that, that elaboration process, in contrast or in relation to what is actually already in the descriptive aspect of the score. So the tension between these two, which is a kind of dialectical tension, you have to determine that, you have to be aware of that, and it’s different in each score. So that’s the first step for me to interpret a piece. You have to know which is which. The problem is that if you already have an idea in mind, you read every prescription, every aspect of the notation, as descriptive. It’s like a mold you put on top of the score. You already know what to do before doing it. It’s contrary, it’s at odds with what should be an experimental interpretation process in these kinds of scores. So turning everything that is prescriptive to descriptive, you change the nature of the notation itself. So that’s why it’s important always being able to discuss what the performers do with the score. Because everyone has a different take on notation. The thing is that when you transform everything that’s prescriptive into something that is descriptive, you are in the terrain or the territory of mainstream or cultural conventions of experimental music. Which is, knowing what to do before doing it.

KP: Yeah, style, right?

CA: Yeah, style, style. Experimental music in that regard, it’s not a style. It’s not that you don’t have conventions you have to follow, the thing is that those conventions point to process. Not to a sound result prior to the fact, you know? So that’s kind of the big difference between all the forms of contemporary music. You find these same problems in every score ever written. You always have to determine the relation between prescription and description, all the time. The thing is that if you rely only on the descriptive aspect, if you’re playing Bach for instance, that means you have an already solved legibility system. You have already a system, that is a way of reading the score that is already settled. It’s already devised and designed and you just take it then you do it. In that aspect, you are transforming everything that is prescriptive to descriptive.

KP: I’m gonna have to digest that a little bit... what were some of the decisions that you went through for Insinuations?

CA: Yeah, well...What is important with the score is that you have to know, you have to discover some of the things you already do. For example, in terms of playing, of performing, you need to know how long can you sustain certain notes, how to damp them according to what you have already done in the time segment, for instance. So, you need an essential knowledge of the guitar, of the way you play. So you can do, or you can experiment, or you can try different things for each time segment. Also that means that you have to have certain technical skills. And then what you do then, so you know already the prescriptive aspects and the descriptive and you link that with your technical knowledge. And then you try several things.

KP: Did you try a few things that you didn’t like before you landed on what you ended up releasing?

CA: Well, yes and no. Every score is not indeterminate in the same way. So you have more fixed things sometimes and sometimes you have to create everything. In this case, everything is pretty much set. The only thing that is not set is the relation between one tone or sound with another in the same sound event. So there you need to try different things, for instance, I don’t know, play the first note a little shorter, the next one a little louder, or faster, you shorten the time between one and the next. And, well, methods of musical analysis there are very handy. I tend to use James Tenney’s method, which is described in his master’s degree thesis, Meta + Hodos. Then you kind of have a vocabulary to talk and think about music, especially with music that doesn’t involve necessarily tones or frequencies. Most of the methodological analysis… [laughs] methods are based on frequencies, so how do you analyze silence, for instance. So I used that one to devise this and what you have here also is a tension between silence and sound events. It doesn’t mean that during the silence there’s no sound event. There are. But they are not determined by me. The only thing that’s determined are the sound events, the spaces in which I play. The rest of the time, I just listen. Which is a kind of determination… it’s a way of determining what’s indeterminate in that it’s not pre-shaped, it’s contingent. To the actuality of the piece. So every time you listen to this piece, it’s different if you have your window open, or if you are in bar, or in subway, or at home, or if you listen to it in the morning. What is already settled, what is already determined by me in the recording can change contingently.

KP: I do most of my listening on headphones so what I heard, or at least I think I heard, was the amplifier.

CA: [laughs] yeah, all the time. That’s there all the time.

KP: Kind of what I mentioned on Signal with my interpretation at the end of it, of your performance is that I interpret it almost as a continuation of sounding into silence. So, you know, these beautiful undulations from what you’re playing that go into the silence or amplifier undulations and then it almost kind of teases you - once again back to the arrows - kind of going into the beginning and the end of the piece, I feel like it asks you to listen to unheard undulations on either side of the piece almost, or silence on either side. Which, you know, is completely… if I want to interpret it that way, it would no longer to make sense - on top of actually not listening to the instructions - to have my own sounding event where those silences are.

CA: Well, that’s experimental music. What is very important with this kind of music is that even if you still have the figure of, the character of the performer, the composer, the listener, in traditional music they tend to be lineal, you have a straight relation, between one and the next. Every step of this sequence between composer, performer, and listener, it’s determined in a certain way. So they depend on each other. It’s very difficult for a listener to engage with the score independently of the performance. It’s difficult in traditional music. If you have musical training, maybe you can read the Ninth Symphony of Beethoven without listening to it, or without playing maybe. How do you do that with a score like 4’33”? It’s difficult to know, because every time you do it, it’s going to change. So that points to something that is quite important in experimental music, that every part, every element of this sequence is independent of each other. Basically what this means is that you can do whatever you want with what you’re listening to. It’s up to you to give shape to what you’re listening to. You are in the process of listening, which is an intentional thing, and that’s different with hearing. Listening, it’s voluntary, it’s something intentional. Hearing is not. We hear all the time. But our conscious process of listening determines what we want to give sense to. So in that regard performing and listening are different things. You can do whatever you want with what I did.

KP: And I guess just since you mentioned the chain, did you communicate with Radu at all on this?

CA: No. It’s not necessary, I think. That’s one of the things, that it’s always kind of tricky in terms of interpretation. Because some composers want something very specific out of their scores, but they don’t write it like they want something very specific. They want you to do a certain process, but there’s always a danger if the process... the complete sequence that entails process, it’s undetermined by him. Like the prescriptive aspect. If you only say what you have to do to produce sound and you don’t notate the sound itself, you can have basically whatever you want. So sometimes some composers they want something to be experimental in process, but actually they want something very specific, so they’re focusing more on the result than the process itself. And that’s kind of normal, because if you think that there’s a continuous tension between prescription and description, you always have indeterminate elements in a very direct relation with something that is already determined. The only way you can have indeterminate notation is if you have already there something that is already determined.

KP: mmm lemme think about that… [laughs]

CA: [laughs] yeah, for instance, if you take this piece, what is already determined are the frequencies, the notes, their position on the guitar, which are standard. Every guitar student can read these chords. What is prescriptive is that you have to dampen the strings, and you have to determine the sequence and the relation between one note and the next, etc. If Radu wanted something specific, very very specific, he would have written the rhythm. So if I do a version of this, and he doesn’t like it because my version doesn’t really correspond to what he meant, he should have written more descriptively. And since we are reading a score, which is an object, and an object with certain characteristics, which is its notation, notation is always in some regard, in some way, already determined, it’s descriptive. Because you have already kind of a sound configuration in front of you, it’s bidimensional, it represents something, a way of constructed sound or a certain sequence or a superposition of two kind of materials. And if you think of a certain score, any indeterminate score, you have both elements. The thing is that sometimes you have more indeterminate elements in respect to determined elements and sometimes you have the other situation. So that gives you space, that’s why I was talking about the methodological field. Because when you determine that, when you know that, when you’re aware of that, you know more or less what to do and what not to do. Because with notation you have two - well, you have more - but for me what are important are two visions, two perspectives. In one, you have a prompt for action, so something that entails a certain action and that’s it. And on the other side you have a way of thinking about notation where instead of telling you what to do, notation tells you what not to do. It’s a very different approach to notation. So if notation is only a prompt for action, it’s kind of complicated to really understand descriptive notation, because descriptive notation acts like a limit. You cannot go beyond that, because it’s something that is already determined by the composer. And the actions are kind of the content of that something that is already designed. But if you think of prescriptive notation as something that’s a limit in itself, so it points to certain things you don’t have to do, what comes as content can take different shapes. Very different shapes. It acts negatively in terms of it’s always limiting itself as to what you can do. For example, if you have here, ‘all sounds are played rather soft’ first of all it’s difficult to know what soft is. What is soft? It means that I have to record it soft? I have to record it super loud and then I have to do a balance in which every sound is at a minimum of intensity? Or you should play it soft? It tells different things. So you have to devise what to do in terms of your own experience with the piece. So, tensions what you already know, with this field in which you have also to decide whether this is only a prompt for action or its a limit in terms of what not to do... I know it sounds a little complicated...

KP: yeah, so I guess so soft is an indeterminate word, telling you not to…

CA: well, I mean, soft is opposed to loud, but that doesn’t mean that you don’t have different shades of soft.

KP: yeah, I noticed with the next direction, the damping, that you switched that up section to section too. Like some are super pronounced damping and some are almost silent, I don’t hear the action at all. So I guess changing those small indeterminacies even throughout the performance...

CA: yeah, well, the thing is that it’s contingent. You are playing the piece so sometimes you want to do something and it doesn’t come out how you want and you have to take a last minute decision and you just damp the strings. It’s not super soft, it’s not super subtle. You have that too. And I decided to keep those. Because I think otherwise, that’s kind of a criteria… I can have a certain criteria in this methodological field in which I say, ‘OK if I want to have a super soft damping the last note has to be played always in the middle of the measure so I can have time for the sound to decay and then to damp it without hearing it.’ But in that case, every sound event has the same shape, you know, because every time the last note is going to be in the middle and you have there like a rhythmical pattern.

KP: Yeah, so now that you actually mention it, I noticed on the hard damped ones, the last note was pushed towards the end a little bit. I think the first few, these were relatively even spaced soundings within each measure and I started to notice that they took different shapes, pushed towards the beginning or pushed towards the end...

CA: yeah, different ways of approaching the same structure. That’s a decision you have to take in regard to the prescriptive instruction which says, time arrows indicate beginning, the end, and the duration of the sound event, and every note is held til the end of each event and only then the strings are damped carefully. Carefully is also a very indeterminate word because it’s… obviously easier to be careful if the last note is in the middle of the measure than if it’s in the last second of the measure. That doesn’t mean it’s not careful. It’s just careful in relation to what I did.

KP: Yeah, as careful as can be in those conditions.

CA: Exactly. But you can also interpret that instruction as a limit. So what not to do. And what not to do would be maybe to damp the strings as I did in some sound events. In that way the prescriptive notation tells you what not to do. The thing is that you can predetermine that. Like I can say, ‘OK I want all the damping to be super careful and inaudible so supersilent.’ So that determination, that decision, that criteria would shape every sound event. They would resemble one another. Which is not a problem. It’s OK if you do that. But for me these pieces, and we talked about this during the interview, they are supposed to produce problems which you have to solve and you have to test and you have to approach that boundary in which you are exceeding the score itself. You’re doing something else, maybe. Only then you really test the possibilities of that methodological field.

KP: What kind of decisions were you making around the shape of a certain segment? Just previous playthroughs and what you enjoyed hearing with that material?

CA: Yeah, yeah, for sure.

KP: And then of course a little, you know, you’re out there shredding Guns N’ Roses [laughs] so I’m sure it’s not too much performative difficulty but I’m sure there’s some of that too?

CA: [laughs] Well, it is difficult to play these pieces because you have to be very delicate and at the same time everything must be audible. Playing soft is complicated because you have to be able to have a certain technique that allows you to project sound. I mean the vibrations of the strings have to be super accurate.

KP: This is more of a technical question but I’m guessing all the sharps, flats, superscripts, subscripts make it more specific and harder...

CA: yeah. Every time you have a roman numeral and you have there the subscript, you have for instance in the second sound event, you have sixth string, which is the roman numeral, and you have number three. Number three is the third harmonic of that string, so the harmonic you do in the seventh fret...

KP: and then that little sheer symbol also indicates harmonics?

CA: I don’t know how it’s called in english but that means that you have to play, in the first note, that b, it says that it’s not sharp and it’s not flat. It’s something quite specific.

KP: Sorry just going through some technical stuff but the open circles above notes?

CA: Open string. Zero usually is open string. The way of notating these kind of sounds is actually very difficult. There are very different systems everywhere. So I already… also that is important because the way you determine or you understand prescriptive notation and descriptive notation also has a direct relation with context. So what’s context for me in this case? I know already how Radu notates harmonics. I have a previous knowledge of it. So that context allows me to have an understanding of how I can read the score. Especially what is descriptive.

KP: One of the other things I was interested in, just extramusically, I saw that it was in some other people’s repertoire but couldn’t find a recording. I’m assuming you didn’t listen to a recording before this?

CA: [shakes head]

KP: yeah

CA: no. I usually don’t do that. Some impressions are very very powerful. If you hear the rendition of someone else’s of a piece you are going to play, it can really shape the way you approach the score. So I try to avoid that. Like I recorded Michael Pisaro’s mind is moving IX and I knew, well, Dennis Sorokin sent me his recording a few years ago. I heard it then, then when I wanted to play the piece I avoided that recording. But after that I listened to that recording to compare it to mine and it’s super different.

KP: Yeah, so it (Insinuations) is in Dennis Sorokin’s repertoire.

CA: With Dennis, we’ve talked a little bit about this and we have very different approaches towards scores. I have the impression that he really cares about what the composer says about the performance. I have that impression. Maybe I’m wrong, but that’s the impression I have. Well, you have to devise a way of approaching scores. I have mine and he has his and I don’t say this just to be a relativistic person but I have a set of skills developed through different things, a PhD for instance or my classical formation which points to a very singular way of approaching scores. He has his as well. So what you hear in both the realizations are those differences. Also with electric guitar repertoire… well, in classical guitar, to have very beautiful tone is very important. Actually it’s like an archetype, of what should be a classical performance. It’s very wrong to have like a very ugly sound. Because people would say that you cannot play or that your technique is awful. Did this guy go to the conservatory at all? Or did he study? You can start asking questions because there’s a way of consuming that music where its supposed to have a very beautiful tone. What the electric guitars allow me to do is allow me to play super ugly tones. I don’t mean that my sound is ugly. [laughs] I mean I use my classical guitar technique but I know the instrument will behave in a very different way. The things I take from my classical training is that i have to be super precise. Like when you play harmonics, especially the high frequency ones, you can hear both the attack and the note itself. So that I’m very careful about. I really want to have a very pure sound, but at the same time I don’t want the attack to be super present. That kind of harsh noise [makes pfft sound]. I don’t like that, so I take that. But the steel strings, they behave in a very different way. So what I did, and I did that especially with the Sugimoto piece I just recorded, I wanted the sound to be super sharp. Because I wanted to have the maximum effect of high frequency notes there, present, to be heard. So I crank up the amp. I put a little gain on it. And I did that, and for me it works. Maybe some years from now I’ll do something completely different, but I wanted to try something that is kind of different from the things I’ve already done. I did the same thing with the Pisaro piece and there, every time I put the ebow on the strings I got a very ugly sound. It’s kind of harsh and you hear every vibration of the string. At some point I said, ‘OK I’m going to do this again because it’s not in the style,’ etc. and then I said, ‘well that’s nonsense, I just keep it that way, I played it that way,’ and it gives a very special character to the music. In that regard I can say that it’s really my version of it. I don’t know if someone else is going to play like this kind of distorted sound of the ebow and everything. Maybe in the wandelweiser assumed aesthetic they would think that maybe you have to have like super crystalline and pure sounds and ebow has to be like sine tone and super clean, etc. I didn’t want to do that. I was listening a lot of Guns N’ Roses and Metallica and everything...

KP: [laughs]

CA: and then you have it. There you go. For me what is important is that performance has to have a relation with its entourage, its ambience, what he’s listening to in that specific time. Because it’s important. It’s part of a dynamic relation with reality. And if you assume that music is part of reality, well, it has to be shaped by it.

KP: Do you think the - because you were talking about the acoustic and electric - what do you think the electric guitar brings to this piece, or what makes it inappropriate for acoustic other than the direction that it is for electric?

CA: Well, the electric guitar, what is great about it, is that you don’t need a microphone to record it. That I love. Right now, it’s very difficult for me to record with microphones because it’s super noisy everywhere. People are at home. Well, they’re living there… living and making noise, they go side by side. I can plug straight to the amp, to my interface, that’s great. I love the sound also because I think it has a very peculiar presence, the guitar I have, which I’ve been modifying for over a year now. I tried this one with classical guitar at some point, just to kind of feel how it sounds and it’s a different thing. The sound is completely different. With the electric guitar, the sustain can be a little longer sometimes, it depends on the recording, of course. Every time I pick up my classical guitar, I have my classical guitar sound, which is already known to me and it’s kind of difficult to change. I’m very used to playing a certain way with that instrument and I know the techniques and I know its own kind of language, you know. With electric guitar, even if I played for a long time many years ago, now I’m kind of rediscovering its possibilities, so I’m trying different things, seeing how it goes. At first I tried to emulate the classical guitar sound. I would choose all the time the neck bridge... the neck pickup, like moving it a little, doing some eq with the amplifier, not doing any gain, stuff like that. And then I said to hell with it, it’s part of the instrument to play with gain and I don’t know, it’s kind of fun to try different things, and you can with this kind of music. You can do it. It’s not a problem I think. Maybe it is, I don’t know. But for me it’s not a problem.

KP: Yeah, you’re still sticking to what’s determined [laughs]

CA: [laughs] well, that’s kind of the main point for me right now. Like you have a tension between what you know and what you might know in the future and it has a relation to your past because the things you already know they are already inside of you, they are part of your dialect. And then you encounter new music, you encounter new pieces, and there’s a dialectical relation between what you know and what you are knowing, in the present. And that also points to a way to reformulate the things you already know, because you cannot apply what you know like a mold. I think it’s important for musicians to be open to contingency. Especially because sound… you produce only sound when you do that, when you encounter, in the case of a performer of course, you produce sound, musical sound, when you encounter pieces, when you play music. Otherwise it’s just in your memory and you can draw from that of course. But there’s an aspect of musicmaking in that it’s very actual and it’s very present and it’s being there, in time. It’s made of time, actually. So it’s quite fragile and it changes and the way you remember the things you did it’s different how they sound. It happens to me all the time when I try to forget what I’ve done and I listen to that again [laughs] and I’m surprised, I surprise myself, ‘Wow, what did I do there’ or whatever and it’s fun in that way. I try to maintain that relation with the things I’ve done. I try to learn from them. I’m shaped by them of course. But I try to stay open to something that is present. So that’s why I don’t take my classical technique and do these pieces. Like a transliteration of a certain area to another, like an extrapolation of ideas, but try to see how it goes. Kind of explore the instrument as well.

KP: Just interested how long do you usually spend working through a piece before you might present it, like how long did you spend with Insinuations?

CA: Well, it depends on the piece. What I’m doing right now is play and record, play and record at the same time. I don’t do demos or stuff like that. I tried the piece a few times without recording, just a few things just to be sure to have what I want in the first take, not to do millions of takes. And then I just listened to it. What I’m trying also to do because of the pandemic is that... recording it’s like a photograph, it captures only what is happening in that precise minute. It takes precedence in relation to the future of course because it’s something past, it’s recorded, and you have access to it but it’s determined by its specific moment. So if I hate my recordings, I don’t know, if I listen to this piece again in ten years and say, ‘This is complete crap and I don’t know how I did this and why I did this,’ it’s not really a problem. Because I can do the piece again. And I really don’t care about… I care in terms of the things that I can learn from it, but I’m not looking for the definitive version of Insinuations, which for me is a foolish enterprise. Well, it’s very embedded in the classical music culture, to have like the authenticity of the version that might be used as a reference for the future...

KP: yeah, we talked a bit about this, that’s why I wanted to ask if you had talked with Radu at all or listened to any recordings...

CA: no, but I sent it to him...

KP: you don’t have to share, but if you are willing to share…

CA: oh, he loved it. He was very supportive of the thing I did and everything. He was kind of amazed by how much his writing has changed over the years.

KP: Yeah, this is an almost twenty-year old piece now.

CA: Yeah, of course, I’d be amazed if he was still writing like he did thirty years ago. Some people do that. It’s not a problem. But for him, I don’t know, knowing him I think that would be odd. And it’s the same with Michael. I love the scores he produces, Michael. They are always super fun to play. Plenty of things to think about. I always feel like it’s in a very specific limit between like classical music, very descriptive notation and something that is quite prescriptive actually, and I find that very very interesting about him. He makes now like loud music and I don’t know if he cares but I would guess that he doesn’t really really really care if it’s a little loud or super soft like, I don’t know, he just does what he does and that’s it and I really like that about him. I had really really fun playing that piece, mind is moving [IX], it was great playing it. With the stones and the whistling and that was great. It was awful to record but [laughs]... I had to do that like 4AM in the morning. That wasn’t that comfortable, but still, it was great, I had a great time.

KP: nice I’ll have to check it out…

CA: I like that version. I think though it’s a little heavy metal, you know. You can hear a little something there.

KP: Your version?

CA: Yeah, it’s kind of noisy at some points…

There’s a lot to unpack in that conversation but at this time I recognize a couple of big takeaways.

One begins from the observation that some degree of interpretation begins before the performer sees the score. Whether it’s style or assumed aesthetics, beliefs around the involvement of the composer, impressions from previous performances, the personal context the performer brings to the experience, or the concerted subversion of these and other aspects. Variations in approach to these individual aspects of interpretation and performance result in unique combinations - performance practices are unique. When paired with scores containing greater degrees of indeterminacy, to paraphrase Cristián, the differences you hear between interpretations are the performers. There’s a metaphysical question of where music might come from. The composer? The score? The performer? The listener? As with most hypotheticals of extremes, the real answer is somewhere in between, in part made clear here by what performers bring to the realization of the music. It speaks against the common bias that performers are trained monkeys. And practically suggests that we remain aware of how we talk and write about composed experimental music. From a popular music writing perspective, it’s quite easy to find reviews discussing composers and their compositions at length - sometimes eschewing performers as if to imply the composer(s) realized the music on the recording (when they are not the same person(s)). It’s a misrepresented reality that’s negligent of the work performers do. Though the context around interpretations are not always available, I think performance practices require a greater generosity than they’re often given. Does my own writing reflect this? I’m always open to feedback on the matter.

The second is that there’s always tension, even within satisfactory interpretations. Beyond perhaps giving too little weight to some prescriptive aspects of the score, the way I thought to demonstrate certain relationships between silence and sound perhaps diluted and homogenized those same relationships I desired to accentuate. In Cristián’s case, he compromised the carefulness of some dampings to allow greater variability of shape within sounding events. There is a tension between the descriptive and prescriptive aspects of the score and it remains even when the thresholds of their overlapping conditions are met - the choices that you make to better satisfy one aspect might make another less satisfactory. It always allows another way to realize the music, within itself, beyond environmental or contextual contingencies. It is quite literally what makes composed experimental music experimental - discovering the possible results in a set of conditions through varied iteration.

I encourage readers to think about what they brought to their interpretations, what aspects they felt the need to better satisfy, and how those choices affected other aspects.

When reaching out to Radu about permission to copy the score in the newsletter, I asked some similar questions in our email exchanges to get a sense of his perspective.

Keith Prosk: I’m interested to know what you might expect specifically from performances of the score. If there are areas in which you’d like to see performers take a little liberty, or areas that you want them to stick close to. Really to see if your gradient or field of expected interpretations aligns with where Cristián believes it is.

Radu Malfatti: Of course this is a very interesting question and my personal opinion doesn't correspond to all my colleagues (which is a good sign). The thing is that I usually work only with people who know me and know - more or less - what I want, so I don't have to explain a lot before hand. This is true for rehearsals as well. Liberty yes and no - to a certain extent I want it, but in other realms I don't. The way Cristián played my piece is ideal, absolutely wonderful, and exactly what I wanted or had in mind. And I even didn't have to talk to him a lot about it, he just KNEW it, felt it, whatever.

In my latest piece, which is called otonokage, there is a lot of free interpretation possible and asked for. There are only lines and dots in the score. Very long lines, short lines and little dots, that all tell the performer the length of the sounds, but no pitch.

And again: I was recording it with people knowing me and my likings and dislikings...

KP: I know this was written some time ago and the symbology you use and the reasons behind it might have changed, but would you be willing to talk about your intentions in using the arrows?

RM: As to the arrows in my older pieces: they indicate when a sound starts and when it ends. Of course you could write it in a different way, but what I had in mind was the picture of a sound coming out of the silence and going back into it…

KP: I’m aware this is dedicated to Michael Pisaro, who might be a little more associated with the electric guitar than acoustic, but is there perhaps something possible with the electric guitar that would not be possible with acoustic in the context of this score (besides sustain)?

RM: Well, besides the fact that they do sound differently there was no real reason to use electric instead of acoustic guitar. It was only because Cristián asked me if he could do it, I was of course very pleased about the idea. The sustained sounds are never that long that it would make a real difference; if I want a real long note or sound I would like to use an e-bow, but within seconds there is no real difference in sustaining, besides the fact that it actually sounds different and I like both sounds.

Obviously, if I would be interested in heavy metal or the likes, then you have all the possibilities of distortions of the sounds, which doesn't interest me, needless to say…

KP: Cristián and I talked a bit about different approaches from interpreters/performers, and a bit about how involved they are with the composer. Are there some practices in performance approach you’re particularly fond of? Whether or not you expect it, do you prefer working with performers in interpretation? or letting someone figure it out on their own?

RM: This reaches out to the earlier question or answer about performing and interpretation. As I said before, I'm not really fond of certain approaches to or for the performer, I'm more interested in working with people who know my music or understand more or less what I want. It is very difficult to work with people who don't understand or even are not willing to understand what I'm trying to say or do. I could tell you many stories about situations where I was confronted with musicians facing this problem, including a woman who really wanted to play the piece and couldn't no matter how much she tried - she was (or is) a wonderful player but she just couldn't manage it, even though she wanted it and tried very hard - and on the other hand a bass player who got quite upset and he shouted at a certain moment: "I didn't study music for six years in order to play this crap!" which was quite funny, I think.

So, you see that this is quite complex in a way. I want them to figure it out, yes, but only to a certain extent. Where is the border? where is the limit? can it be discussed or just felt?

As I said, I didn't discuss it very much - hardly at all - with Cristián and he did it straight away, felt it straight away.

While not overly rigorous, I think it’s pretty rad to see some perspectives of composer, performer, and listener together. The seed of wanting to present alternative notation in this newsletter originally came from the thought that pictures are cool. But what’s developed along the way is a deeper understanding and appreciation of the processes behind the sound that translates to a deeper understanding and appreciation of the sound itself, from a perspective I never got from listening to recordings and reading liner notes. Cristián’s hands-on exercise of having me interpret the notation before hearing the sound only amplified it. Going forward, I think I’ll try to do the same for the scores presented here, and I encourage you to do so too. Cristián’s description of the lineal dependency of listener upon performer upon composer has some truth - that interpretation comes from practice - but I suspect several readers of the newsletter are up for the challenge, and I know I am...

annotations

annotations is a recurring feature sampling non-traditional notation in the spirit of John Cage & Alison Knowles’ Notations and Theresa Sauer’s Notations 21. As a non-musician illiterate in traditional notation, I believe alternative notation can offer intuitive pathways to enriching interpretations of the sound it symbolizes and, even better, sound in general. For many listeners, music is more often approached through performances and recordings, rather than through compositional practices; these scores might offer additional information, hence the name, annotations.

Other resources exploring alternative notation include: Carl Bergstroem-Nielsen’s IM-OS journal; Christopher Williams’ Tactile Paths; and various writings of Daniel Barbiero, including Graphic Scores & Musical Post-Literacy and the liner notes for In/Completion.

All scores copied in this newsletter are done so with permission of the composer for the purpose of this newsletter only, and are not to be further copied without their permission. If you are a composer utilizing non-traditional notation and are interested in featuring your work in this newsletter, please reach out to harmonicseries21@gmail.com for permissions and purchasing of your scores; if you know a composer that might be interested, please share this call.

Christoph Herndler - vom Festen, das Weiche (2006/2007)

The notes for interpretation can be found here. Two performances can be found here. And additional context by way of its three-dimensional representation at the Anton Bruckner Privatuniversität in Linz can be found here. For those in the Berlin area, Zinc & Copper (Robin Hayward, Hilary Jeffery, Elena Kakaliagou) will perform it August 3 at KM28.

Christoph Herndler is a composer whose work focuses on graphic notation and intermedia scores that can often be as fluidly realized in the visual and plastic arts as the sonic. I recommend exploring his site, which features many graphic scores with brief explanations, full notes, and recorded performances accompanying several of them. And I encourage readers to explore the notes and the objects associated with the scores when available, to think about what the nuanced spatial representation and tangibility of these scores makes possible lest, as Cristoph cautioned in our communication, “one gets lost only in the exotic look of it.”

vom Festen, das Weiche is a 2006/2007 composition for open instrumentation. While the process of interpretation and realization is quite involved, the structures and sounds are quite open. Variable rotations and arrangements of the quadrilaterals yield variable sequences of segment length and location along the squares which are used to determine select aspects of form, structure, and sound. Each player selects their own material, is a soloist, and can start staggered and play asynchronously.

Its arrangements include all possible variations for placing a quadrilateral’s vertices at three dividing points of a line; it is a two-dimensional representation of a kind of three-dimensional space fully fleshed out. A player may explore this space in similar ways to how they might explore behaviors of sound in a performance space. Its spatial or dimensional representation might encourage the player to think in a kind of tonal space like that in just intonation, perhaps complimenting it. And, as mentioned in the interpretation of its object, it represents nuanced spatial relationships between sounding and silence in its positive and negative space. vom Festen das Weiche engages its interpreters in the physicality, tangibility, and sensuality of sound material.

reviews

While reviews here can be about anything they are most often about recordings of sound. For some interesting perspectives on this topic, Frantz Loriot’s Recordedness is an interview-based project exploring the nature of recordings.

Romy Caen, Nick Ashwood and Jim Denley - Between Back and Foreground (caterpillar, 2021)

Romy Caen (harmonium, synthesizer, percussion), Nick Ashwood (acoustic guitar), and Jim Denley (winds) play an ecological set in which they might communicate with the contingent sounds of the performance environment as much as they do with each other on the 54’ Between Back and Foreground.

While some silences at the beginnings and ends of tracks allow airplane, motor traffic, and conversation to sound unaccompanied, the post-Cagean strategy that often separates these contingent sounds and those from traditional instruments is not so present here. Rather they play together. And together create a musical environment reflecting the bustling pulse of lived-in spaces. The traditional instrumental soundings are not so acousmatic in the sense their sources among the performers and their respective tools are difficult to place, but they do blur with the environmental sounds. Is the creaking the manual pump of the harmonium or some chair in the audience? Its squeak a birdsong? Its rattle an ice machine? Is that woosh from an open door or the lungs of an instrument or instrumentalist? The pop of an open bottle might be a flute pop if not for the fall and roll of the cap. And a certain buzz might be a vibrating phone if it was not so conspicuously continuous, perhaps string noise. Embedded in this organically percussive playing is longer strings of repeated beats. Key clicks and pops. Tapping. Pumping and circular brushing. Which appears to link the regular yet wavering pulses of harmonic beating patterns - intermittently from each performer, rarely if at all at once - to the less patterned pulses of the environmental sounds. So, a music of many pulses in many ways. The interconnectedness of which still effectively encourages that post-Cagean notion to hear the music in ‘non-musical’ sounds, not just framed separately as silence or the lack of it but as coincident equitable partners in performance.

eventless plot - anisixia (edition wandelweiser, 2021)

chris cundy (bass clarinet), eva matsigou (flute), and nefeli sani (piano) join aris giatas (analog synth), vasilis liolios (psaltery, ebow), and yiannis tsirikoglou (max/msp) to perform the ruminative cyclically progressive eventless plot composition anisixia on a single 37’ track.

The keys attacked tenderly yet with gravity, fractured melancholy piano melodies fracture swells from the rest, their blushing domes sometimes radiating fluttering pulses of harmonic beatings. Their arcs so unified as to fill space reciprocatively and harmoniously, the individual identities of ebow, synth, or other electronics initially obscured save for some signal beeps or conspicuous reverb. A hammered one note repeats alone. After which instrumental relationships stagger and change a little. And this occurs a few times, measuredly. The piano gradually exiting, its melodies replaced with those from winds and its structural place with static hiss, mellifluousness with a little more dissonance, distortion, and vibrato. But after some time, the piano returns and appears to coexist with the hiss and other things, and the ensemble returns towards the gentle intimacy of the beginning with an acknowledgment of what came since. While the notes provide no context for it, I imagine some psychodrama of tension and intimacy, in which instrumental characters dialogue as if in some tragedy, not unlike Sarah Hennies’ Reservoir pieces or The Reinvention of Romance.

https://www.wandelweiser.de/_e-w-records/_ewr-catalogue/ewr2105.html

eva-maria houben - 3 trios (edition wandelweiser, 2021)

carson cooman performs three soft sidelong eva-maria houben compositions for solo organ on 3 trios.

The pacing is calm; the attack, decay, and shape of sounds quite soft - even corporeal low end rumblings assume a gossamer character; the duration of sounds is somewhat sustained; the volume is quiet; and the space is distant and open. The music appears to play in threes: three pieces for trio; three pieces for two keyboards and a pedal; each piece exploring overlapping relationships of three melodic lines or three-tone chords. Some of these overlapping relationships seem cells contained unto themselves, a plaited chorus divided in stanzas, their voices reduced to silence before beginning another progression, and some seem to leapfrog each other, the last remaining tone of a melody or chord the beginning of the next, sometimes separated by silences. But the silences are structured in such a way to indicate the presence of the soundings surrounding them, as if the pause of lines within overlapping segments happened to occur all at once. And among the mutable sequences of stacked tones, new pulses from their harmonic interactions come to light, the thrum, throb, and hum of organ quickening, slowing, stabilizing and sometimes seemingly resonating into the silence, the melodies and chords alive despite their quiet. The timbres and ambience here don’t obscure the organ’s ritual character - though its muted and measured aesthetics are more akin to a kind of quietism or asceticism than more brazen denominations - and the distance perceived in the recording accentuates it, as if something just beyond human - edificial, angelic, a dream.

https://www.wandelweiser.de/_e-w-records/_ewr-catalogue/ewr2108.html

Charlotte Hug | Thomas Rohrer | Philip Somervell - F U O G N (QTV Label, 2021)

Charlotte Hug, Thomas Rohrer, and Philip Somervell play two pulsing, breathing, subtle, sidelong environments for viola and voice, rabeca and soprano saxophone, and pipe organ on the 44’ F U O G N.

The trio maintains a relatively tight dynamic range and is never silent all at once, moving instead through subtle shifts in color and rolling accumulations of textures and the variable densities of their pulses, cloud formation ballooning and wisping. Furthering the characterization of this sound as some protean mass in flux, these textures blend: the rougher rabeca with noisy viola; saxophone air notes like some unsounded air pumped through pipe organ; viola harmonics like flute; rabeca attack like giddy hammered organ; whistling ululations and vocal hooting with the throb of the organ; soprano microtonal chirpings like those ululations; the pop of saliva in the sax with vocal spats; undulating dynamics mimicking the beating resonance of organ. The organ is everpresent, the strings and other winds at times peeling away to reveal a pulse as if you had been traversing on or in some behemoth without having known it. In this textural, harmonic environment, sometimes an emotive half-melody emerges in moody impressionistic movements.

anne-f jacques - poudrerie (winds measure recordings, 2021)

anne-f jacques amplifies and records handmade devices and contraptions across four tracks on the 25’ poudrerie.

The sounds are from anonymous sources, maybe some metal and wood materials detectable, but they are the sounds of mechanical work. Bustling. Creaking. Carving. Clinking. Chiming. Rolling. Whistling. The frictional clank of cogs acting upon each other, or something like it. All cyclical, sisyphean work. There’s a certain grain in the amplification or recording that lends a decay and ache to it. And likewise a ghostly resonance or reverberation low in the mix that sometimes sighs and wails in human intonation. Little automatons not necessarily in their shape but in the work-weary sounds they emit.

Konus Quartett & Klaus Lang - Drei Allmenden (Cubus Records, 2021)

Konus Quartett and Klaus Lang perform a three-part open composition for four saxophones and harmonium on the single-track, evening-length Drei Allmenden.

While I suspect Drei Allmenden is a Lang composition, it’s unclear. What is clear is a collaborative approach to musicmaking cultivating equitable dynamics between composer and performer, recalling not the means but the ends of compositional processes like Nate Wooley’s Mutual Aid Music or Christopher Williams & Liminar’s On Perpetual (Musical) Peace?, though this has been an integral feature of Lang’s practice for some time. Another familiar feature of Lang’s work is the priority of sound itself, which often results in stunningly beautiful, achingly cathartic progressions in time. Drei Allmenden is no different. The pace, movement, and timbre of saxophones and harmonium remain close, the quintet a unit, a mist-like mass of subtle gradations in density and color, traces of melodies slowly, subtly unveiled in its unfolding. Its three parts appear as aspects of pulse. The first purring with harmonic beatings dancing individually and also together in their interactions; gentle cascades of call patterns from saxophone beating like crepuscular rays shine in the second; and the third accentuating the natural undulations of air in sustain, with shifting colors that could be confused for choral voice.

Konus Quartett on this recording is: Christian Kobi (tenor, soprano); Fabio Oehrli (soprano); Stefan Rolli ( baritone, soprano); and Jonas Tschanz (alto, soprano).

http://www.cubus-records.ch/en/work/lang-konus-allmenden/

Catherine Lamb with Bryan Eubanks & Rebecca Lane - Prisma Interius IV (umland editions, 2021)

Catherine Lamb, Bryan Eubanks, and Rebecca Lane perform the titular Lamb composition with voice, viola, flute, and secondary rainbow synthesizer on the meditative, dimensional 58’ Prisma Interius IV.

Relatively sustained soundings of one or few tones, of various duration, and of changing temporal relationships from each source shift among different overlapping assemblages, sometimes all lines silent at once. Faint resonances between voice, viola, and flute illuminate their shared harmonic spaces and though the origins of beatings might blur in their interdependency the timbres of the source are never obscured. They appear to float in and out of some austere melody. The secondary rainbow synthesizer here is a shimmering celestial chime, mostly pulling birdsong from beyond the performance environment, perhaps playing back some voice. While it appears to follow a similar structure to the other sound sources, its role is mysterious if not to effectively converge physical spaces in some way similar to how performed soundings might converge tonal spaces.

hannes lingens - music for strings (edition wandelweiser, 2021)

The string ensemble CoÔ performs a three-part composition and félicie bazelaire performs two solo compositions for contrabass and cello from hannes lingens that showcase the expressive possibilities of strings on the 54’ music for stings.

triptych is a kind of suprematist suite displaying aspects of the string family in the audible plane. “part 1” reminds me of the work CoÔ did with Bertrand Denzler as presented on Arc, swaths of bowed strings richly layered and separated by silences, each cell progressions of minute variations alternately foregrounding the frictional timbres of the various family members and their individual registers, its rhythm largely determined by the structure. “part 2” might play with the more overtly rhythmic characters of strings, percussive pluckings and muted thumpings, tender bowings that assumes sounds closer to the timbre and pace of breath than strings, and more discrete attacks of scratch and string noise. And “part 3” is the ethereal rhythms of pulse from harmonic beating patterns, hastening and slowing amongst train horns and nosediving airplanes in a bottomless glissando. Similarly “methods & materials” for solo contrabass presents a hefty range of approaches that appear as vignettes separated by silences. Fluttering plucking in a running cadence; tapping various spaces of the body; plucked scales; bowed scales, with gusto; arco melodies with variable shapes as the duration of silences between soundings fluctuates; rich, sonorous, beating bowings. “solo for sting instrument,” performed here on cello, is a little more singular, composed some years before the other pieces. Its bowing walks the threshold between sounding and silence, producing a sound closer to breath, the cadence of bowings and their returns similar to that of exhalation and inhalation. Perhaps perceivable as a catalog of technique but there is some sense that this is more a celebration of instrument, instrumentalist, and their relationship.

ensemble CoÔ is: bazelaire; patricia bosshard (violin); cyprian busolini (viola); benjamin duboc (contrabass); élodie gaudet (viola); frédéric marty (contrabass); and anaïs moreau (cello).

https://www.wandelweiser.de/_e-w-records/_ewr-catalogue/ewr2101.html

Andrea Massaria - New Needs Need New Techniques (Leo, 2021)

Andrea Massaria performs nine solo pieces inspired by painters Jackson Pollock, Robert Rauschenberg, and Mark Rothko for electric guitar and effects on the 44’ New Needs Need New Techniques.

Visual and aural art might share more similarities than not. The way we talk about timbre resembling color. The character of points and lines or strokes resembling sounding durations, attack, decay. And both are spatial, the visual occupying a space or volume with an implied movement, the aural - beyond the physicality of sound waves - likewise perceived to move up and down in its tonality, forward or inert in its momentum. While the visual can be experienced all at once in a moment, observing it in any detail puts it in time, the eyes moving from one corner of the canvas to the next, interpreting the relationships between the spaces within the piece, not unlike the unfolding narrative of time-based aural art. New Needs Need New Techniques draws attention to the relationship between the visual and aural by contextualizing its sounds in the practices of three painters. The Pollock pieces featuring percussive, punctuating attacks, dripping reverb, soaring tones like the broad wave of an arm, sinuous noodling, and dense, active tempos like action painting. The Rauschenberg pieces draw from the Combines that incorporated unpainterly materials, with layered spoken word, radio, and perhaps - I think I hear the click of a stick in “RA1” - preparations overlaying sculptural planes of sounding. And the Rothko pieces simulating colorfield in their longer-duration soundings that foreground texture and pulse within them, sometimes separated by more pronounced silences as if in bars. The range of effects used lends an expanded palette. Not some cute simulacrum but a comparison to familiar sources that asserts performative gesture has real effects on the sound result and the experience of it like visual art is intimately tethered to the physical actions of its artists.

andré o. möller with hans eberhard maldfeld - out of a matrix (partially) (edition wandelweiser, 2021)

hans eberhard mandfeld performs four harmonically rich andré o. möller compositions for solo five-string contrabass with pre-produced playback in just intonation on out of a matrix (partially).

Twenty-second silent tracks separate each piece and additionally ten-second silences occur every 4’15” in the first piece. Otherwise it is all sonorous arco. The notes reveal a lot of information around context, process, intent, and structure, but the apparent sound result is fields of deeply layered bowings emitting beating patterns out of their harmonic interactions. A thorough survey of the harmonic physics at the limit of this instrument. As someone unaware of the intricacies in performative difficulties around the instrument, I might not recognize the playback but rather assume it’s the chordal capabilities of stringed things or double bowing on open strings, such is how the two closely compliment each other, often producing multiphonic stacks of four or more lines. The beatings patterns are diverse, from turning truck motor to singing sirens to skipping throbbings to buzzing tanpura to ethereally smooth pulses that wholly obscure the friction of the strings, as are the textural fields across various registers from which they emerge. This scape of pulse makes possible some particularly cathartic movements, especially when the strings sound like horns, at turns bittersweet or as if urging some call to arms before falling.

https://www.wandelweiser.de/_e-w-records/_ewr-catalogue/ewr2103.html

Phill Niblock - NuDaf (XI Records, 2021)

The single track, hour+ NuDaf is a harmonically deep and rich multitracked arrangement of sustained soundings from bassoonist Dafne Vicente-Sandoval by Phill Niblock.

Quite quickly the piece is a chorus of woodier heralds. Long, longer, and some seemingly endless soundings layered to juxtapose techniques impossible to perform in real-time. Angelic high and rumbling low registers. Distorted train horn and pure clean tone. Something very human that may very well be voice. Many soundings multiphonic, harmonic beatings rising from them. And above this already dynamic strata of primary soundings, their several independently hastening and slowing pulsing harmonics play and fold and synthesize with each other to form new layers of new pulses in the ether. As density and the prominence of beating patterns gradually increase towards the end, the effect is as if an ecstatic pipe organ was laid upon with more than ten fingers.

Weston Olencki - Verd Mont (SUPERPANG, 2021)

Setting aside their usual brass composition and performance, Weston Olencki acclimates to a new home in Vermont by exploring its histories through a Sacred Harp tune and field recordings on the two sidelong tracks of the 38’ Verd Mont.

“Vernon, L.M.” transposes the titular Sacred Harp choral to pump organ, its melody mostly drawn to unmelody in sustained tones that reveal their ecstatic frolicsome throb and pulse and beatings among relict segments of familiar movement, accompanied by a rhythmic scuff like a brushed shoe buff and an industrial churn and scream from a quarry saw. I might discern that the sounds are not wholly unmanipulated, but I cannot identify the various materials involved in their processing indicated in the notes. “witched windows” is fourteen tape loops separated by silence, though anonymous movement from the playback environment or glitched tape artifacts occupy those quiet spaces, the pops, clicks, and whirr of the latter a constant substrate for the warped and cut tunes that consume the bulk of the volume in the loops, stretched Screwesque scratches to bittersweet MBV-like melodies and more carnivalesque fair and pavilion brass band drowning out the sounds of weather, or caverns, or voices, or fauna that might appear faintly.

Given the context in the notes and the potential ecological character of field recordings, I assumed I might hear something of Vermont. Shimmering aspen in the wind, plodding snow fallen from firs, cracking ice on beech bark. Its loam and clay creeped into the cassettes of its exhumed effigies to crackle and click. The percussive colluvium of glacial till mantling the ancient Green Mountains hewn by the Laurentide whose death brought the Abenaki people which this recording acknowledges and to which it donates the proceeds. But while the modern materials of its current inhabitants produce some aspects of the sound, it is disintegrating and decayed and the sound result assumes an anonymous locale, its colonial music possible anywhere in the globalized domain. I think Verd Mont means to show the follies of power exerted on nature, time, silence, each other but whatever the interpretation it navigates the tensions of living in a world we’ve changed with the consciousness to know it.

The Pitch - KM28 (Tripticks Tapes, 2021)

Boris Baltschun (electric pump organ, computer), Koen Nutters (contrabass), Morten J. Olsen (vibraphone, tape delay), and Michael Thieke (clarinet) perform six group compositions with an expanded conscientiousness towards tuning and modular configurations of performers on the harmonically-rich, six-track, 52’ KM28.

KM28 features vibraphone in just intonation and just intonation rearrangements of existing compositions “Frozen Surface” and “Pillars” and, while those two tracks feature the full quartet, the rest are duos and a trio for fresh variety. This development in tuning opens new harmonic spaces for the ensemble to explore and, while The Pitch have always had a keen ear for music of pulse, results in alluring environments teeming with polyrhythmic pulses and their harmonic interactions and sensual textures. “Frozen Just” is a refracting pool of pulse, densely built stacks of sounding emitting diverse waves in their overlapping relationships in space. And “Just Pillars” is stratified columns of undulating drones with tense tonal shifts of great gravity overlain with an ominous lumbering cadence and long decay from vibraphone. The tape delay and sines of the trio are quite subtle and perhaps unheard beyond some electric buzz and the ghostly playback of plucked bass harmonics but are quite evident in their own duo, a chorus of insectoid chirruping reverbed, knocking, whinnying, swarming. Though by no means a silent music, “Clarinet & Vibraphone” accentuates the spectrum of sound and silence, the gradient dynamics of barely-there airy clarinet and the long decay of vibraphone overlapping at various points between their provenances, the siren song multiphonics of the former and longform undulations of the latter together making new waves. And again, on “Vibraphone & Sines,” some ethereal exchange fishtails newly-formed singing sines from the gentle crests and chimes that come from mallet strikes.

Christopher A. Williams & Liminar - On Perpetual (Musical) Peace? (Edition Telemark, 2021)

The ensemble Liminar perform three open, colorful, collaborative compositions catalyzed by Christopher A. Williams, who joins the ensemble on contrabass for the sidelong “Chains and Trios of Trios,” on the six-track, 42’ On Perpetual (Musical) Peace?.

The notes provide a thorough context around the logistics and intentions of these pieces but the core of the project is cultivating an environment in which performers, improvisers express their individuality and composition asks them to explore their limits and perhaps push past them and in so doing establishes equitable power dynamics between composer and performer. This is certainly reflected in the diverse textural palette of every piece. The four brief versions of “A Musik,” for duos, quartet, and octet, evoke the papers the pieces are based upon. Relatively sustained, one tone lines tracing edges; percussive, pointillistic, punctuating patterns the spiral-bound scalloped edges, corrugations, or inked lines on a page. Frictional textures the grain. Dynamics the transparency or size relationships. So on. And they establish the quick clip and judicious spaciousness of the whole project. “Palitos” revels in the timbres of percussionist Bernal Villegas’ extensive stick collection, the whole ensemble playing the room. A bunch falling as if starting a game of pick-up sticks; rubbing, clicking, screeching; the sound of a stick along a fence; swooshing them through the air; dings, chimes, and roulette spins. The dimensionality of the space clear in the recording. “Chains and Trios of Trios” asks players to oppose or adapt previous material. While there are some clearly continued and halted patterns, some exchanges interestingly blur to illuminate the spectral middle, where oppositional actions might appear adaptive and vice versa.

On this recording Liminar is: José Manuel Alcántara (guitar); Darío Bernal Villegas (percussion); Alexander Bruck (viola, viola d’amore); Ramón del Buey (bass clarinet); Carlos Iturralde (requinto, electric guitar, objects); Mónica López Lau (recorders, bird call); Omar López (baritone saxophone); and Natalia Pérez Turner (cello).

https://www.edition-telemark.de/923.07.html

Thank you for reading!

$5 suggested donation | harmonic series will always be free with no tiers or paywalls. This approach is lifted from common practices in experimental music communities of openness, inclusivity, and accessibility in their performances. Similarly it is now lifting the common practice of suggested donations. If you have the means and find yourself spending an hour or more reading an iteration of the newsletter, discovering music you enjoy in the newsletter, dialoguing your interpretation of something with those in the newsletter, or otherwise appreciate the efforts of the newsletter, please consider donating to it. More or less is equally appreciated. Disclaimer: harmonic series LLC is not a non-profit organization, as such donations are not tax-deductible.