1/6

conversation with sound artist Sasu Ripatti; notation from Ryan Packard; reviews

Houston, Texas’ Nameless Sound performance series continues celebrating its 20th anniversary by diving into archives of previously unreleased sound, video, and stories from musicians with deep connections to the series, most recently featuring Pauline Oliveros. Previous profiles include Joe McPhee, Maggie Nichols, and Alvin Fielder.

Potlatch has announced their summer sale. €10/CD; free international shipping; June 18 through July 18. RIYL: Erstwhile Records; wandelweiser; echtzeitmusik; onkyo; free improvisation. Catch ISSUE Project Room’s panel with Pascale Criton, Silvia Tarozzi, and Deborah Walker and interested in their work? Criton might be a perfect companion. Enamoured with everything about Éliane Radigue’s OCCAM Ocean, especially after the recent Sound American issue? Several releases feature the chevaliers, including Frédéric Blondy, Angharad Davies, Robin Hayward, Tarozzi, Dafne Vicente-Sandoval, and Walker. I have never not been amazed with what I’ve heard presented by the label and it’s introduced me to quite a bit of work that has expanded my perceptions around listening. Sales pitch feels weird but I really dig the curation, future releases are funded only from sales, and the label’s a little quiet about it.

I recently stumbled across and have enjoyed perusing through the archives of surround, a dormant journal co-edited by Mark Flaum and Jon Abbey, featuring writings from Michael Pisaro, Taku Unami, Yuko Zama, and many more people working around post-Cagean and related music. I hope you enjoy it too.

harmonic series will always be free but, if you appreciate the efforts of the newsletter, consider donating.

conversations

I interview Sasu Ripatti, a Finnish sound artist with a variety of distinctive projects under different monikers though perhaps best known for his work as Vladislav Delay. Over video chat, we talk about wilderness and silence, frustrations around extramusical trappings and the value of music, hip hop, collaborations, writing, and always changing, challenging, exploring in his practice.

Just this year, Ripatti has released Rakka II and Fun is Not a Straight Line and maintains a Bandcamp subscription through which exclusive tracks are regularly released.

Keith Prosk: Hey! How are you?

Sasu Ripatti: I’m alright. I’m alright. Thanks.

KP: I’m so sorry about the time mix-up. Is it four or five over there?

SR: It’s four now, yeah. Where are you? You’re in states?

KP: Yeah, I’m based in Austin, Texas

SR: What time zone is it?

KP: It is central, so same time zone as Chicago. It’s 8AM right now.

SR: Oh, you’re up early.

KP: Yeah, it’s good. You’re doing alright today though?

SR: Yeah, it’s mother’s day tomorrow. My mom was just visiting and, yeah, just had a little walk and all good. Good. Thank you.

KP: Nice. Are y’all cooking a big meal for mom?

SR: Yeah yeah yeah. I managed. ‘Cause we live not so near, so she came to visit. She’s getting a little bit… she’s like 82 now. It’s good to take a chance whenever there’s a possibility to hang out.

KP: Nice. Well, if it’s alright with you, I kind of wanted to try talking about the Rakka recordings without necessarily talking about the Rakka recordings. So, I guess talking about the arctic environments that I believe kind of inspired the music. I understand you that you take long walks where you’re at, or maybe hikes, and that that kind of inspired the Rakka stuff?

SR: Yeah, I guess you would call it proper hiking. I live around arctic circle, so north-ish, but I go hike in the far north, more in Norway. Sometimes in northern Finland. But it’s more like hardcore, like mountain survival.

KP: Would you be willing to describe some of the experiences that you have and what you take from those experiences back to the studio?

SR: Well, I go there every year and I try to do three, four weeks every year in the summer. Summer is very short so maybe the season is two, three months you can do without snowfall and freezing temperatures. But yeah, it’s all different. It’s a little bit of a lifeline, in a way. Partly it’s a silent retreat. I really believe it’s quite healthy to be on your own and not say a word and not hear a word. Like, where I go it’s off tracks, so it’s real wilderness. I don’t see any people for a week. I usually do seven days at stretch ‘cause I cannot carry heavier loads. But, you know, it’s a… in a way… it’s hard to say… I guess it’s individual. It could be super annoying and life-threatening or boring or whatever for somebody and for me it’s a… yeah, it gets my juices flowing. It took me awhile, but I think it’s at least partially the spaciousness that I find extremely invigorating and inspiring, when you’re like on top, over the treeline. There’s so much space there. I guess, maybe freedom is the right word, I feel. And that spaciousness somehow… it’s quite interesting how, there… it probably has to do something with just repetitive, meditative walking, partially. But I think the atmosphere there in general really somehow triggers something in me which I can’t really reach elsewhere, definitely not in the studio. And it’s remarkable when I’m there how ideas just flow. And some years back I tried semi-seriously to capture those ideas, like writing things down that came up there. ‘Cause it was so stunningly different to everyday life, like what I do in the studio. How much ideas were flowing and how different ideas came up but then when I ended up back in the studio and started reading the notes and stuff, I couldn’t anymore address that same feeling. I believe the terrain has a lot to do with it. That endless space that you have there. There’s no limits there. Around you or above you. And it’s not restrictive in any way except your own maybe mind state. Also, because I did these albums and I’ve been asked these questions so many times I have a little bit lost the romantic feeling. I’m waiting. It’s maybe one month more and then I can go again. So I’d rather do it than talk about it, to be honest. I don’t know if you spend a lot of time in nature, but lots of times people call from like London or New York and you can explain these things and talk about these things but it’s hard to translate the inner space. But for me, I started doing it like ten years ago… But basically seriously I started doing it maybe eight years ago when I decided to take a long break from music. I sold most of the studio gear I had and I decided to just fuck it all. I just really didn’t want to… I guess I hit one of the crises in music, just this music industry and how… just the same shit I’m still struggling with, but it hit me super hard. This whole streaming and all the changes that have happened. I realized I’m really not even remotely inspired to participate in any of it. I decided to take a break and just rather sell my gear and not have to work for a few years. And then I went one month, straight non-stop, for hiking. I just thought, ‘I want to do something completely different and check what’s up, what I want to do, and what’s going on in my life’ and all that stuff. And it really was a little bit of a turning point to me. And, yeah, I just kept doing it since then. It’s been somehow… I have a feeling like, you always, everytime you come back it doesn’t matter if it’s raining, it’s not comfortable, not even remotely comfortable. I have been close to dying several times there and there’s no phone range, there’s nobody there. If you break your foot, that’s enough to kill you, because you run out of food and you cannot… often times I am 40 to 50 kilometers away from a road, so you are in the wilderness and without any safety net. And the terrain is pretty hardcore and you have to know how to survive there. It’s not hospitable by any means. It’s not sunday walks. It’s more extreme in a way. But everytime I come back, I have a feeling you come back as a better person. It humbles you. I guess also that you have to just face your own fears and you have to be by yourself. Like, let’s say seven days. I think many people would just go nuts. Just by that. They are not able to be quiet for seven days. They are not able to face their own thoughts and fears and all that stuff for seven days, ten days, whatever. I thrive in that. I find it extremely exhilarating in a way. You process… it’s not a therapy, it’s more a meditative, a silent retreat. Like you just really rewind, do a little recap of what’s going on, and it’s a good place then to go forward. You reset and you move on. It’s life at its core, in a way. Hardcore, hardcore. I’m really into the whole hiking thing but I rather do it than talk about it. I don’t think it inspires my music anyhow. I think all this romanticism about Rakka… it’s not really like... I don’t want to downplay either, but it’s just press and you have to say something about something when you put records out. I’ve done a few records already, it’s hard to come up… if there’s a chance to use something, ‘OK, this is the record, this is what it’s about,’ it’s really relieving that you don’t have to think about it. Especially nowadays, like labels, like, ‘OK, what’s the angle and what’s all this shit and what’s the special story about the record.’ I’m really just happy to make music. But nowadays, as we know, it’s not really what matters so much anymore. But if you can tie in a nice story, people might pay attention for two minutes. That was maybe the hiking part that many people got drawn into but for me I think I escape all the bullshit with hiking, it’s not that I go there to get more inspiration. And I don’t make music about hiking, that’s for sure. Like maybe the music is a little bit... I mean they’re both private, but music has been my work at times and I do it all the time, even if it doesn’t any more pay the bills, it’s something I cannot really choose not to do. I’ve been doing it since I was five years old. I’ve always been fascinated about music and somehow had this urge to hit things and make sounds. But the hiking is just private escapism in a way, or just private. Well, it’s a holiday. You need to have a break. I spent a lot of time in the studio and it’s good to do something else for awhile.

KP: Yeah, I won’t delve into it too much further but just wanted to ask, ‘cause every year I try to spend about a week in the desert. So very different environment. A bit more developed. But similarly I kind of find the quiet and isolation, kind of endless horizon, seeing this landscape shaped by these processes that have been going on for much longer than you and are much bigger than you and it is a very humbling, regenerative experience.

SR: I’ve never been to a desert proper, but I went to Abu Dhabi some years ago and I hired a car where they took me where they filmed Star Wars. Just pure, like dunes, it was really hardcore. But, yeah, we drove a whole day to the border of Oman and just hundreds of kilometers of sand and it really also touched me. But that’s really hardcore, like there you die.

KP: Yeah, well this desert, there’s some dunes occasionally, but it’s mostly just bedrock.

SR: Oh, it’s not sand?

KP: Yeah, it’s mostly bedrock and then a lot of cacti that want to stab you.

SR: But you don’t have any water there?

KP: You would have to carry your water.

SR: That’s the hard part. ‘Cause where I go, you can drink everywhere. Clean water coming from sources and rivers and so you have just the cleanest water you can imagine everywhere. I would be uncomfortable going anywhere where it’s not possible to drink water all the time, because then you also have to carry so much and with the heat and all. In Texas?

KP: Yeah, so if you go a little west of where Austin’s at, you hit the Chihuahuan desert which extends up through Mexico kind of into... I would say through west Texas and then up to maybe the southern tip of Colorado and New Mexico and stuff. So that’s where the relatively flat center of North America starts going into the Rockies and starts getting mountainous. And kind of before, in the southwestern part of the states, before you start hitting the forested regions of the higher elevation Rockies, it’s all this bedrock desert with a lot of scrubbrush and cacti and not much cover. Hopefully you can find a tree to get some shade, but shade and water are definitely things you need to survive out there.

SR: Yeah, I’ve been to the states somewhat, but only cities. Now with the hiking, there’s this whole... there’s Pacific trails and all the trails in the states and the hiking culture’s quite big. I’ve been a little bit checking… I would really like to see the nature in the states. I haven’t really seen any nature in the USA, like it’s embarrassing almost. It’s only cities and taxis and hotels, what I’ve seen.

KP: Some of it’s great. Unfortunately, our national park system, there are some parks that aren’t well travelled but so much of it is kind of a drive-thru, overpopulated, nature destination type of thing and it can be hard to actually find some isolation in the national parks.

SR: Also the trails. I get the idea that it’s very busy there and it’s hard to find places where… cause for me, I’ve never been hiking where I saw another person. I’ve never seen a person where I go. It’s just pure wilderness. There are no trails. There are no people. Some animals. It’s a luxury. And I think because here we are quite isolated. There’s just not many people living here and there’s lots of space. But yeah, I appreciate this is quite a rare thing in the world. Maybe in Canada? Some parts could be. Alaska maybe?

KP: Yeah, Antarctica?

SR: Russia, some parts. But yeah it’s not easy. I totally know and I treat it as such. It’s a real luxury. It doesn’t feel like it but when you realize the scope of things it makes me also very humble and appreciative of them. And also that there is some clean nature still. Clean air. Clean water. It’s not an obvious thing anymore.

KP: Yeah. You kind of mentioned earlier that all of this is a kind of reprieve from a hyperaware, always turned-on, digital world that we live in. In a previous interview I read, you mentioned some issues with social media and stuff like that, so…

SR: I’m not always on. It’s a retreat from daily life, but I already closed my doors quite awhile back. I don’t have any social media or websites anymore. My wife does a little bit of Twitter since maybe half a year or year. She felt sorry for me. I have to have something. Sorry, I took over you, I just wanted to clarify that I’m not really always on at all. I’m not living that kind of life since… I’ve never been really, but especially nowadays it’s very lowkey and private and... But sorry, maybe you ask a question now that I’ve stopped you asking?

KP: No, that’s perfect. Yeah, I knew you kind of weren’t on social media… you mentioned album PR as well, that you have to kind of come up with this story or angle, whether or not it may be true...

SR: It’s not fake. It’s not that it’s not true but it’s not something I would necessarily want to bring up. It’s been a struggle for me for most of the time I’ve been making music, like I’ve never understood why music is not enough. You have to have a music video. You have to have a story about the album. Concerts are not enough, you have to have a video player, A/V shows. And it’s getting worse and worse. I don’t remember when it was that music was enough. And for me, music has always been enough. So that’s my dilemma a little bit. I don’t need the extras. But the world asks for more extras. ‘Cause music has, like you probably know, it has lost most of the value and meaning. And yeah I guess now we come to the sore point. It’s been painful to me for a very long time. I’m very passionate but also in a way naively romantic about music but it’s always been just my love and it’s been always enough for me. It’s been painful and it’s still very painful to see what has become… But yeah, clearly music is not much on its own.

KP: Yeah, so I know you’ve got the Bandcamp subscription…

SR: Sorry, did you cut off? I don’t know if you heard what I said.

KP: The video froze up but I was able to hear you.

SR: OK cool. I live in the middle of nowhere but I have ultrafast internet. I have gigabytes connection here. Lightpipe.

KP: Yeah, and I live in the middle of a city and we’ve got pretty poor internet…

SR: Yeah, it happens. Like I speak to most of the places in the world, doesn’t matter if it’s Berlin or New York, stuck all the time. Super slow internet. And I’m here in a small island with less than a thousand inhabitants and I have like gigabytes coming out. It’s pretty cool.

KP: So I know you’re on Bandcamp now. Has that been a platform that you enjoy as far as being able to release music to subscribers without necessarily telling stories about it? There’s a bit of a social aspect to it as well, have you engaged with fans in that way?

SR: It’s quite difficult. I guess it’s more about just desperate measures. I realize I’m making zero money from music anymore and I’m spending all my days making music. I’ve been living off of music since I was 15 years old, and now I’m soon 45. And in some sense a known artist, but there’s no way I could make a living anymore. And not even like a little bit of living. I never studied anything. I don’t have any profession. I have no interest to make anything else. So I thought maybe the subscription thing would be something. Partially it was just like, ‘OK, is there any way to make any income from music?’ I thought the subscription would work because also with the music industry nowadays it’s pretty hard to… there’s so much releases all the time, and labels are overpacked to the brim with releases. So I have now for example, records coming out late ‘22 and I have finished them a year ago. It’s not the best place to be creatively. You finish something and then you wait like three years for the record to come out. Also the Rakka II, I finished more than two years ago. It’s not optimal, nowhere near. Bandcamp, financials aside, purely creative outlet, it’s nice to put stuff out right away but there’s like maybe eighty people subscribing. So now I’m making music super intensively and, maximum amount of people in the whole fucking planet of eight billion people, there’s eighty persons that might hear it and I don’t know how many people hear it and maybe two of them might say like ‘yeah, thanks.’ You know, it’s not super killing. But these are the times we are living in. Also when I stopped, when I sold my gear and took a break, then I made at least as much music as I’ve ever been making and I didn’t release any of it. It comes down to I would make music even if nobody listened to it. And I made music, maybe four or five albums worth, without playing it to anybody, just because I wanted to… for me, it’s a chance to… how would I say… I’m not done. I want to learn. I want to put effort into… especially now when I’m not making money out of music, it’s becoming more and more crucial, like what do I really want to do musically and artistically? Do I like it? Do I stand behind it? Do I enjoy doing it even if it never leaves the room? So with Bandcamp now there’s eighty people more than a few years ago when I didn’t play to anybody. But, you probably can tell, that I’m a little bit also unsure of what’s going on and what to make out of it. It’s interesting and it’s extremely challenging and at times pretty annoying. But it’s also like you know… again - I guess I use the word humble a lot - but it’s quite humbling when you think about what’s going on in the world right now with the music. I think I was quite lucky when I was young and just made a few records, and these were the CD times, and you could really quite make a decent living out of music if you were lucky enough, which I was. So coming from that experience, I’m still trying to understand and figure out what’s going on. I would like to make some sort of living out of music without having to make any compromises, but currently it’s really far away from reality. So I’m trying to just see what’s possible and most of all how to stay inspired and not get dragged down by all this bullshit. Spotify and streamings and you know. As much as I would like to be optimistic, it’s becoming harder and harder. Also when I talk to labels, they say like, ‘more and more magazines are closing, everything is closing and there’s only like bigger acts able to survive.’ But outlets are dying and record shops are closing and it’s pretty heavy. Everything’s commoditized to Spotify streams and Youtubes and I’m still not able to use Youtube. I cannot just listen to music that way. But yeah, it’s interesting.

KP: I guess, kind of making or releasing music to that smaller dedicated audience, has that freed you in any way from constraints that you feel with your more commercial releases?

SR: I really don’t have any commercial releases.

KP: Yeah yeah, sorry, I guess the releases that are kind of dressed up by the labels.

SR: Yeah, but I mean if they sell like a few hundred copies, it’s like, we’ve been selling like few hundred vinyls or having eighty people stream your stuff on bandcamp, in the end it’s really no difference.

KP: Gotcha

SR: I mean, what I do on Bandcamp is I put out stuff on a little bit of a moments notice, also to myself, I don’t try to… it’s interesting… it’s very difficult for me to admit it, I guess, but oftentimes unfinished demos last longer, they stay interesting longer, but it’s just super hard to… maybe I’m a little bit of a control type of person, but everybody I know is the same. They want to have it good. They want to finish something they do. But it’s a really thin line between finishing it and knowing when to stop working on it. I think I’m pretty good with it. I had problems with that earlier but now I’m quite comfortable with just… I know when it’s right. And maybe that’s why I’m ready to take a little bit more, not necessarily risks, but just exercise more of the idea that what if I don’t even try to finish it. What if I really just do something and let it be. And when I come back to those things after some months or whatever, more often than not they surprise me. Like, whoa, this has something that I’m pretty sure if I had continued working on it, that something would not be there anymore. What talks to me, and what touches me. And it’s rough edges but maybe it carries more emotion or maybe more intuition or something. But that is something that I’m doing with Bandcamp alot. I have lots of like rough things. Also because I want to put out stuff there and sometimes I’m working on other stuff which I’m not planning to put out on Bandcamp and then I realize like, ‘OK it’s been like three, four weeks I didn’t put out anything to the subscribers’ and then, ‘what do I have here, hmmm, OK,’ something I’ve worked on before and I just give myself two hours to wrap it up and then I just put it out. And that’s quite interesting. I like that, as a medium. It’s not that I want to release any shit. I don’t treat Bandcamp subscribers as B-class listeners, they are A+. But I’m happy to share those... in-progress... also, I’ve been doing, sometimes I have few concepts - I guess one of them is eventually gonna be an album. But I’m really in a way having a hard time to figure out how far I want to push it and I’m no way in a hurry, so I’ve been just doing different runs on same material. And it’s changing quite a lot every time. But in my studio, they are the same project names, but I just rewrite them and they become something quite different. On the Bandcamp, I released some tracks three times and you wouldn’t really quite recognize them, but they are the same track. I explain to people that this is a work in progress. This is the next step of that track. And next step of that track. So it’s trying to make the best out of it, what’s possible now. I think the main thing is to try to stay - I mean you cannot force yourself to stay - but hopefully stay creative and inspired. It’s not always easy. But this Bandcamp thing allows me to do something like that, that I would never be able to do otherwise. Some kind of Soundcloud or whatever could be maybe similar but… it feels really weird to have this very small group of people, but I guess I have to accept and very much respect that these guys are really interested in what I do. And if it’s so that there’s eighty people interested in what I do in the world, then what can I do. It’s not mainstream music I do. It also takes something to commit even ten bucks a month, but it’s money, you know. But yeah, interesting times.

KP: Yeah… I… Yeah… I don’t doubt that there’s a lot more people in the world who listen to and love your music, just might not be aware of Bandcamp subscriptions or, yeah, don’t necessarily wanna set aside the funds…

SR: Yeah but also all my records are available elsewhere for free, so you have to really be quite nerdy and into the… yeah, I’m not saying there’s only eighty people interested in my music. I figured that out, but still…

KP: Yeah, it’s a small subset of superfans. So you’ve got Fun is Not a Straight Line coming up in a month or so, was that recorded awhile ago or is that a more recent project?

SR: What is recent? But maybe it’s like year and a half, two years.

KP: Oh, gotcha, so it’s still on that same delayed cycle. But the story around it is that you’re exploring hip hop influences as well?

SR: Yeah, well… I don’t know where to begin without talking too much about it just like blah blah. I’ve been doing lots of quite experimental stuff. Like Rakka sounds quite poppy compared to what I’ve been doing in the studio a lot. It’s pretty demanding, especially if you do it like whole day, all day, every day. It’s not that I worry about my mental health but it’s really not easy. I cannot listen anymore… like I don’t listen to any music at home or, if I listen, then I listen to some like jazz ballads or something to reset. But yeah it’s a demanding… I’ve been just really interested in trying to push music, experimental music, to see what I could do. And I guess for whatever reason it is, I feel a little bit more of a balanced person - somehow funnily enough I can push the music into much more harsh and harder terrain. Whereas in the past when I was young I was really a walking, you know, complete fucking basketcase. Not very easy-going person in life in general, like lots of problems. And somehow that turned music into Entain and all these like heroin dubs and like endless [makes droning sound] where nothing is happening. But now when I am a little bit more standing on my feet, balanced, I feel like I can really really push music quite a lot into uncomfortable terrain and feel very comfortable and it’s almost like calming, like really going over the point. It’s just really grounding me. It’s quite interesting, like I wouldn’t expect that in a way. But anyway that’s what I figured out. But because I’ve been doing quite a lot of these exploratory, experimental things, there’s always been this poppy side in me, like what I did with Luomo a long time ago. So, I felt like at some point I really need to do something to balance, just to not get stuck on that like murder terrain. It’s like food. No matter how much you like Japanese food, after awhile you get sick of it, you want to eat then like, I don’t know, mediterranean. That’s about it, basically. I just wanted to do something to completely reset. You know, when I do some experimental stuff for a long time you easily get, especially with no touring and no interaction, you can a little bit get stuck in your own head space. And you don’t see the forest from the trees anymore necessarily. So I have always done... then I do something completely different. If it’s not going hiking for three months then I do some pop music, or I produce somebody else's album, or anything almost opposite or as far away as possible just to get the fuck out of that mind space for awhile, do something totally different for enjoyment. But also when I come back to that previous thing, I hear it from a completely different perspective. And that has saved me in a way, like then I just hear a little bit, ‘what was I trying to do, I don’t hear it anymore,’ just throw it away. Try again. It just gives a different point of view. So this Ripatti thing was partially that but also I was missing suddenly to do club music. I got really burned out with this Luomo stuff and the four to the floor housey stuff. I really did not want to do ever again any of that stuff. At some point I just realized like, ‘who am I kidding here?’ It’s just really not going anywhere. It’s just really quite rigid. I really put an effort to try to reinvent my own self with the four to the floor housey thing and I just had to admit I cannot take it anymore anywhere where I find it interesting. So I stopped doing it but after several years - quite many years - I missed… I don’t go to clubs, I don’t listen to club music but there’s something still I like about the idea of club music. Not to dance necessarily but to have that idea of club music in a way. I’ve been always quite fascinated by that, just the idea of music in a big space with big sound and able to move from that music. So I just wanted to do that again from a different perspective, different ideas. I heard, maybe ten years ago, I heard a little bit about the footwork stuff but mainly I read about it. I often find it’s even more interesting to read what people write about certain music than to listen to it. So I got quite inspired by what I read about footwork or juke or I don’t exactly know what we are talking about but this fast tempo sampling music. It somehow spoke to me theoretically. As an idea, I found it interesting and I felt inspired to play with stuff. I had been in parallel going with my Vladislav Delay projects, the tempos had been going up really fast. So I was already there with my productions that are going really fast and in a way rhythmic, but I wanted to take it completely elsewhere. Like not trying to feel uncomfortable with my Vladislav Delay things - I don’t have any need to make any club or dance music there - but I felt I’m touching something here which is not really what I want to do with that project but let’s really make a project then about that fast rhythmic stuff. I released and I made someEPs on my own label, very small numbers, but there were a few records that I made, maybe ten years ago, as Ripatti, which is sameish stuff, like fast, and sampling, and all. I took a break. But now a few years ago I revisited those ideas again because I feel like I stuck with too much experimental music around me, or what I’m doing, and I wanted to just lighten up the mood a little bit. Somehow the sampling, when I did the first round of those Ripatti releases, maybe ten years ago, I sampled lots of R&B and whatever, like Destiny’s Child and all these nice-sounding female voices and I felt like I had exhausted that avenue. I didn’t want to do that anymore, really. It’s quite cliche, you know, you have a beat and a sexy female voice there, I don’t want to have anything to do with that anymore. But I totally wanted to do sampling. I didn’t want to make my own sounds but I wanted to… you know, I’m still surrounded by popular culture. I still listen to hip hop a lot. I’ve been listening to rap music always. When I want to switch my brain off, or I want to get some challenging… when I’m stuck with something and feel like in a slump I put just some B.I.G. on and, fuck, you know, you get the swagger. It has certain functions.

KP: Are you kind of more drawn to the production side of it? Or the vocal cadences that the lyricists are coming up with?

SR: The rap. The rap. Production I don’t almost care at all. It actually started to bother me when it started to be too smart for awhile. And even now some of the trap stuff, I’m a little bit bothered by this hi-hat programming and all that. I don’t need music, I need basic… just carry the rap, serve the rap. And then I’m good. It’s funny, like all the old classics that I listen to, it doesn’t matter if it’s Nas or B.I.G. or Wu-Tang - maybe Wu-Tang is not a good example - but most of the stuff, if you start listening to the background, it’s really boring music, right? At least to me. I could not imagine listening to that without raps. Not for one second. It’s just really boring music to me. But when you have somebody telling stories and rapping over it, I’m totally cool, I’m really happy. And I don’t need anything more. I need the raps, I don’t need the music. To try to impress me or whatever or tell me anything, just stay out of the way of the rapper. Going back to the project, I just felt like OK I want to sample something but… little commentary of popular culture and my influences so I just took whatever I felt like sampling and it ended up being quite a lot of hip hop, rap.

KP: Who’re some of your favorite rappers, if you’re alright sharing?

SR: The classic ones. The older guys. Of the current stuff, which is more interesting to try to find good stuff there, but I really like Griselda, like Westside Gunn, I really got impressed by him. Also Freddie Gibbs. Big respect, I really love that album. I really just enjoy… I like gangsta rap. I am unashamedly a gangsta rap fan, always been. I listened to that stuff on my headphones when I was a kid. I never studied, I never worked, I started going sideways when I was young. And that probably plays a big role. But I was listening to like Nas and Mobb Deep and all the gangsta rap guys. I think it left a big mark in me. I mean now I’m an adult person and I… I don’t know, I find it funny I still get kicks out of listening to these young guys talking about stuff… coke rap… I can’t hide it, I like it. I cannot explain… there’s some weird thing about it, why I like it and I just stopped caring about it. I was quite bored of rap for a long time with this mumble rap thing going on and just champagne and shit like, you know, it didn’t speak to me at all. I didn’t listen to rap for like five years or something. But then with Griselda and all the east coast guys from like Buffalo and weird places started hitting, I really got reawakened by that stuff. I think it’s a good moment in rap music. In parts, more in the underground. I’m waiting for more interesting female rappers to come out. Like I listened to Lil’ Kim and Foxy Brown all these from the very moment they started and Nicki Minaj before she released any records. But they all turned into this thing a little bit too commercial. But I’m a really big fan of female rappers and I think more interesting stuff, when they stop trying to all mimic themselves and trying to just, you know, do the most common denominator thing, I think there’s good stuff ahead. Promising times. For rap music for sure.

KP: I guess just to switch gears a little bit, since you’re about to release this hip hop influenced project and over the past few years you’ve done some collaborations with Sly & Robbie, coming from the dub world, and then I saw in your subscription that you’ve been revisiting the quintet as well, with Lucio Capece and all that. And I’m vaguely aware you’re coming from a history of jazz drumming. But I guess I kind of wanted to ask - you mentioned it with the hip hop bit - but with the dub and jazz things, what draws you towards focusing on certain forms of music with a given project?

SR: Can you rephrase the question?

KP: Yeah, I guess with the Sly & Robbie project and quintet projects, what do you feel you’re able to do with those that you’re not necessarily able to do with your own stuff?

SR: Well the most obvious is the fact that my solo stuff I do alone, and then the other stuff is not alone. For quite a long time I’ve been doing, in parallel with my own solo stuff, I’ve been doing collaborations like when I was in Berlin I did many years with Moritz von Oswald Trio. And then I had the [Vladislav Delay] Quartet in Berlin also. You know, when you do your own stuff, you’re stroking your ego in unhealthy ways often, you know, you can decide everything and it’s hedonistic stuff in a way. I come from band background and jazz background, improvising the feeling of each other. I try to take my experience from that interaction and try to create fantasy things in the studio, like I just try to reinvent some of those things that would happen by nature in bands and things, I try to do those like accidental interactions and things, I try to do a lot of that in studio. It can make it more interesting, but it can never achieve the same. I do enjoy interaction with people, especially after I’ve done my own stuff, it’s really nice to go and do collaborations and even do stuff where you are working for somebody else, really just doing a service job in a way, as long as it’s interesting. So you are really not there to boost your own ego and stroke your ego but you are really there to either trying to fulfill somebody else’s wish and bringing your part in it or just enjoying interaction and… But there are many reasons, like Sly & Robbie, I am a huge fan. It’s a great honor to be able to play with these guys and I really got quite close with them. I’ve always been very inspired by Jamaican culture, not only musically. So it was amazing to go there again and spend a few weeks there and just record, hang out, do stuff. And you know, legends or not, when they’re doing their instrument things they fucking kill it. As a drummer also, ex-drummer, it’s also incredible to witness Sly, not a young boy any more, and how he’s still doing it. It’s inspiring. Also like, I’m not getting any younger. It’s really nice to do whatever possible to get inspired, challenged, get a little bit out of your comfort zone. That’s maybe the most interesting thing, that you do stuff where you’re not comfortable, and you do stuff which is not expected. I could put the harsh word - hate - I really hate repeating myself. I really see zero reason in doing things you have done before. I see that doing no service to anybody. It’s really just as simple as that. I’m trying to follow my harsh words and not fucking repeat myself. I admire some people who have built, they have done, they have repeated themselves ad nauseum, and they have built a career and they have built a following and people for sure know that when that brand releases the next record they know what they expect. And that gives them probably eventually a big following because, you know, if you repeat something enough times it starts to stick. But I’m not able to. I start to feel like I’m selling my ass after even thinking about that stuff. It’d be a whole different animal and I’m difficult in that sense. Life is too short to repeat things. Even you go fully wrong, even you really fucking fail big time it doesn’t matter, at least you tried. You don’t fail, you didn’t try. It’s really simple stuff. And especially now when we are not making a living. There is no money involved almost. It’s like, ‘OK what am I here for, what do I want to do?’ And I don’t want to play safe. I wanna explore. I wanna be challenged. I wanna fail. I wanna try new things. I’m quite curious. I get bored, also, very easily. By nature I need to do different things. I get really bored easily. I cannot - it’s not even if I want or not - I cannot repeat myself trying to do something again. It’s totally pointless and I would just get like self-loathing. It’s not even funny, it’s sometimes quite painful. Sometimes like last year I’ve been doing so much music I hear very potentially quite nice things that I recognize that, ‘OK, people who liked Multila or maybe this or that album from my past, they would certainly love this stuff.’ But, you know, it’s trashed already. I didn’t even keep it. I’m not here also to entertain people. If you like my stuff, you have to accept that it’s gonna change. It has to change. Also anybody I admire musically - now we are not talking about hip hop but like my love in jazz for example, people I really admire like Miles or Coltrane, I mean fuck they reinvented themselves like four, five times in their career. Miles Davis, he stopped playing ballads. He could have just a comfortable nice life and play the world fucking over and just do the same fucking ballads over and over and he stopped playing ballads because it’s too easy. Or Dylan, turning from acoustic to electric. Sadly, there are not many examples even. But that even more highlights the idea I’m talking about here, that that’s the thing we should be doing. Too many people just really get stuck in their idiom and try to I guess pay the bills or I don’t know. I don’t want to challenge anybody or question anybody’s motives there but anyway I was always really touched by… also how Coltrane, for example, what he did, just really throwing everything he had worked towards, you know, A Love Supreme, fucking one of the greatest records ever, and he stopped doing that pretty soon and just really went a totally different style. That takes guts, it really speaks to me a lot. And maybe because since I was a kid - I started doing jazz when I was 13 or something - I really fell in love with that stuff. So it’s really engrained in me when I was really young when I started exploring those things - maybe I was 15 when I first heard… like Miles’ electric stuff, I thought like, ‘what the fuck is this,’ like you know after Kind of Blue, you hit Live-Evil or something like Bitches Brew. Same guy? Same what? Like nothing. There’s almost no common ground until you go deep and start analyzing it. After awhile it really just made the biggest impression in me and I thought that’s what we should try to do. We really should investigate, try to research, and push us towards one goal and when you reach that, or not, even if you fail, just move on. I guess you can hear it, I’m quite passionate about that part. But, yeah, it’s one of the crucial points in why am I doing anything anyway. But that’s why I’m doing the quintets and collaborations and things. Just to keep it interesting and try to look for different things and maybe serve some motives which are not even music-related like even a chance to hang out with guys I admire and want to learn from them.

KP: Yeah, I think it’s super common in the jazz world to always have a rotating community of musicians and every time you add someone new to the mix it always challenges everyone’s perspectives with whatever they add. Definitely can be a good environment to grow.

SR: I’m so so huge fan of what different quintets Miles for example had, like how he made those people work, how he found those guys, and how he made them to do their utmost best but still become even more than the sum of their parts together. Really it’s quite brilliant. I mean he took these young kids like Hancock and Tony Williams, Ron Carter, Wayne Shorter, they were really kids, like underage some of them, when they started playing.

KP: Yeah. You mentioned that your sound is always changing - and that’s honestly kind of what listeners of your music expect - or developing, but are there some general overarching ideas that you find yourself returning to throughout the years?

SR: Not really.

KP: Yeah, just always challenging what you’ve already got?

SR: I guess you respond to life, in a way. And life changes all the time. So I mean of course there’s certain... when it comes to my own solo music, oftentimes I still try to reach that same idea I had when I was 18 and doing my first electronic things. I don’t know what it is, it’s this inner feeling. Even though the music sounds very different, I still somehow connect to some thread that goes through but it’s super conceptual or whatever. Like I said I cannot put any words, I cannot describe what it is, it’s just some unconscious thing. But, yeah, not really, no, not really, can’t say.

KP: OK, and then I guess totally switching gears, I understand that you’re surrounded by writers. That you have a lot of writers in your family. And also it seems like the track titles for Visa and Rakka have fun with rhyming. I wanted to ask if you write at all or get anything out of writing or if that informs your stuff at all.

SR: Well, I read a lot. And I’m inspired by books probably more than music. You know it’s this thing like when your parents and grandparents and everybody’s writing, the first thing you decide when you’re young is like, ‘I will fucking never write.’ I think about five years ago I started like, ‘hmmm, it would be pretty nice to write.’ And I’ve been toying with that. Yeah, a few times I was close to just flying off somewhere for half a year to write. I didn’t pull the trigger yet but I would say it’s just a question of time when I write. Funny enough when I’m hiking, that’s when I really... I have almost ready-made stories already in my mind. And I started taking notes already. So yeah I’m a little going towards it, but very slowly and I’m really not gonna rush it. And I learned, because I started making music without any technical education, without knowledge in producing music. I had zero knowledge. I completely stumbled by accident with electronic gear and tried to figure out how to make it work for me. I totally jumped from jazz drums into having these weird blinking lights and not really knowing what they do. In a way, you can only live that through once. Since then I’ve been trying to unlearn almost everything I know and try to get to that beginner state because that’s where you make your best things I guess, or more original things. So I know that, when I write, I can only write once, as a virgin. And I wanna really... not put pressure on it but also not throw away that chance. I really wanna enjoy it. And coming from that music experience, I know a little bit, not what to expect, but what to cherish maybe. So I’m super easy going with the writing thing but yeah, I’m slowly working on it in the subconscious. Sometime stories stay a week, sometimes a few months. But I didn’t yet get something strong that that would really stick, and make me stop making music and really just fly somewhere and write a book, or outline a book or something. I guess I’m - maybe you could call it I’m playing safe - I don’t wanna take risks, I wanna wait until I get a good enough idea, maybe it’s that. But maybe it’s also that I’m really also quite busy with music and I don’t actually want to stop making music. So maybe I’m waiting that I have such an urge to write a book that I have to stop making music, and then it’s time to write the book. But yeah, you know, I’m still young.

KP: Yeah yeah. Do you have some things that you pay attention to in writing? Like - just cause you make music based on pulse - do you pay particular attention to like cadence in writing? Or any kind of stylistic decisions that you’re drawn towards?

SR: Well, short answer, no. I pay attention. But I try not to get into that rabbit hole. I can appreciate high literature, if that’s the right word for it, but I can also appreciate punk literature equally. I don’t even know which one I like better. But, yeah, I noticed my reading habits shifted a little bit and I actually had to put a stop to it, I don’t want to read as an analytic… I wanna enjoy reading. I don’t wanna analyze too much how they write and what’s their phrasing and what’s their this and that and yeah. I don’t speak any language well anymore. I think in English; I dream in English. But I lack vocabulary. But my Finnish is not much better. I think I would probably write in English, ask somebody to translate in Finnish, read it again, and then translate it back to English. Not by myself but I would probably write my first draft in English.

KP: What are some writers that you’re drawn towards?

SR: The Wallace book, Foster Wallace, Infinite Jest.

KP: That’s a hefty one.

SR: That’s maybe my favorite book ever, one of the top three…

KP: Are you a fan of William Gaddis and Thomas Pynchon and stuff too?

SR: I mean, yeah. Pynchon, yeah. I quite like Inherent Vice even, as a pop writing. I really liked Murakami 1Q84. Hmmm, wonder what the other books are that I have been inspired by lately.... I read the Foster Wallace book again not too long ago and somehow after that felt like I don’t wanna read anything. It was super hard to read anything, it’s just really like nothing spoke to me. It’s just that’s the Miles Davis to me. It really hit me hard the second time I read it.

KP: My wife has a copy in the house but I’ve never read it. So this might be the time to get started.

SR: I’m massive fan of that book. And It’s one of the only books where I really don’t mind that it’s not even - he doesn’t even try to stop the book. It’s like fucking long and it just stops when it stops and there’s no ending to it. Most of the time I’m bothered about that in books. Nobody can get good endings to books. And he doesn’t even try. But it’s a little bit of a bad habit because I’m so nerdy with music stuff, with the data and names and stuff, but when I read, half the time I cannot say what the writer’s name is. I don’t want to be name dropping, I’m really not able to do that, I don’t want to do that, I don’t want to be able to do that. Of course, it’s good to know and acknowledge who the writer is and what they are but somehow I don’t seem to be keeping the names. Nowadays oftentimes I read on the Kindle, ‘cause when I go hike I have just the Kindle, I don’t even see the cover anymore. In a way, then what’s the real value? The real value is the story and writing so I’m just focusing on that and I don’t even know sometimes who these people are. In good and bad ways, interesting. But surely if i like something i end up finding out more about the person and what else is out there from that person.

KP: Well, that’s all that I kind of had planned. Did you have anything that you wanted to shout out or talk about?

SR: Well, I want to shout out all the young rappers out there to keep it real! [laughs] no no no, I’m here to serve you, so just whatever you have in mind…

annotations

annotations is a recurring feature sampling graphic or other non-traditional notation with context and a preference for recent work with recorded examples, in the spirit of John Cage & Alison Knowles’ Notations and Theresa Sauer’s Notations 21. As a non-musician illiterate in traditional notation, I believe alternative notation can offer intuitive pathways to enriching interpretations of the sound it symbolizes and, even better, sound in general. For many listeners, music is more often approached through performances and recordings, rather than through compositional practices; these scores might offer additional information, hence the name, annotations.

Other resources exploring alternative notation include: Carl Bergstroem-Nielsen’s IM-OS journal; Christopher Williams’ Tactile Paths; and various writings of Daniel Barbiero, including Graphic Scores & Musical Post-Literacy and the liner notes for In/Completion.

All scores copied in this newsletter are done so with permission of the composer for the purpose of this newsletter only, and are not to be further copied without their permission. If you are a composer utilizing non-traditional notation and are interested in featuring your work in this newsletter, please reach out to harmonicseries21@gmail.com for permissions and purchasing of your scores; if you know a composer that might be interested, please share this call.

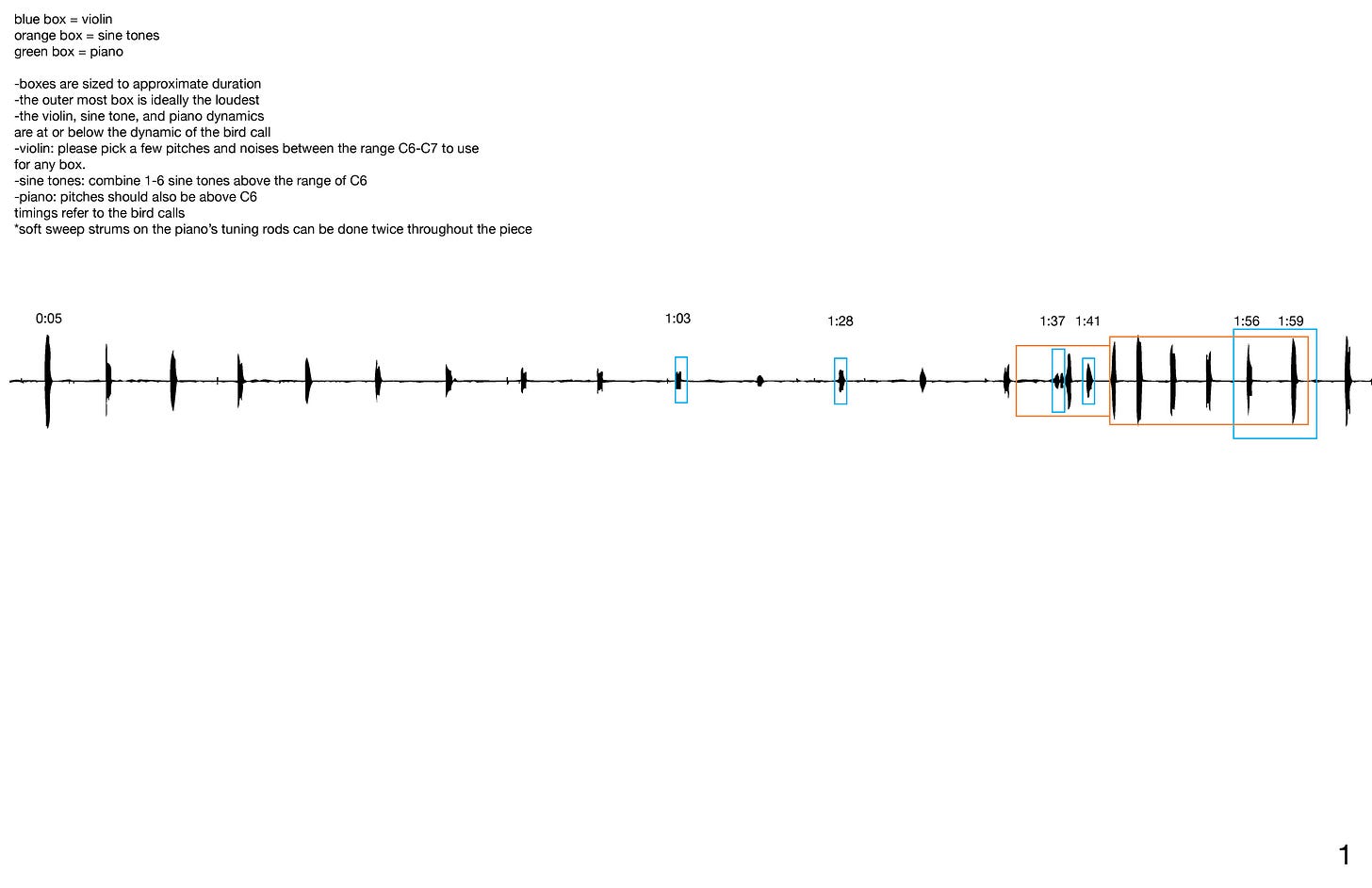

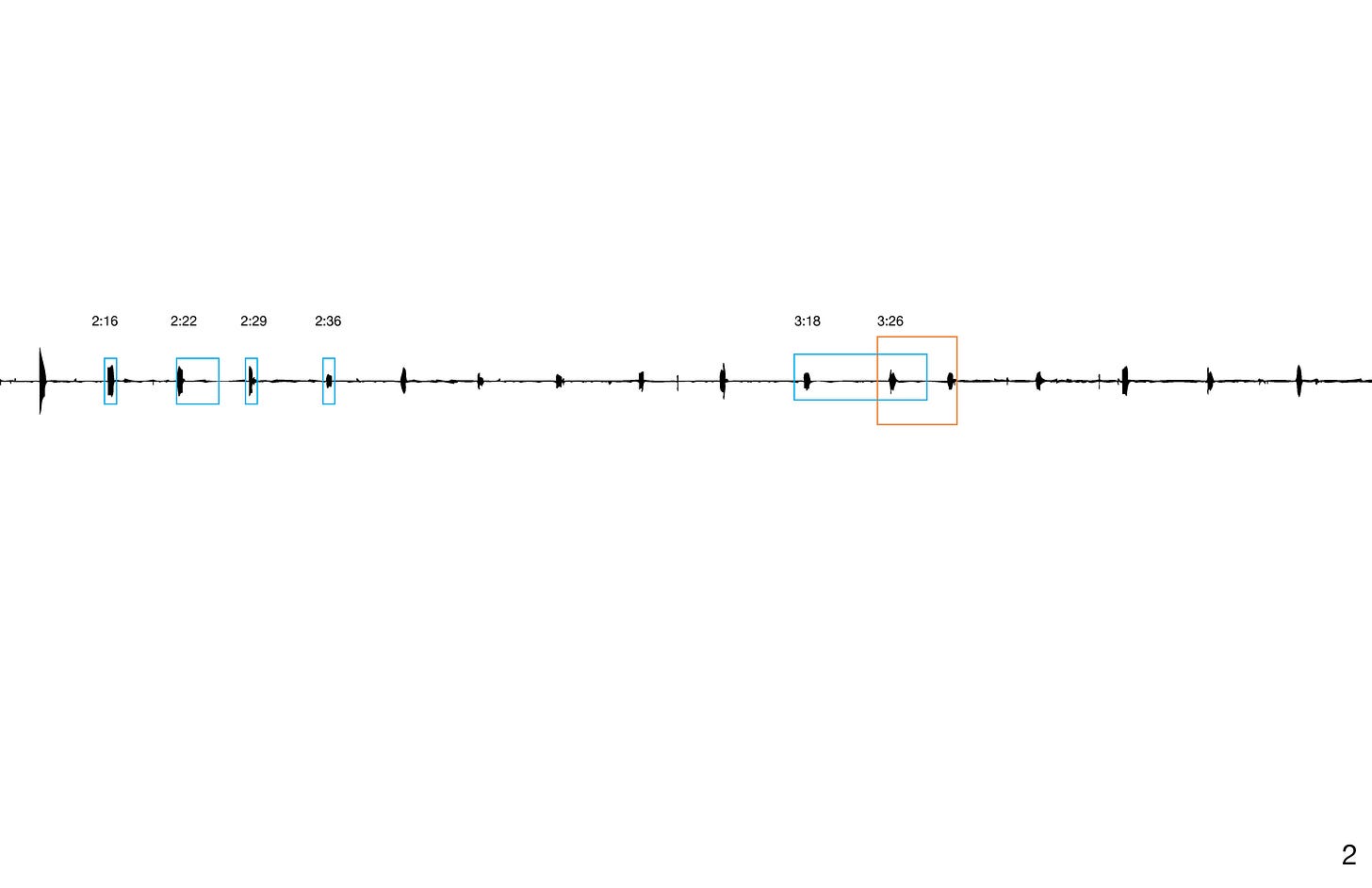

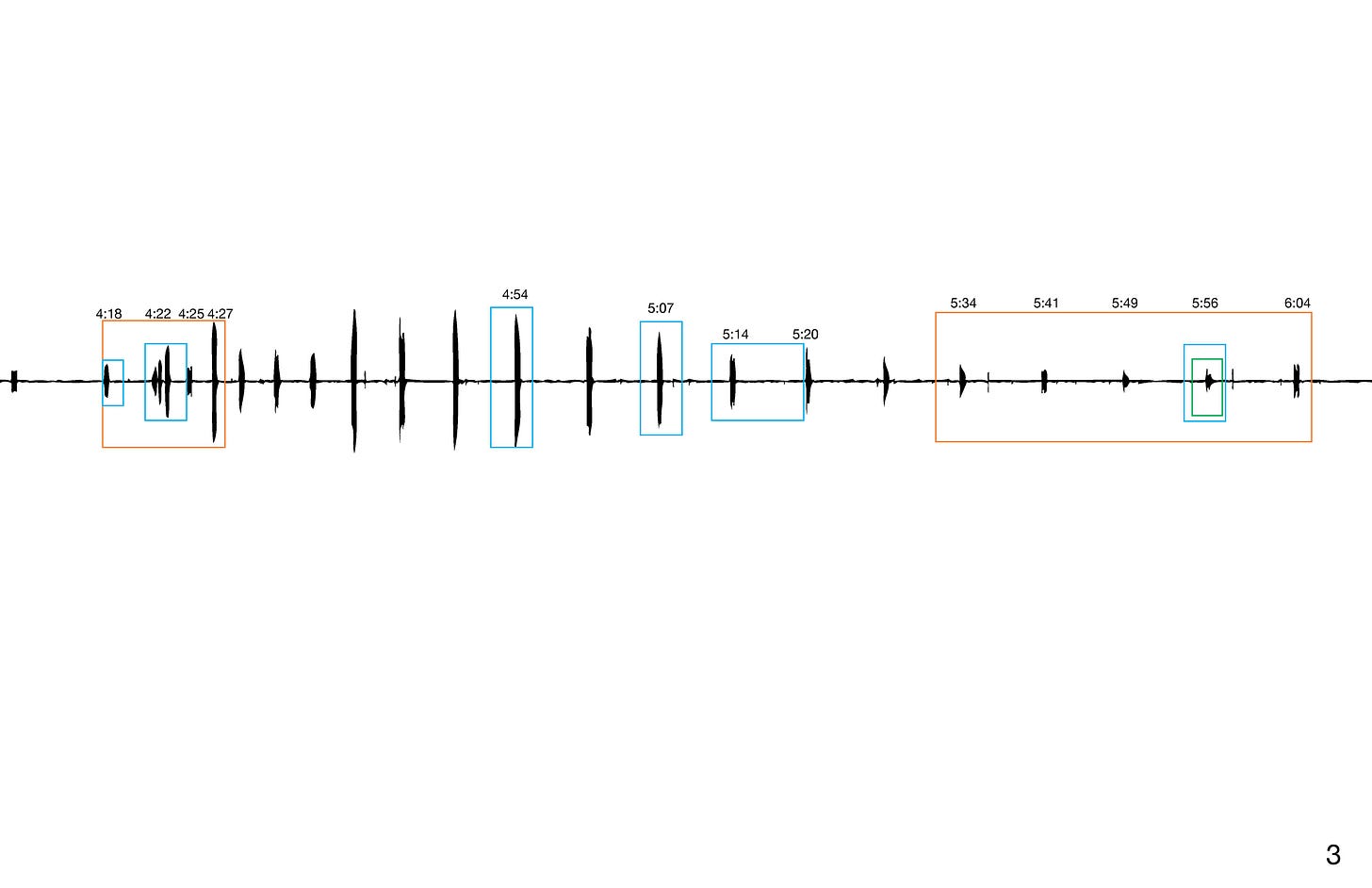

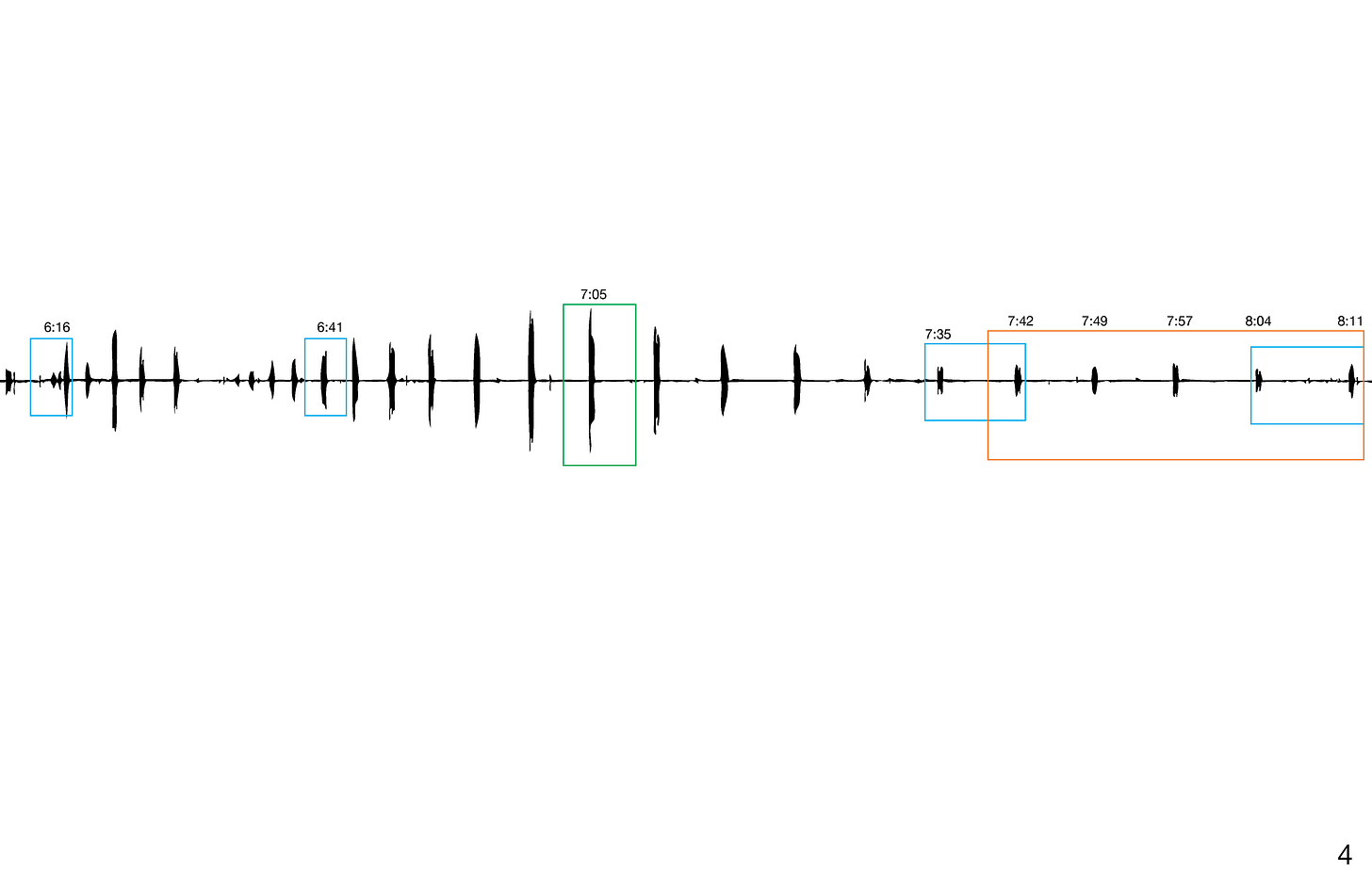

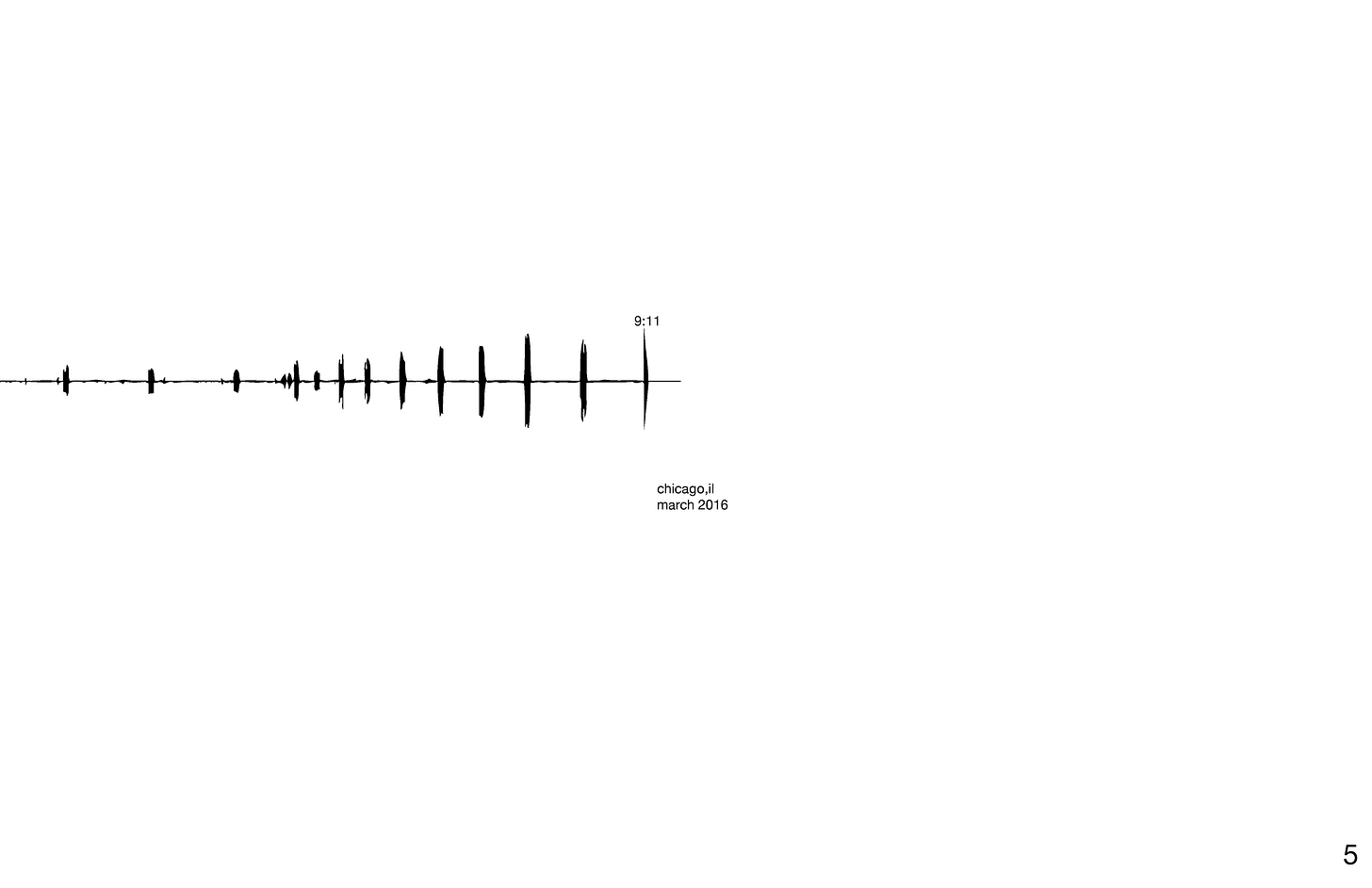

Ryan Packard - microcerculus marginatus (2016)

Ryan Packard is a percussionist, composer, and sound artist that works in a broad variety of contexts and cultivates intimate environments through their compositions. microcerculus marginatus is a 2016 composition for violin, piano, sine tones, and field recording. Its title is the taxonomic name for the scaly-breasted wren or southern nightingale-wren of Central and South America, the song of which features prominently in the work; perhaps tangentially interesting, I gathered that its song varies across its range, suggesting more than one species under the taxonomy. The score presents a spectrogram of a field recording of the birdsong with boxes - the color of which indicates instrument, the length duration, the height dynamics - and approximate time markers for some birdcalls. Possible pitches and an invitation for two “soft sweep strums” are indicated in the directions. The recording included is performed by Myra Hinrichs on violin and Packard on piano and sine tones.

The intuitive symbology and simplicity of the score reveals the close listening required of the performers. Not just in their relative dynamics but also the placement of their soundings, some boxes aligning with the very end or beginning of a call or, around 1:37, dissecting a call. While time markers on some calls certainly help, I imagine the regularity of the song helps moreso, its beat beautifully visualized in the spectrogram, its dynamics across time forming a wavelike pattern. Maybe the instrumentation reflects some regularity and waves too, the number of calls the violin sounds besides almost consistently patterned a repeating 1-1-1-1-2 or the duration of and between sines a wave cycle though all with organic variation. Except for the two piano key soundings, the timbres nearly reflect those of the field recording too. The screech of the violin its own call and song. Sine tones like bugs chirruping among the rooster and other birds low in the recording. The two unmarked “soft sweep strums” rain on leaves or some other motion blending well with the more anonymous movement of the field recording or performance. The piano key soundings interestingly sound the most human and the least patterned. It strikes me as an ecological recording, not just because of the field recording but because it requires the performers to maintain awareness and consciousness around their relative place and adapt to others in its variations.

For additional listening, here’s a 2021 presentation of four works, including a solo cello movement composed in 2021.

reviews

While reviews here can be about anything they are most often about recordings of sound. For some interesting perspectives on this topic, Frantz Loriot’s Recordedness is an interview-based project exploring the nature of recordings.

Bent Duo - Ramble (self-released, 2021)

David Friend and Bill Solomon craft sensual environments for field recordings and electronics on the two half-hour tracks of Ramble.

In 2019, Bent Duo constructed a performance installation in a garden that invited people to explore the sounds of cruising in a safe environment and subsequently arranged some recordings of it with electronic accompaniment to compose Ramble. Through excerpts of literature from Raul Espinoza’s Cruising: An Intimate History of a Radical Pasttime and several other sources, the accompanying zine contextualizes cruising as a dismantling of the hierarchical power structures often associated with private heterosexual interaction at least in part through public negotiation of explicit consent in which each assumes mutual risk for mutual pleasure. Top? Bottom? Kink? Suck? Reflected in the equal time given to “Top” and “Bottom” and perhaps in the rousing climax, in which two moaning voices are heard together whereas before there might be only one. Some of the sounds include a lofi squelch, its crackles and pops signaling the DIY necessities of a culture forced underground and its fleshiness and suck the sensuality to come. Ambient washes like breath. Singing sines that chirp and chirrup like birds and evening bugs. An electric churn like the rhythmic slap of skin against skin. Reverbed Mori-esque organic electric percussion. A brief keyboard melody. Moans of pleasure and heavy breathing. With time some sounds become more naked. The temporally stretched breath and moans of the ambient washes reveal themselves. The birdsong becomes clear. Maybe that churn is the slap of skin on skin. But as if to indicate the fever dream of climax, time appears increasingly cut and collaged, the birdsong and moans manipulated in frenzied ways, one moan extended with seemingly increasing speed and decreasing volume like a rocket, others chopped together rhythmically.

Sam Dunscombe - Outside Ludlow / Desert Disco (Black Truffle, 2021)

Sam Dunscombe arranges found sounds and field recordings with organ and synthesizer accompaniment on the two sidelong environments, “Outside Ludlow” and “Desert Disco.”

“Outside Ludlow” is a strata of distinctive layers. The martial beat of some corporeal kick drum carpet bombing that the notes reveal is actually explosions from marine corps or mining operations near the titular ghost town around which Dunscombe recorded. The tension of a sustained scratched whine. The sucking doppler whirr of a train and its fading horns like soul string swells. The shivering and tremorous percussion of something like skipping. The maelstrom noise of ground nested bees or feeding flies swarming. The errant romanticism and conquest of a kind of gothic organ nestled in this soundscape. Its layers dynamically weave to reveal a tapestry seemingly depicting associations of manifest destiny and its post-apocalypse in the desert. The violent progress of military and mining and trains and western religion across the desert matching and exceeding that hostile environment’s desiccating heat, disintegrating wind, bold exhibition of death in its preservation of bones to mold a scape of desolation reflected in this bleak sound. “Desert Disco” is similarly layered but feels more static, the various cycles in the pulsing polyrhythm phasing in and out of beat. Though they diverge dynamically towards ecstatic ends. Whatever human sound these tapes held are muted and buried, their monotony decaying to more closely resemble the more diverse dynamic relationships between the environmental sounds of the first track.

Julia Eckhardt - Time Suspension (Back and Forth) (Takuroku, 2021)

Julia Eckhardt overlays a month of daily, minute-long solo viola improvisations and their reproductions from memory on the 30’ pandemic piece, Time Suspension (Back and Forth).

Each day for a month, Eckhardt reproduced the improvisation of the previous day from memory and then improvised something new for a minute. Yesterday and today are then overlaid, the improvisation and its memory concurrently played. Each minute is marked with a pause. Today’s improvisation is informed in varying degrees by the memory of yesterday’s, sometimes quite similar as if in continuation, sometimes not. The more obvious the vector of lineage from day to day in performance, the more time appears to flow in reverse when listening - I often thought I was listening to the memory before the original until (I think) I figured out the overlay pattern. The displacement of memory and present into each other, with a possible perception that the memory extends before its origin, and the momentum-stopping silence punctuating each minute lends an undertow to time. Its sounds are interesting too. The cadence of the return of the bow. The pulses of harmonic beatings. The percussion of pizzicato, tapping, rain, walking away. The coarseness of close-mic’d breath. The repeating rhythms of birdsong. In the context of this kind of Penrose or Möbius time, some of these discrete beats interrupting the otherwise sustained sounding of the viola might begin to assume the characters of crackles and clicks in tape loops or something else metronomic, the minute-long cells of sometimes similar material maybe already recalling such a structure. A subdivided and reconstructed time.

The component tracks can be heard here and the accompanying film snapshotting the atmospheres of the days during recording can be experienced below.

https://www.cafeoto.co.uk/shop/julia-eckhardt-time-suspension-back-and-forth/

Barbara Monk Feldman - Verses (Another Timbre, 2021)

Percussionist George Barton, violinist Mira Benjamin, and pianist Siwan Rhys perform five Barbara Monk Feldman compositions - three solos, a duo, and a trio - for 72’ of spacious, melodic chamber music on Verses.

For all its sparsity there is little silence. The long reverberating decay of bell and piano and vibraphone a field of gradient brightness and saturation, undulating into the unsounding, fading but rarely fully, another sounding beginning as the previous melody draws near inaudibility. The many-hued melodies capacitated by the broad tonalities of their many bars and keys and the melodies themselves of seemingly different saturations, viscous in time, slow and slower and sometimes so slow they are unmelodies. Dissolved structure. Pure color. As abstract visuals do, each sound invites a detailed listen to its individual complexities through time and its mutable relationships to others in space. The solo “Verses for Vibraphone” and “Clear Edge” for solo piano, composed in nearby years, allow some silence, appear more angular, juxtapose high and low registers, contrasting bold colors with bars of others and negative space. The trio “The Northern Shore” seems more visual realism, summoning images of tumbling waves in the discrete crash of piano and vibraphone, extended by sustained violin like wash skating shallow and flat across the beach, short percussive trills miniature kerfuffles of water over the topographies of shells and footprints and castles. I’m surely biased by the context, but the way in which the pieces arrange silence, sound, and space, tone, melody, and color evokes painterly decisions as much as musical ones.

Rip Hayman - Waves: Real and Imagined (Recital, 2021)

Composer Rip Hayman presents two sidelong seafaring works for multi-tracked flute and field recording on Waves: Real and Imagined.

“Waves for Flutes” is a 1977 recording of multi-tracked flutes performed by Hayman. Its free-spirited lines sometimes sustained, but more often melodic flights. Sustained segments radiate their pulsing harmonics, forming beating patterns, siren songs, waves imagined. But the interwoven melodies do too, their crosswise movements evoking melancholy and ecstasy simultaneously, emotively beating the mind as if suspended in waves, dragged by the undertow, bobbed up and down, hit by the wind waves and the rogues too. “Seascapes” is composed of field recordings of wind and water around a ship. The sounds of slow wind and water lapping at the hull. Howling wind blowing through the baffling sails and masts, its force folding the sea like wet clay to crack against and quake the ship, whistling while it works. And then perhaps dripping and draining and bailed as if it breached the ship. The piece plays at the inherited physiological reactions to sound, the ominous volume and such a celerity that belies its crushing mass as intuitively terrifying as a panther’s growl or a snake’s rattle. Likewise the calm of relative inertia.

José Luis Hurtado - Parametrical Counterpoint (KAIROS, 2021)

Parametrical Counterpoint is a 50’ portrait release of composer José Luis Hurtado featuring six recordings of three compositions performed by Talea Ensemble bookended by two solo piano pieces performed by the composer and showcasing a density of contrapuntal energy and activity.

The title composition is two independently conducted octets separately performing their own versions of the modular, open score with a choice to play at 60 or 120bps. Its four versions demonstrate its interpretive malleability, each sounding identifiably similar and simultaneously distinct, likewise each version sounding as if its falling apart and reassembling at once, a bead of mercury in a tray shattering and globbing together in unending movement. “Retour” is particularly percussive, its string pizzicato, wind pops and trills, and muted piano hammerings a complex polyrhythm of beats and their subdivisions, though its shifting dynamics, register, and density are more dimensional web than the layer cake that polyrhythms can be. Similarly, the cyclical echo of waves of string trills of various timbres in “Incandescent” like planes of contrasting spatiality condensed to one dimension, but more disjointed than cubism, a particularly colorful suprematism, with the vitality of action painting. The opening piano solo, “The caged, the immured,” juxtaposes the sharp high register and booming low register, melodic movement and insistent hammering, low and high density and volume together. And the closing piano solo, “Le Stelle,” with electronic accompaniment, contrasting a distanced muffled percussion and glitchy rings with bright piano twinklings like stars or fireflies in the black on black colorfield of night. Underpinning it all is the superimposition of the dualistic, high and low density and dynamics in the same space, high and low tempos and registers in the same space, cosmopolitan composition with a catalytic energy for a dizzying density.

The Talea Ensemble on this recording is: Stuart Breczinski (oboe); Barry Crawford (flute); Brian Ellingsen (contrabass); Stephen Gosling (piano); Chris Gross (cello); Marianne Gythfeldt (bass clarinet); Sunghae Anna Lim (violin); Alex Lipowski (percussion); Jeffrey Missal (trumpet); Adrian Morejon (bassoon); David Nelson (trombone); John Popham (Cello); and Ben Russell (violin).

https://www.joseluishurtado.net/parametricalcounterpointcd

Seth Kasselman - UV Catamaran (self-released, 2021)

Seth Kasselman produces aqueous electric environments across four tracks on the 40’ UV Catamaran.

I couldn’t shake a brief comparison to Monolake, Jan Jelinek, and Oval. Not so much for the glitched aesthetics - which are certainly here in some drops, pops, clicks, cuts, bleeps, and bloops - or a beatcentricity - which, while more of an atmospheric affair, characterizes certain segments here - but rather the bubbly energy, relaxed rippling reverb, and sunny human-in-the-machine intonation that characterizes some of their work. There’s something aquatic there that’s distilled here, though less severe than the Germans’ stuff, lighter, more buoyant. A lot of the musical material of UV Catamaran recalls water, if not in timbre then behavior. The ambient wash and swash. Sonar pings. Squelches. Bubbling and glugging. A delayed and muted smoothing as if heard in something thicker than air. The harried breathing of drowning. But its progressive forms sometimes stay in the air awhile, clipping birdsong, reed noodling, or an electric chittering or chirping recreating the ecology above the surface. In contrasting the two states and frequently featuring their tangling in bubbling and glugging and drowning sounds there’s something here that recognizes the tension between air and water, their unmixability. Though the nature of sound allows it to happily travel through both, if differently.

Frantz Loriot - While Whirling (Thin Wrist, 2021)

While Whirling is an eight-track, LP-length solo exhibition of textural technique for acoustic viola from Frantz Loriot.

A catalog of extraordinary timbres. Emotive overtone melodies unveiled from noise. Harmonic beatings out of sonorous bowings. Bucolic, bittersweet fiddling. The soft circular rasp of rubbing bow on wood. Lumbering heavy metal grooves. Dancing satyr fluting. Tuned tapping and singing bowl like hyperpiano. Turntablism. Rubbing balloons. Digital distortion. Chirping birdsong. Pick up sticks. Roulette. Beyond the spectacle of extended textures, these same techniques expand the rhythm and cadence of the instrument past bowing returns and plucking. From harmonic pulses to intentional beats tapped and scratched and more stochastic clusters of discrete soundings.

Anastassis Philippakopoulos - wind and light (elsewhere, 2021)

Jürg Frey and Anastassis Philippakopoulos perform seven sparse, melodic, solo Philippakopoulos compositions for clarinet in A and piano on the 40’ wind and light.

The clarinet pieces are measured, repatterning melodic cells of tones and breath separated by measured, generous silences. The piano pieces are similarly so but the rich reverberations of the instrument illuminate unsounded spaces. Their sequence alternates. It’s difficult to escape thinking about the material of silence when listening to the wandelweiser collective. The alternating pieces can frame unheard and heard sound or silence and sound as dialectic. Like the protean gradients of temperature and pressure ensure there is wind even when it is still. And like photic actions of reflection and refraction ensure there is always light even when it is dark. These pieces might ask you to sense sound where there is silence. Especially during the clarinet pieces, the listener might engage deeply to feel out the limits of their senses, hear how much of sound lingers in silence compared to the piano. I think that meditative state transposes to the rest of the music and lends a special gravity to the sounded melodies.

Additional interpretations of the piano pieces can be listened to on Melaine Dalibert’s Anastassis Philippakopoulos: piano works and on Dante Boon’s hannesson.boon.philippakopoulos.

Keith Rowe - Absence (Erstwhile Records, 2021)

Keith Rowe freely plays a melange of noise for contact microphones, radios, guitar, objects, and pedals on the half-hour set, Absence.

There’s a special kind of abrasion in the juxtaposition of beat-oriented popular music and the floury digestion of its more readily conveyed emotivity and the ambiguous forms of flayed textures from scraped contact mic and harried guitar and the more highbrow acrobatics it might invite in interpretation, sutured together by a click and hum and buzz blurring sources of undulating amplifier and the wavering fidelity of radio. Sometimes the other things appeal to the radio, a swipe of the contact mic signaling the entry and exit of a radio snippet or the guitar mimicking a melodic flourish of a song, metadecisions unexpected because they might be expected of other performers in this context. The notes reveal that the seismographic scratch that occurs two or three times in the middle third of the set to be Parkinson’s tremors, but you probably wouldn’t know it without context, the unintended seeming intended. For all the subversions of radio, like the the conflation of mass experience and personal experience or mixing chance processes into those of choice, the most jarring here occurs in the final two minutes, in which a classical performance is tuned in to, alone and unadulterated, before a brief silence prompts the coughs and shifting of audience, effectively dissolving the barrier between performer and audience so common in western performance.

The embed isn’t working; here’s a link.

Biliana Voutchkova - Seeds of Songs (Takuroku, 2021)

Biliana Voutchkova collages sound from field recordings, objects, voice, violin, and other instruments documenting a new approach to her listening and creation during the pandemic on the 31’ piece, Seeds of Songs.

I think the conditions of the pandemic provided a possible catalyst for listening perceptions, or at least an opportunity to become more deeply acquainted with the sounds of the home. I have always heard how the cottonwoods rustle in the wind, the coy song of the screech owl, the whine of the neighbor’s dog in its separation anxiety, our resonant wind chime but now I’m also aware of how the home frame creaks in the afternoon breeze, the calls of daytime wrens and jays, the particular timbre of a neighbor’s truck motor turning that leaves after I would, and, my favorite, the fan resonance of our HVAC system and its musicality. Being home more opened our ears to more sounds of the home. And the personal associations of home might have made these sounds more personal. There’s a throughline there. What could the collage of trees rustling, a whining dog, and air conditioning have in common? They’re home.

Something similar is at play in Seeds of Songs, though with more intentional soundings. While there is still violin - scraped, scratchy, plucked, and played beautifully too - there’s croaking groans, hymnic hums, throaty wah wah, coos, and choked whispers. There’s tapped metal resonating. There’s fluted, bowed, or scraped metal singing. There’s something rolling in a mortar. There’s a chain or a necklace jangling. There’s a clock or piano or bowl chiming. And there’s many more acousmatic textures. While these sounds might be presented as non-narrative, unrelated events, their juxtaposition might create a narrative and a throughline, and it is very personally Voutchkova. Her new approach of collaging these personal sounds, her voice and unintentional sounds and sounding objects with special significance to her, taps a kind of intimacy that cannot be conveyed by violin alone. This approach, while also capable of a broader timbral palette, is markedly diverse in cadence, intonation, and rhythm in ways I’m not sure is possible or conveyed as clearly with the violin. There’s something about it that says it is the sonic meanderings of sitting and listening at home. All of this is to say, I found it a welcome counterpoint to her violin work.

A couple of months ago we got a new bird feeder, and the birds have been at it. It’s spring. It’s rainy here. Things grow fast. But I was surprised to find that the many different fallen seeds had already developed a kind of soil, sprouted and woven together to form their own aggregate turf.

https://www.cafeoto.co.uk/shop/biliana-voutchkova-seed-of-songs/

Yan Jun/Zhu Wenbo - twice (Erstwhile Records, 2021)

Yan Jun and Zhu Wenbo collage sounds of voice, recordings, objects, instruments, and sine waves on the hour-long twice.

twice appears to take a game form. With the notes describing a kind of alternating time assignment, the sounds of a chess clock as pictured on the cover appearing throughout the piece, and what are presumably some rules spoken. But I haven’t figured it out yet. The patterning of layers can seem inconsistent, all four sounding configurations across both layers appearing around the midpoint, a clarinet and a dog distantly barking continuing through sequentially clocked segments when the expectation might be a change in sounding configuration when the clock is hit, though it’s difficult to track layers among these sometimes acousmatic sounds. The sound recognized as the clock begins to blur, sounding as if manipulated by hand, or its recording manipulated in time, or blending with percussion. The couplets of presumed rules, the first two words of which I can’t make out, leapfrog with similar but different meanings and that pattern breaks down: start > start > stop > stop > pause > create; time > duration > silence > silence > pause points > silence points. There is perhaps some time trick too, not just in the sound of the clock but rapid cuts in roomsound and the warped tones of recorded mandolin. As playtime does not often coincide with gametime in sport, so something feels incongruent here. Indeed, one of the other spoken moments I can hear is “for to make it slow, we have to move quickly.” I have a hunch that there’s more subversion of expectation and perception than a clear-cut game. It seems to foreground the absurdity of coaxing a linear narrative from non-linear time by making one tempting but perhaps not possible.

Thank you so much for reading harmonic series. If you appreciate the music and the words about it in this newsletter, consider sharing it as a method to advocate for the music and the people that make it possible. harmonic series will always be free but, if you appreciate the efforts of the newsletter specifically, consider donating. As always, readers are encouraged to reach out about anything at all, even just chatting about music, to harmonicseries21@gmail.com.