1/4

conversation with guitarist Cristián Alvear; notation from Theresa Wong & Ellen Fullman; reviews

Houston, Texas’ Nameless Sound performance series continues celebrating its 20th anniversary by diving into archives of previously unreleased sound, video, and stories from musicians with deep connections to the series. Profiles of Joe McPhee, Maggie Nichols, and Alvin Fielder are available and an exploration of “The Dialogue between the Aural and Visual” is forthcoming.

conversations

I interview Cristián Alvear, a guitarist and composer born and based in Chile and resolutely dedicated to the performance, premier, and recording of new music, releasing Michael Pisaro-Liu: E là Fora, Auralidad, Radu Malfatti: hensou, Michael Pisaro-Liu: an unrhymed chord, Radu Malfatti: shizuka ni furu ame, and d'incise: Appalachian Anatolia (14th century) just this year at the time of writing. Over video chat, we talk about the Chilean experimental music scene, listening, personal habit and institutionalization, interpretation, authenticity, repetition, and Guns N’ Roses.

Keith Prosk: How are you?

Cristián Alvear: I’m doing OK. How about you?

KP: Good good. You can hear and see me alright?

CA: Yeah yeah yeah. I can hear you fine.

KP: Perfect! Well, thank you so much for chatting with me a bit.

CA: No, thank you. I didn’t want to do the writing interview because it’s just too… I wanted more spontaneous responses to your questions.

KP: No, that’s perfect. I’m always down for any method that anyone else prefers. Whatever anyone else is comfortable with, I think it brings out the best.

CA: That’s great.

KP: So, you mentioned that you’re in the middle of some dissertation work right now. What are you up to there?

CA: Here at the PhD program you have to do an exam later in the fourth semester, which is in mid-October, actually. So I have to prepare for the exam. I have to reshape my project. And then I have to do some essays that those who are going to read my project are going to ask a few questions about. And I have to write a few essays regarding that. So, right now, what I am preparing is the project itself and some of the recordings that are requested for that specific project.

KP: Nice. Are you free to talk about kind of what project you’re tackling?

CA: Yeah! Sure sure sure. So I’m researching experimental music made in Chile after 2010. And so not only Chilean composers there is also - I don’t know if you know him - Jean-Luc Guionnet wrote a piece for me. When he was here, we worked together for awhile and then I went to France and we did an artistic residency together so we can work on the piece a little bit, on the composition itself. I haven’t played it yet, I’m just researching about the conditions of the piece. Because my approach to interpretation is performance as critique. So I’m drawing from Adorno’s and Benjamin’s critical theory in order to understand the conditions of each piece. In this case, it’s Jean-Luc’s and a composer called Santiago Astaburuaga.

KP: Ah, OK. He’s in the LOTE ensemble, right?

CA: Yeah yeah yeah. He’s the core director of the ensemble. It doesn’t exist any more, the ensemble.

KP: Oh no, when did it dissolve and why?

CA: 2018, I guess. We did some rehearsals in early 2019, but then, I don’t know if you know this, but at the end of the year in 2019 there was kind of a huge problem here in Chile. We had something called Estallido Social, so everything stopped. We had people on the streets and demonstrations - very big demonstrations - from October to January 2020. So everything stopped. And then the pandemic. No more ensemble work.

KP: Gotcha. OK. I understand you’re actually trying to build a scene in Chile for experimental music and foster appreciation for it. What are some of your efforts going on there?

CA: Well, mostly concerts. I work closely with Nicolás Carrasco and Santiago Astaburuaga, both composers. And we try to do concerts. Also, dissertations. In places not in Santiago, not in the capital. I’m from the south, so every time I go there - I haven’t been there in awhile now - but every time I go there I try to do some concerts and talk about experimental music. What it means to play, to interpret it, to realize these pieces. What is involved in the realization of this kind of repertoire. There’s a scene here - it’s a very small one - and it dates back to the year 2000 approximately. But for the people involved in the scene to do pieces, like written music, it’s fairly recent. I mean, not before 2010, I would say. Before that it was just like improvisation, and some sound artists also presented their work. We have here two big festivals for experimental music. One, it’s in the south, it’s called Relincha Festival. I would say that those are the efforts we’re making to showcase the work we’ve done with these pieces. For certain, to try to show people that there are other forms... you can do music in other ways, it’s not always a written score.

KP: So, I guess, what was the catalyst for that kind of scene starting in 2010, and what are some of the difficulties too in getting it up off the ground?

CA: Well, money, basically.

KP: Do y’all have government funding for the arts that you can access?

CA: We have, but it’s pretty traditional. We’ve made some efforts, presenting some projects for having some funds to do recordings. Nicolás now is working on a book. He did some translation of Manfred Werder’s writing. Some articles and papers. And both Nicolás and Santiago have PhDs on experimental music. Nicolás from a philosophy perspective and Santiago from a composer’s, also with philosophical implications but more based on his practice and his own compositions. That insert these kind of practices into mainstream academia and to also have funding.

KP: Funding’s always a huge issue, even here in the states. Are there any composers or performers that you want to shout out from Chile? Or any resources that international listeners can look into if they want to check out the scene?

CA: I can give you some names. Maybe later I can write it down and send it to you by email. But there is Edén Carrasco, a saxophonist, he’s very very good. He’s more into improvisation than any other thing; he does also written music scores as well. But mainly he improvises. There’s also Nicolás, he’s very important to the scene. Santiago as well. There’s Bárbara González, who’s an excellent artist. I don’t know who else comes to mind right now, but I can give you a list and some links to their work.

That list that came after includes: Christian Delon; Marcelo Maira; Sebastián Jatz; and Ervo Pérez.

KP: Narrowing it down more to your practice. Whenever I think about your efforts, I feel like you’re very dedicated to the premier, performance, and recording of new music from all niches of experimental music but especially the wandelweiser collective. So what’s the mission behind the music, or what propels you to engage with new music so deeply?

CA: Well, as you may already know, I’m a classically trained musician. I did the conservatory and then I did my master’s degree in traditional music called Classical Traditional Music. And in 2012, I was a little fed up with the contemporary music scene. Those pieces are very very difficult. You need to have the composer there most of the time because there’s an ideology of the authorized versions of the pieces. So if you work with the composer, it’s better. So I was kind of fed up with that and at some point I realized that all those pieces kind of resemble themselves. Even if I try to propose different approaches to those pieces, they end up sounding a little the same. So it was kind of routine musicmaking and I was fed up with that. So I knew Nicolás, because he’s a composer, also classically-trained, and so I started to improvise. I tried to do some concerts with improvisation and tried a few things here and there with that. I met Nicolas - I knew of him but I’d never me him - so we start talking and I tell him that I was kind of fed up and that I was bored with this kind of repertoire and he sent me the score for 24 petits préludes pour la guitare, Antoine Beuger. That was my first approach to wandelweiser music, and experimental scores actually. It was so different. It was kind of refreshing. And I wanted to do more. So I started contacting everyone from the collective, asking for pieces, and then in a period of five years I guess I recorded almost everything there is to record for classical guitar. At the same time I was doing other kinds of pieces as well. I was working with pieces written by Santiago and also contacting other people. The thing with wandelweiser is that it’s turning into something mainstream. There are many universities that are teaching about wandelweiser music, indeterminacy, post-Cagean music as Michael Pisaro would say. It was kind of the perfect time for me to engage in this kind of work. So it had a big echo in the academic scene. Also, I have the feeling that some of the venues, festivals were changing course a little bit regarding the repertoire or the kind of music they were programming at the time, so they started to program written music. So it was kind of a perfect time for me to do this. Because I am classically-trained, in terms of technical complications, it wasn’t that hard for me to engage with this repertoire. What was difficult was the conditions of these pieces, if we relate to my research right now. Because the implications in terms of performance and the process of realization of the pieces are so different. In a matter of degree. Not different that they are absolutely different. They are both contemporary music as a big frame for this kind of music. It’s just... they have the same chain, so composer, piece, written score, performers, performance, so it’s the same thing in that way. But there are implications that are very very different. For me, it was very interesting approaching these pieces in which I had to do the same job I was doing with contemporary music but having to have in mind all the time that these pieces involve something different. So that was kind of a challenge and I was completely drawn to it and, well, I still love doing that.

KP: When you’re looking at a composition to engage with and perform, is there a set of qualities or conditions that you’re particularly drawn to?

CA: That’s a difficult question because the thing is that I’ve come to realize that every piece of written music has an enormous amount of possibilities in itself. It depends on the performer, what to do with those. The problem for me is that, as there are performances that are not very thorough, there are also scores that are not very thorough. For me, what’s most important is that the pieces themselves present with a problem. A problem that I need to solve. And that problem doesn’t have to be an explicit problem, but there are many pieces… at some point I’ve received a lot of pieces to play and not all of them were interesting. In terms of this problem that I was looking for. To do a composition is difficult. It’s not just a matter of writing some instructions and then just giving it to the performer to do. You can do that, of course, and there’s a lot of that. But then we enter in an area of sameness. So there’s a lot of things that resemble a lot. And that is not only because performers create some habits regarding musical notation, so you read an instruction and immediately know what to do, but also there are composers that are not foregrounding these problems in the scores in terms of notation, etc. So also you have this area of compositions that resemble a lot and they don’t really present problems. But of course it depends also on the performer. You can find problems everywhere if you want. It’s not set in stone, it’s something that you have to look for. For me, personally, I like scores that present difficulties for me.

KP: Yeah, so your style… you strike me as a very technical guitarist… I guess there’s this perception of virtuosity as like speed, which is not what happens a lot in your music, but very technical in the sense that you do get into this problem that has to be interpreted, understood, and solved to produce a satisfying result. Would you be willing to share a performance or composition that you’ve had a lot of difficulty in solving that problem, or understanding that problem, and likewise, on the other side, are there some that you return to just for fun or kicks?

CA: Yeah, for sure. At first wandelweiser for me was kind of a big problem. Playing quiet is very difficult on any instrument. To have a good tone, projecting sound when you play very softly is very complicated. But there’s also another problem that - it’s not really evident in itself - the fact that you have to listen to what you are doing. When you are playing contemporary music, it’s very difficult to hear… for instance, if you’re playing in an ensemble, what you’re looking for when you’re playing the piece, you’re looking at the director for your entrances and he’s basically telling you what to do and what not to do. So you can do a very automatic work. It’s not everyone’s case, I don’t like to generalize on this subject, but it tends to do so. It’s the monologue of the orchestra. If you’re on the third row of the first group of violins, you don’t really hear the cellos, so you need a conductor. So the fact that with pieces that are very soft you are forced to listen in order to produce quality sounds, it’s something that is very difficult and philosophically it involves many layers of thinking. You have to do a certain process in which you have to comprehend the piece in a very different fashion compared to contemporary music. Of course, there is very soft music, very quiet music in contemporary music that also involves a lot of hearing. The thing is that when we talk about music, listening is something that you assume is always there. It’s impossible to talk about music without talking about at the same time listening. But the thing is that listening and hearing are two different things. And listening involves a high degree of subjectivity. And you have to understand and the process of understanding depends on the condition you already have. I mean, your culture, your education, what you understand as a musical sound. In the case of wandelweiser for instance you have to make a relation in terms of listening with the environment in which the piece is being played, so it’s very active. So every time I play a piece, it has to be a little different because I have to adapt the way I play to the environment, or what I am doing. In that regard, it’s not a fixed performance. I can study the motions, I can study the gestures, but I also have to engage in a very active listening, an active process of listening and understanding and be sensitive to it. So that’s a very big difference in terms of how you play and that also has a correlation with technical gestures. So you have to be able to play what you are hearing or make a relation, a connection between what you’re playing and what you’re listening at the same time. It’s pretty dynamic in that regard.

KP: So you were introduced to that from the get-go with wandelweiser? You would say that’s a relatively common occurrence across their compositions?

CA: Sometimes with wandelweiser music it’s pretty there. It’s something that I do. Also what I like to do with wandelweiser pieces… for instance, if I come up with a concept of listening, I can apply that to all of the pieces. But that’s another habit. So I have to reformulate every time I play some piece, I need a concept to engage. A very good example for me is Michael Pisaro’s Melody, Silence. You have different modules that you have to rearrange in order to make a realization of the piece and for me listening was not enough in that regard, I needed something else. I try to avoid reflexes in order to play. Even if it doesn’t show, it doesn’t matter for me. The thing is that I like the process. So the thing is for me to play a piece it takes a long time, because it’s not only playing the notes but I need to think about how I want to approach the piece. Because when you develop a habit of playing, you can of course play everything based on the things you already know and, if I think of the pieces as a way of reassessing what I know and try to come up with new things, I need to find problems. So concepts in that regard they are very very important for me to dynamize my own practice. Even if it doesn’t show.

KP: You do a lot to subvert your personal - at least automatic - language and approach a piece on its own terms. Do you find yourself developing a language between composers? Like, if you’re performing a Michael Pisaro piece, how much are you taking into the performance with you versus like an Antoine piece or a Radu Malfatti piece or something like that? Do you find yourself developing subsets of automatic languages almost, or is every single piece an effort to do something new?

CA: Every piece. I try to. Well, you need time for that. It’s not something you can do all the time. I don’t know... if I’m invited to a festival and they ask me to play with an ensemble, and I have just two days to rehearse, it’s kind of complicated. Because the process also involves writing a little bit and recording and listening and so I try to reflect upon the things I’ve already done, the things I write, etc. For me the main problem with musicmaking, especially with these kinds of pieces, is that you have a singular, particular piece that demands a particular, singular response to it. So for instance if you have an instruction saying make a long sustained sound. The first time I encounter that, with my guitar, the way I play, I can do this instruction in this way. I just do a specific technical response to that instruction. But if I’m lazy, every time I encounter an instruction like that I can do the same thing. Because it works. What I try to do is not to fix the responses. I try to take extramusical things into the process so I can change…. sometimes I don’t…. I make a choice, of course. But I try to reflect upon that and try to come up with something that is challenging to me. Otherwise, it is playing classical music again. In the way I was taught. The thing is, you can do the same thing with classical music. The music is very institutionalized.

KP: Would you say that the composers in the wandelweiser collective tend to take the same approach to their compositions, where each one is very singular and unique as well (coming from a listeners perspective that’s not necessarily intimate with the conditions)? Would you say they take a similar approach more often than not, where they try to make every single piece relatively unique?

CA: I don’t know. I don’t know. The thing is that why I don’t ask them… well, I can ask, we’ve talked about these things… but the thing is that I cannot assume that. Because if I do that, if I make my response dependent on that particular way of seeing music, basically what I’m reproducing is the same thing you do with classical music. When a composer has an image of the work they’re putting to paper, you need to relate to that original idea as thoroughly as you can. It’s something called werktreue and it was invented as a concept in the nineteenth century. So you can look for that as a condition as well, of course, but, for me, I only relate to the score. Or I try at least to only relate to the score. Because otherwise, you’re talking about style. And when you’re talking about style, you have standardized responses to certain musical notation. And that’s a very complicated question regarding wandelweiser, because you can instantly assume that wandelweiser is a style. You have the pretty field recordings with the super soft sounds and the sine tones and there you go, you have a wandelweiser piece right away. You can do that too. But I think it’s lazy to think of music like that. But as a performer I try not to be too influenced by the composer’s perspective towards their own music or music in general, so I try to keep a distance with that.

KP: I imagine these particular composers encourage that as well...

CA: I guess… [laughs] not really, not really...

KP: You mentioned before that wandelweiser was going mainstream, entering the academic world. Would you say that’s more on the positive end of mainstream, as in it’s getting advocacy and recognition in the right amounts, or would you say there’s some negative aspects attached to that as well? Or maybe even a kind of homogenization that might come with that?

CA: It’s difficult to say. As you might already know, Michael Pisaro teaches at Cal-Arts, Jürg Frey is constantly invited to contemporary music festivals. Here in Chile, for instance, in the university where I’m doing my research, they now have a course involving indeterminacy and experimental music and they teach wandelweiser music. It’s pretty recent. But these are signs that can tell you that it’s been absorbed by the mainstream academic culture. It’s good to do research, of course, I advocate research. I think it’s good for everyone to do some research from time to time. But for me the negative aspect is that... so, when you do research, what you’re trying to do is come up with a theoretical frame to understand something else, so in that way it’s interdisciplinary. You don’t think of music in musical terms because in that regard it’s not transmissible. I cannot tell you, I cannot write it, it is very difficult, if I do research of Takemitsu’s music and I give you a score, it doesn’t really say anything to someone that doesn’t read music, so you have to be able to verbalize that and put it into words. The problem with words is that you can fix meaning. So, you can have a very specific set of significance regarding notation, style, etc. etc. It’s always a danger with research in everything, not only in art. So, with indeterminacy, it’s kind of the core of experimental music or reading experimental music, specifically in wandelweiser for instance, it can be a danger to trivialize the way it should be played so it can be taught. And when it can be taught, it means that it’s already standardized and institutionalized. So that can also be dangerous to absorb this kind of music like it’s another piece of contemporary music. That can also be a problem. As I was saying, it’s a problem with everything. I love classical contemporary music from Japan - I play a lot of Tōru Takemitsu - and you can have a very standard approach to that music and do basically the same thing you do with a piece from the nineteenth century. Because it’s a way the guitarist plays and there are expectations towards what is supposed to be a guitar performance, etc. So you have a lot of fixed responses towards the music and the way it should be performed. There’s a prejudice regarding performers that we are kind of trained monkeys, you know. Because everything is written down, you have to do exactly what the composer says, but that’s not the case. So when you have a different version of the same piece, what you hear is the person playing the piece. And that’s very important because we all know what it is, but to ask yourself who is doing the musicmaking, it’s an entirely different animal, you know, a different way to approach music. It’s very important to have that, and fixed meaning creates reflexes and habits towards playing, so we are encouraging people to say we are trained monkeys in that regard. But we are not!

KP: So far in the conversation there’s been a constant push back on habit, and I feel like for a lot of people the reflex is, ‘well, improvised music is a good combatant to that.’ But what you often find is improvisers falling into their own personal idioms and really kind of doing the same type of music. So, I guess, this might be answering my own question, but would you say a blend of composition with a healthy dose of choice or indeterminacy is the preferred way to go for pushing into new directions in music?

CA: Yeah, for sure, for sure. The thing is that, well, classically-trained musicians, they love to play their instruments. You go there to study exactly that with that teacher and it’s super-important. So everything else, it’s secondary. Which is a danger in itself because it’s very important… if you’re not able to reflect upon your own practice, you end up doing the same thing all the time. You can develop intuition, very very strong intuition, and realize, intuitively, that you can do something else with certain music. But the thing is that after that - and not everyone does that - you encounter like a wall. And that wall is yourself. So the only way, for me at least - as I was saying, I don’t like to generalize and this is not a prescription for making music, it’s my approach to making music - the only way to go beyond that wall is to reflect upon your own practice in critical terms. So try to understand why I play the way I play, why I understand the music as I understand it, and what else I can do to render a piece of paper with musical notations into something else. And that is a process that is always complicated. And with musical education and institutions it tends to be standard, you know. The thing is, how can you teach music without doing that? You go and find a teacher and you are going to play some Bach. So she shows you the way to do the trills and the articulation, etc., and you mimic. It’s in our nature to mimic. The thing is that maybe you can mimic something else, or in a different way, it depends on your understanding. But, if you’re taught that this is the proper way to play Bach, well, there you go. You just do that.

KP: It seems like a fine balance between accessibility and trying to stay true to these concepts. One kind of side thing that I’ve encountered is that recording… a lot of these performances might not be conducive to the recorded medium. At the same time, the accessibility of recording is allowing someone from Texas right now to engage with someone from Chile about the music. So it seems important in communicating these concepts, but is that another tug and pull that you find there? Do you have issues with recordings at all?

CA: Yes and no. Yes because it can be easily understood as something fixed. So, most musicians, at least those I know, they would search for the recordings of a certain piece they have to play. So you have a fixed sound image of the piece before you even play it. That can be a problem. For me, that’s kind of the negative side. I can’t take responsibility for that, otherwise I wouldn’t do any recording at all. For me, a recording is just a photograph. It’s just the recording of a certain time, a certain period, and that’s why I like to re-record pieces. Because they are different. Because I change, and the way I play is changed, and now I’m playing electric guitar as well so I try to play the same pieces with electric guitar which is an entirely different instrument. It’s the same but it’s different at the same time. The thing is, what should I say on my own bandcamp? ‘This is just a photograph, it’s not the authorized version.’ But you have that. If you’re a classical composer, a contemporary composer and you do a piece for me, for instance, and I play it and I work with you and I record that and I publish that, then it becomes the authorized version because it’s closer to the original meaning. So we have a problem with the origin of things. Which is a lie basically. Because we cannot go there. How you can get to really know what was involved in Prelude from Bach? You don’t know.

KP: Yeah, those questions of classical authenticity have always been super annoying, even to me as an outsider.

CA: Yeah! And it is, for us as well. Because you conform, you tend to build, to shape your own performance basing your performance on someone else’s performance, because it’s authorized, the way he did it, the tempos etc. etc. and you have a lot of that and the issue there is that that’s something we do unconsciously. Because that’s the way music is taught to us. So a good performance, a good interpretation of a certain work is that which relates as closely as possible to the origin of the piece, which is unknown, all the time unknown. You cannot know. Because if you want to say something, you just write it, or you say it, you don’t use music for it. If I have to say to you, ‘give me five minutes, I’m going to the bathroom,’ I’m not going to do a score. To assume that from the start is just a mistake. But the thing is that we tend to relate to… there’s an obsession with the original. What’s close to the source? Which is an absurd search, you know? You can do a lot of research but what you end up with are very well-constructed problems or perspectives and that’s super-good, I like that, but to assume you are going to do the research and you are going to get to the bottom of a certain piece. That’s a complete lie. That’s very difficult to know. And we continue to do that. It’s a goal for performers, to have super-true interpretation. And that’s a construction, a social construction. Through which we see music. Music playing and recordings, etc. With high fidelity equipment for listening to music, it’s close to the original, etc. etc. If it’s close to original, we assume it’s good, but it’s something that is learned. We have learned to see music that way. So that’s a problem. That’s the problem with recordings as well.

KP: Yeah, you see a bias like that in music writing too... a lot of people still reviewing albums for instance, instead of, say, tracks or longer pieces because that’s the music writing they were taught... you know, the digital age is here, a forty-minute LP length kind of piece is not required but that’s still what people stick to.

CA: Yeah… I love long pieces!

KP: So I guess getting to your work, when I think of the music that you’ve composed, if I had to broadstrokes find some things, it tends to be played on the acoustic guitar and it seems to be concerned with repetition, and maybe it gives a little more traditional weight to sounding than silence compared to the wandelweiser composers and a little more love to the instrument over the environment, I haven’t heard a lot of field recordings in your stuff...

CA: [laughs] no

KP: Whenever you’re composing, what are some ideas that you find yourself returning to or do you have some goals with your composing?

CA: I spend a lot of time memorizing music, you know, so it’s very difficult for me not to… I’m unable to memorize something that’s not written. So when I play my own pieces, I just write them down. Otherwise, I would completely forget what I’m doing. That’s why I write them and it can be called composition in that regard. Also, paper allows me to reflect upon the things I do, because on paper I can do other stuff different from the guitar. But for the time I still am very concerned with repetition in terms of… the thing for me is the sound. Sound is a very tricky concept because when you are asked to do a sound, for instance for a score or whatever, in order for you to recognize that sound, you have to have heard it before. It resembles something else so again it relates to something that you already heard. There is a very interesting concept there called timbre. The timbre relates to the source, so when you hear a trumpet, you think of a trumpet; when you hear someone’s voice, you think of that person. Timbre, it’s very unique and it makes… you can recognize the sound. Of course, every time we hear someone speaking, their intonation is always different all the time. So you get a different perspective all the time when you talk with someone, they don’t usually do the same thing, sometimes you can even say that they are having some problems because of the tone of their voice, you are able to recognize some stuff. In a broad sense, you have sonority. I don’t know if that’s a word you use…

KP: Yeah, mmhmm.

CA: I like that word. It’s better for me to talk about sonority rather than timbre because timbre is just one part of sound. So sound in that regard, it’s a very interesting phenomenon. Especially when you are producing sound. Sound that’s supposed to be apprehended as musical sound. Because there’s always a question of what is music. I mean if you hear the silent piece by Cage, 4’33”, what you hear is actually something happening in the room. So there’s a problem with identity there because you know you’re listening to that piece by that composer but it doesn’t sound all the time the same. So, how do you recognize that as the piece? Recognition doesn’t always happen through repetition. Sometimes you need extramusical terms. For me, repetition involves those two ideas. Something that it happens all the time because when you sit in a room full of people waiting for a concert, you hear those sounds, but you don’t know that maybe that’s the piece, you don’t know it yet. Except if the pianist is there or the instrumentalist is there and conducts you to the fact that these sounds are framed in a piece, a time in which you have to listen. So repetition in that way is very tricky because you can say it’s the same sound but you know it’s not the same sound. It depends on how you perceive it. I started working with that with Seijiro Murayama, the Japanese percussionist, and we have two records with this concept of repetition and iteration. But for my own work, what I’m doing right now, the pieces I wrote for the guitar are strictly involved with repetition, very accurate repetitions, with some little variations. It’s difficult, it’s physically demanding to keep on doing the exact same thing, the same attack, etc., and after awhile you realize that it’s not the same sound at all, you start losing something else, and all the harmonics start to show, and even the attack, the fingernail on the string, you can start hearing differences in that. What’s especially important is frequency, we are taught to think of music in regard to frequency, but sonority is much more. That’s why you start listening to details, and it depends on the speakers you are playing the music through, etc. - certain things come to the fore. So I did those pieces in order to explore that sonically. How can I maintain this? How can I make repetition without being repetition? So you can recognize that something is being repeated but it’s not really being repeated because the rhythm is different and not only the way you play it but there are different lengths of the same chord, for instance, that I am repeating. It’s kind of a trickery, you know? Because there is something repeated but it’s not really repeated. Right now what I am also researching for my pieces is that if you have to… if I have an instruction saying that you have to do a sound, and this sound only appears once, how do you make that sound recognizable? Or what’s the length of a sound? Because sound is kind of a unit. For instance, you have an e chord on the guitar, you have multiple sounds sounding but you recognize that it’s a guitar chord, but that length is very short, but why not think about the unit that is super-long. How would you do that? Because you can think of those pieces like small sounds patched together but you can also think of a very big sound. With all its nuances and details, so how do you augment what a sound is?

KP: I might be mispeaking here but I feel like some of your stuff approaches melody but sometimes it’s spaced so far apart it almost becomes an unmelody type of thing. It’s playing with time I guess and the listener’s perception.

CA: I don’t really care about people’s perception regarding what I do. What I really care is to take my ideas and try to do the most with them. Because if I expect people to realize what I’m actually doing, I’ll just write it down. I don’t mind if someone understands something else, or analyzes my music in some other way, I encourage that in fact. I’m just responsible for the things I do, not the things others do with my own stuff.

KP: Yeah, I think that’s always important. Everyone’s perception is always going to be totally different, so there’s no use trying to cater to that.

CA: Yeah, I can explain, but I’m not sure if the explanation helps. When you were asking me about how we are trying to make this Chilean scene grow, one of the things we decided to do is not to talk before the concert - we do that after the concert. We gather... usually when I go to the South, I do concerts in a very “concert” venue, very small, I don’t know, 30-40 people max, I don’t explain anything at all, I just play the music, sometimes it’s very weird, especially for my parents. And then we talk. Otherwise, if I explain a little bit, I’m prefashioning the way people relate to what I’m doing. And I don’t want that. So after we can talk and we can discuss and if someone asks me, ‘what did you do,’ what I intended to do, that’s OK. I would like to think that I encourage people to do their own thing with the things I do.

KP: Going back to playing weird and how your parents perceive it, I know in Austin, at least it seems like, all other things being equal, performances with a guitar tend to draw a bigger crowd. Would you say - being a guitarist and performing the music that you do - would you say that you do draw a bigger crowd, or draw more confusion because of the familiarity of the guitar?

CA: Both! As in most countries guitar is very popular, a lot of people play guitar, so there’s that. People go there to see someone playing guitar. Then, yeah, the thing is that I’ve been playing in my hometown for a very long time, maybe twenty or more years, twenty five. So some of the people, my parents for instance, they’ve been through the whole process, you know, from playing classical music to playing this weird stuff and even doing concerts without playing any guitar at all, just radios and computer and stuff like that. So, yeah, sometimes they know… they don’t know really what they are going to listen to and they go there because they are curious to see what’s going on. Last time I was there I played with Phill Niblock when he was here, and then in Brussels a few times, and we keep in contact, so he’s been sending me pieces for me to play, of course with the electric guitar and stuff. But before that, having an electric guitar, I just did concerts with movies and sound and that’s it. No one’s on the stage, there’s only the big screen with the movies and stuff and the music’s super-loud and that’s it. So, well, I don’t explain. And then we talk. And then you see without explaining, people sometimes come up with the craziest ideas about what you did and what the music means. Usually when you hear something you always try to find meaning. And that’s very very… the things that people say to me sometimes after concerts, regarding what they thought or what they were listening what they are focusing on, it’s mind-blowing, you know.

KP: In like an absurd bad way or what?

CA: No, the weirdest thing that happened to me is that someone started crying at some point, and it happened to me twice, in different countries, with the same piece. That’s super weird. I played a Taku Sugimoto piece in Osorno one time and there’s a like teenager, I don’t know thirteen, fourteen, there was a girl there and in the middle of the piece she started crying and she had to leave the venue. And then, a few years later, in Taiwan, I was in a very small venue, and as I’m playing again the same piece another girl started crying again with the same piece and she also had to leave.

KP: Oh, wow. That’s awesome! Yeah, I try to make it clear that any interpretations that I provide are entirely my own and really just trying to acknowledge that I am trying to assign some meaning to it in engaging with the music because otherwise, you know, in talking to other people about it what would I say other than ‘listen to it, it’s good’ but, yeah, it can come up with some real dud concepts... I’ve gone through all my prepared stuff, but is there anything else that you would like to talk about?

CA: I don’t know. I don’t know. I guess we covered a lot of stuff, in one hour. If you want to talk about something else I’m up to it, I have time.

KP: Well, what are you listening to lately, other than I guess your own stuff that you’re performing right now?

CA: Well, I don’t listen to my stuff. Never. Unless I forget about it and then I listen to it and it’s a whole new experience. Otherwise, I’m just thinking, ‘oh that chord there, I should’ve played in that way,’ or ‘this is not well-recorded, I should’ve put the mics in a different fashion’ so I try not to do that, except in the process, or when I’m mastering or editing. That’s something that has also changed in my practice, I do my own editing and mastering. If I’m allowed to. Of course, sometimes labels, they want to do their own stuff and I don’t mind them doing it. Otherwise, I do everything. I do recordings, mic’ing, etc. For that I am very grateful to Makoto Oshiro, Alan Jones, Jean-Luc Guionnet, all of them taught me a lot of stuff. Very important stuff for the things I do. And it’s been, well... the first time you record yourself, it’s very strange. At first, in my case, I didn’t have technical means, like super-pro stuff in the beginning. Now I have pretty good gear and I’m very used to recording myself but at first it’s the same thing when you hear your voice for the first time. ‘Who is this strange person playing the guitar?’ ‘I didn’t do that’ ‘This phrase is off,’ etc. etc. Then I realized that what was happening, well, I had to get used to listening to myself, but also because I was expecting something that is not me, so I had to come to terms with the things I did. Because recordings, as we were saying a few moments ago, it’s just a recording of a certain period, something very specific, it’s not meant to… well, it’s supposed to last because you can go back to it but it’s not a definitive thing, it’s not fixed, it’s something that happens just in a precise moment and that’s it. So once I came to terms with that, it was easier for me to record and try different things. And also because I realized I was very dependent on the concept of the original and what is supposed to be and this is the ultimate version of something, a piece by Bach or whatever. Once I got rid of those ideas - that ideology actually, because it’s this whole set of ideas and ways to behave towards music - it was easier. So, I don’t listen to my stuff. I like to listen to… what do you think I like to listen to?

KP: Um… [laughs] if I had to guess I would say classical guitar. I don’t know, I wouldn’t… maybe, I don’t know, I’m not really feeling a techno vibe or a hip hop vibe or anything…

CA: Well, actually, I listen to a lot of heavy metal, a lot of rock n roll, I don’t know. Since I bought an electric guitar, I learned how to play the guitar with an electric guitar, so I played the things I learned when I was a teenager, you know. So Guns N’ Roses, Metallica, then I went to Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, Jimi Hendrix, stuff like that. Then I spent so much time listening to classical guitar, that I, of course I listen to a lot of classical guitar, but I never stopped listening to heavy metal, rock n roll, stuff like that, also things from here as well. I am a big fan of Mexican music like Rancheras and Corridos, you know, that’s pretty popular in the south. I love those. I love those. Don’t you get the wrong idea, not every Chilean listens to Mexican music for partying, but sometimes, with some of my friends, we do that. I’m a vinyl collector now. I just bought the first three albums by Black Sabbath, for instance. I’m trying to learn how to play “Paradise City” from Guns n Roses with my new electric guitar, which is pretty complicated. This is because of the pandemic, you know. I’m trying to learn the solos of all the songs I listened to when I was young, I wasn’t able to do at that time. Now with youtube and you can download the scores and you can see what’s going on, there’s a lot of stuff. If I had youtube when I was young, I probably wouldn’t have ended up doing classical musicmaking.

KP: [laughs] Yeah, just would’ve become a rock star

CA: I would have loved to. [laughs] It’s much more glamorous than being an experimental music player, no?

KP: Yeah, probably a bit more funding as well

CA: Oh, that’s for sure!

KP: Any kind of new metal that you’ve been enjoying? Or new rock?

CA: Not really, I’m just going to my teenage years. The thing is I also listen to a lot of classical music. Not guitar, I don’t like classical guitar recordings except a few recordings here and there. I’m a pretty big fan of Bach music and since maybe fifteen years ago there’s a Japanese collective of musicians, they are playing and recording most of Bach music and it’s just amazing. It’s really really really good. I love jazz as well. I don’t know a lot about jazz, but I like Coltrane and Ornette Coleman and those guys. I love The Necks if it’s something that enters in the jazz area. So, plenty of stuff I guess. And experimental music, I’m trying to keep up with new recordings and new releases, so I listen to what people send me, a recent release or something, so we exchange. So I try to stay up-to-date in that area, but with rock n roll it’s just old stuff.

annotations

annotations is a recurring feature sampling graphic or other non-traditional notation with context and a preference for recent work with recorded examples, in the spirit of John Cage & Alison Knowles’ Notations and Theresa Sauer’s Notations 21. As a non-musician illiterate in traditional notation, I believe alternative notation can offer intuitive pathways to enriching interpretations of the sound it symbolizes and, even better, sound in general. For many listeners, music is more often approached through performances and recordings, rather than through compositional practices; these scores might offer additional information, hence the name, annotations.

Other vital resources exploring alternative notation include Carl Bergstroem-Nielsen’s IM-OS journal and Christopher Williams’ Tactile Paths, each of which reference and link many other resources for this kind of notation.

All scores copied in this newsletter are done so with permission of the composer for the purpose of this newsletter only, and are not to be further copied without their permission. If you are a composer utilizing non-traditional notation and are interested in featuring your work in this newsletter, please reach out to harmonicseries21@gmail.com for purchasing and permissions; if you know a composer that might be interested, please share this call.

Theresa Wong

Theresa Wong uses cello and voice to explore the interfaces of composition and improvisation, acoustic and electric, sound and other media - especially the visual, and other interdisciplinary spaces. Wong also runs the excellent fo'c'sle label. These two scores and their accompanying sound, collaborations with filmmaker Jonathon Keats and Long String Instrument (LSI) innovator and partner Ellen Fullman, provide a digest of this distinctive blend in their performance process.

Theresa Wong - Xenoglossia (2010)

Xenoglossia is a composition for multitracked and live voice intended to accompany Jonathon Keats’ installation-ready short film, Strange Skies. Strange Skies serves as a kind of travel documentary for plants, which in their rooted nature don’t often have the capacity for travel. It provides a veritable tour of Italian cuisine by projecting the light from moving images of clear skies and cloud formations filmed across Italy onto plants’ foliage. It provides further sustenance to plants with carbon dioxide in using the voice. And it intends to shift the communication and audience of the performer from human to plant, with sound more akin to air and water than speech or singing, hence the title Xenoglossia, or speaking unknown tongues. Additional details and conceptual information can be found here. I found that the project encouraged me to appreciate plants as individuals, rather than species. However, though a plant might be limited in transverse movement, I imagine their sensitivities to constant change in soil composition, invasive and other neighbor species across kingdoms, surface elevation, and the volatility of weather and climate in a post-industrial world might make their lives more adventurous than they let on.

The notation for Xenoglossia consists of colored semi-cirles, the proportions of which are determined by the Fibonacci series that is often observed in the plant kingdom, and the areas of which determine the kinds of extended vocal technique used, their entry and exit times marked at the roots of each semi-circle. The air sounds - whisps, whooshes, sucks, and hisses - indicated by purple and alone from 3:47 onward or the purrs, coos, and fragmented song of the red bird sounds paired with the throbbing neanderthal ughs/eehs of the orange manmade sounds up to 0:11 serve to isolate and identify some of the techniques used. An activity for the close listener might be to then parse what techniques and processes are associated with noise and rhythm in the particularly dense section from 0:23 to 2:16. And to contemplate how the reflected and rotated intentions, with their own times and durations, correspond to the sound. Of course, time and duration are one dimension and this is a two-dimensional representation, so the listener might also wonder if the sound reflects the increasing and decreasing space beneath a given point on the curve or what overlapping areas of sound and intention might mean.

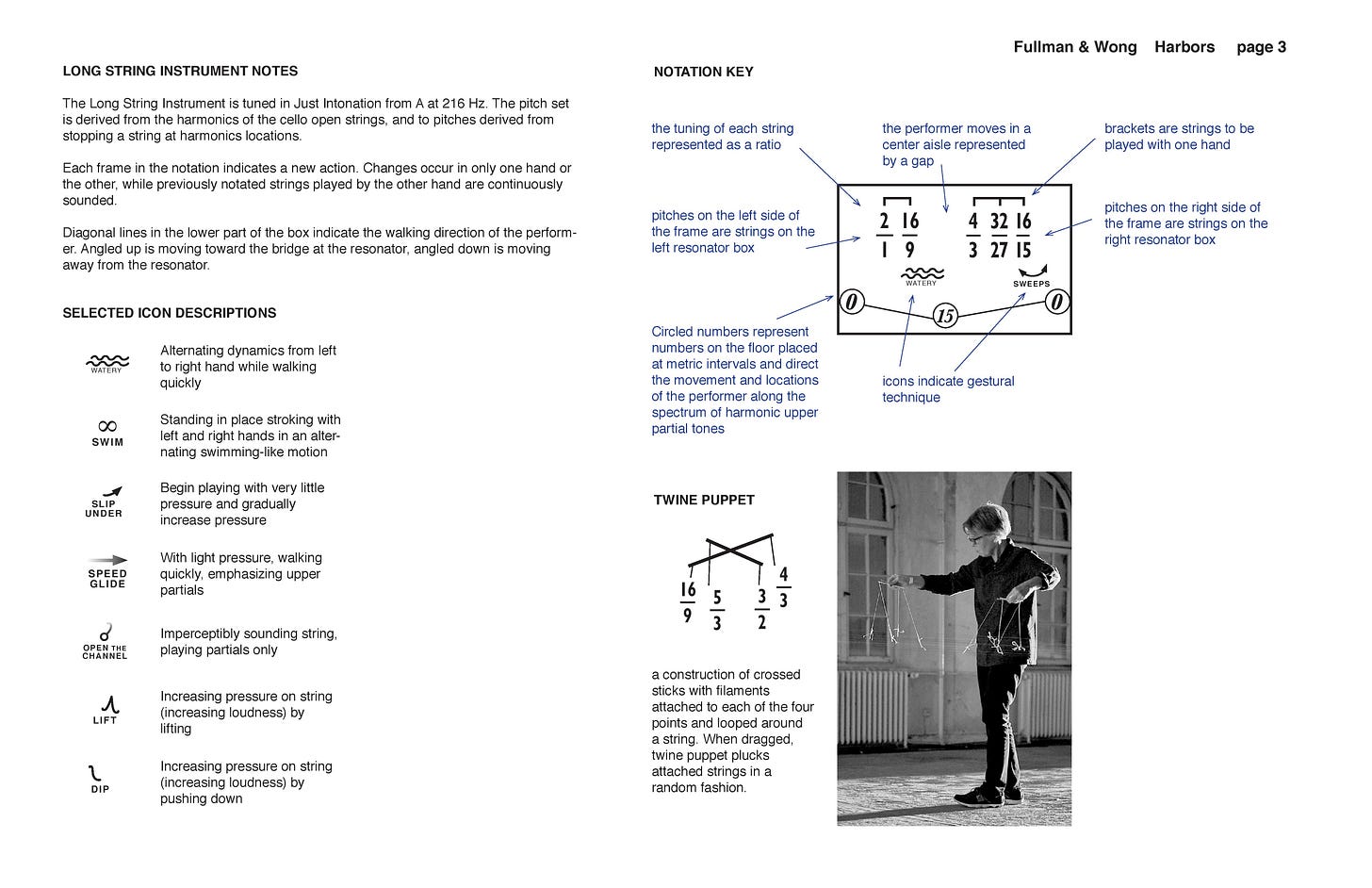

Ellen Fullman & Theresa Wong - Harbors (2015-2018)

Harbors is a composition developed through years of collaborative performance for LSI and cello with electronics that draws inspiration from “bodies of water that propagate change.” At first glance, the notation for Harbors is an incredibly intimidating, technical set of instructions. But I found its intuitive markers allowed me to compartmentalize my listening, visualize performance movement, and refocus and attune my listening to the moment-to-moment happenings.

The score is divided into three parts, as is the recording, and I might suggest beginning with Part 2 when first listening along with the notation to hear the character of unsampled cello, to distinguish what watery movements and the twine puppet on the LSI sound like, and to acclimate the ear before the more complex overlapping relationships of Part 1. Beyond parts, textual indicators locate you in the score with their apt descriptions: fog horns; blowing truck horns; beating frequencies; arco bounces; creaky dock; even the initially curious dancing satyr becomes clear when the cello emits those lively flute-like soundings. With these additional reference points, the LSI icons - sweep, zoom, swim - and their associated sounds are easier to locate and listen to, giving them greater clarity. The movements associated with them too. Having never had the opportunity to see Harbors or any LSI performance, and despite the numerous text descriptions and photos of them, the notation gave me a clearer sense of performance and its associated movements than ever before. Not just LSI icons but also the inclusion of left and right hand action, distance and direction of movement marked on the floor, and even string (roman numerals), location along the string (decimals), and whether a pitch is pressed (filled circle) for the cello. These markers and a strong visualization seemed to orient my listening and allow space for hearing more of the intricacies and complexities of this music than I had previously without the notation.

reviews

Nick Ashwood - Unfolding/Overlay (Inexhaustible Editions, 2020)

Nick Ashwood cultivates lush harmonic interactions with two bowed acoustic guitars in just intonation during the set-length performance of their own composition on Unfolding/Overlay.

Ashwood recorded two tracks and overlaid them unedited for this realization, though their organic interplay might make it impossible to tell. It’s my understanding bowed acoustic guitar can be especially quiet too, but this recording is satisfyingly loud, ensconcing the listener in its swells and waves. By nature of the bridge and neck’s flatness, almost all the arco is rich, warm chords. Languorous bowing cadences mildly fluctuate so one chord might ebb where one flows, at the rate of inhalation, exhalation, backwash, swash. They might ascend together for especially cathartic moments. Though a track may pause for a moment, there is no silence but rather a springing coil of dynamics. These simple soundings give rise to rich complexity, radiating rainbows of dancing harmonics that join and split to create a dense ecstatic polyrhythm of singing beatings and innumerable vibratory pulses cresting in ribbed crepuscular rays. And the beatings throb and soar in one track, each track, or from the interaction of both together, a sensual coupling of two guitar’s sound unveiled in their illuminated harmonics. A music of joy and frisson.

mattie barbier - Wolfgang von Schweinitz: Juz (a Yodel Cry) (self-released, 2021)

mattie barbier surveys the boundaries of just intonation vocal multiphonics for the trombone on the evening-length solo performance of the Wolfgang von Schweinitz composition Juz (a Yodel Cry).

Clusters of brief melodic phrases construct a weary, faltering fanfare that at turns leans bold and resolute, at turns plaintive and elegiac. The brimming sound catapults against the walls of the room, its collisions reverberating, testing the mettle of the bell in it furious shaking vibrations distorted totally in the farty low end. Clusters chained together sometimes by repetition of a tone. Sometimes by a sustained wind with a ghostly wail of sung multiphonics like an astral projection of the instrument. Sometimes by a moment of silence. There’s movement in the modulating vocal multiphonics, perhaps possible through switching registers between the bodily chest and the tinny head, yodeling, producing a strong sound that echoes and thrives in space that echoes. So while the ear might hear melodies first, the meat of listening is the harmonic interactions in the matrix between the lattice of soundings and singings, the willful spirit haunting and disintegrating in the space sometimes well after the breath has stopped. There’s actually another ghost in the room, a prerecorded accompaniment that might not become apparent until later in the performance, when clean and coarse soundings sound simultaneously. If purchased, the release contains a bonus track recomposed by barbier for two trombones in the absence of the prerecorded track and performed by barbier and Weston Olencki, originally released with brass sounds but mixed and mastered here.

Ko Ishikawa - “Divination at Dusk” (aurora argentea, 2021)

Ko Ishikawa showcases the rich harmonics of the sho on the cyclical sidelong solo, “Divination at Dusk.”

The track is taken from Ishikawa’s performance during the 2021 ToBeContinued 24-hour music marathon to benefit efforts towards ending tuberculosis. The structure is cyclical, building dynamics alongside melody, sustaining soundings to culture harmonics, decreasing dynamics, beginning again. Probably due to the instrumental associations with the culture of courts and castles, the cadence and pacing is stately and austere. The space, even during periods of quieter dynamics, is full, architectural, cathedral, with the high-pitched tinny ringings characteristic of the instrument taking shape and manifesting living pulsings like an installed organ brings its building to life. The deep strata of waves - some upper registers like circular saws on metal - are underlain by the mellifluous key soundings that make the melodies, distinct not just timbrally but almost offset as if one somehow could not be the source of the other. Though bristly timbres of high frequencies lend a certain abrasion, slow pulse and tempo, melody and harmony, and a swaddling spatiality make this a music of warmth and comfort.

Guillaume Malaret - Élémentaires du combat (Le Cabanon, 2021)

Sound artist Guillaume Malaret crafts dense and dynamic electronic environments with recordings from the places of their childhood on the concise, 25’ Élémentaires du combat.

Its two tracks split the time evenly. “Fissures, Appel” layers several symphonies of summer night sounds. The chittering, chirping, calling, and clicking of bugs. The quick pulses of these layers lend quick movement, so too do relatively rapid fluctuations in dynamics of certain layers that interweave them, sometimes several dropping out, though rarely to total silence. These drops, together with something like a chugging motor for off-kilter low-end rumblings, some glitched cuts, and later an eerie melody underlaying a UFO pulse, signal sensibilities akin to dub techno, complimenting these nocturnal creatures with what is often perceived as a nocturnal music. The blend of natural and electronic sound contorts the source, and I might wonder if some bugs might actually be plastic wind-up toys or shakers, or if these might all be natural, though manipulated sounds. The overall track form is progressive, rather than static or circular. “Brises, Soulèvement” uses similar structures and techniques. But the sources are now wind - the crash of gusts against the microphone, howling breeze - and water falling and running and springing and bird songs, crow caws, and owl hoots and wind chimes and clanging bells from the necks of sheep or goats or cows. Drops are sometimes signaled by a kind of airplane seatbelt sign sound. The track progresses to a cathartic quasi-spiritual organ-like throb, harmonics pulsing and beating, with a seemingly sung howl and something like shimmering cymbals. As if to make clear how humans might mimic wind in music. Indeed, both tracks strike me as expert reconciliations of the natural sounds that shape our memories and the music we learn and to which we form personal connections.

Sergio Merce - Dragón neón (SELLO POSTAL, 2021)

Sergio Merce does an especially electric rendering of his characteristically cyclical compositions and integrated system of synthesizer, ewi, and microtonal saxophone on the six-track, fifty-minute Dragón neón.

Accompanying the release is a particularly poetic musing translated as

“The ruminating mind repeats and stays still, repeats, hiding the other side. Sometimes it quiets down and through the cracks we see something. The dragon rushes over the flat ground curving space and flies low over open water. Beyond there's the ground.”

recalling Merce’s brief notes from previous releases that put a scope on the fine line between thinking and being and meditating and doing. Trying not to butcher the intention with interpretation too much, I imagine the dragon as a kind of foil to the mentally-tethered human. Wise and intuitive in its years. Its power not just from its mass but from its breath, transforming the air to something else, like a saxophonist. With the gift of exploration and observation in flight. Here choosing to move close to the natural world and towards open water and its greater fluidity closer to air. These characteristics might be close to the ideals of Merce’s music. With neon an apt adjective for the electrified air that’s so emphasized on this release.

The corporeal mass of this music hits in the first seconds, hastening and slowing fan resonance undulations weighted towards a doomy low end and so heavily distorting the air with its momentous gravity as to simulate a low-flying jet, nosediving and rising again, accompanied by a kind of overblown organ breathing fire. Beyond the deep dubby booms, crackling distortion, and synths, bass drops, drop outs, and beating clicks occur throughout, with a glitched aesthetic particularly prominent in the crashing modemsong in the first moments of “Vuelo raso” and the rhythmic substrate of clicks, cuts, bleeps, bloops on “Suelo llano.” The characteristically clean, smooth multiphonics of the microtonal saxophone are still foregrounded on a couple tracks, its multiphonic polyrhythmic pulsings simultaneously attached and detached or divergent to distorted crestings on “Mi mente toda es un insecto,” its soft purrs, muted sustained calls, and glassy refractions the core of “En aguas abiertas.” But the acoustic and electric elements are not always so distinct, and more often the sources of sounds are blurred and contribute cohesively and complimentarily in sometimes indistinguishable ways in this integrated instrumental system. Like with a lot of Merce’s music, it suspends in such a state as to make cyclical compositions feel progressive. But the circle appears to begin again - and maybe the man has glimpsed their dragon - as “Soy un extraño” nearly reprises “Espacio curvo.”

Panomorph - Panomorph (full body massage records, 2021)

The guitar ensemble Panomorph appear to explore harmonic interactions and perceptions of melody and harmony through electric and acoustic means on the three pieces of Panomorph.

The nearly half-hour “Transmission,” composed by Wong and performed by the full ensemble, is an alternating cycle of droning and picking. Electric sustain with string noise form phasing polyrhythmic pulses that accelerate and slow and combine for throbbing beatings, with dynamic variation in the number of guitars sounding at a given time, without silence. The discrete twang and lingering chiming harmonics of seemingly acoustic picking punctuates the drones with unmelodies, the duration between plucks distant enough to nearly frame them individually but rarely so far apart that their hanging harmonics allow silence. And, for a time, the sustained soundings stop. During which a hyperawareness of space might occur, where the various discrete tones illuminate and fade around the room like fireworks in a night sky. A kind of brief bowing signals the return of electric drones, which, after a three- or four-note melodic marker, soon resume alone without their accompaniment from pickings. And the cycle completes once more. My ear is poorly attuned to pitch and I have poor listening memory, but I suspect some cleverness in the relationship between plucked segments, as if each note in a segment is a part of a common chord or maybe each segment is a similar melody, and especially between the arrangement of sustained soundings and discrete pickings, maybe each consisting of the same pitches but translated, like a packet of chords transmitted through a long electric telephone wire before manifesting again on the other side as an acoustic strum. The eleven-minute “Replacement II,” composed by Kudirka and performed by the full ensemble, hones in on the undulating electric sustain and string noise, adding mirrors of feedback and tremolo picking for more of a chirp than a hum in the waves and more direct, forward, propulsive action, each of which lend a gritty and aggressive engagement compared to a sort of measured detachment that might suffuse the rest. The brisk eight-minute “Separated Harmonies,” composed by Wong and performed by Keller and Wong, hones in on the acoustic plucking. As in the similar segments of “Transmission,” the space of the room is apparent though less dimensional with just two points. Mellifluous chords, or maybe just a single note ringing its neighboring strings, sound, separate enough that the parts of their melody might again be framed individually, their harmonic glow diffusing in the air. Just before silence overtakes a sound, the next one appears, leapfrogging to form a chain, as if to elucidate that though these sounds may be so distant as to suggest they are unconnected they are indeed a continuous melody or harmony. Since “Replacement II” and “Separated Harmonies” are like details of “Transmission,” I wonder if those two tracks might share something translated between them.

On this release the Panamorph ensemble is: Wizard Ashdod; Hannes Buder; Margareth Kammerer; Beat Keller; Joseph Kudirka; Brett Thompson; Eric Wong.

claire rousay - a softer focus (American Dreams, 2021)

claire rousay arranges an especially cohesive, particularly musical statement synthesizing her experience as a percussionist, a recording artist, a confessionalist on the six-track, half-hour a softer focus.

For some time, rousay has demonstrated an uncanny ability for illuminating the throughline of disparate found sounds in their juxtaposition, but here overtly links tracks with continuing sounds - except tracks three and four presumably to neatly split an LP - asking the listener to interpret these tracks as an explicitly cohesive statement. While tapped cymbals and kick drum appear, the discreet pulses of movement parallel to the kit from her early work are supplanted by those from the subtle swells of sustained synthesizers and strings punctuated by bittersweet piano melodies and the natural cadences of layered traffic and voices and water and other recorded movement. Combined with indistinct autotuned voice, it strikes me as a recognition and progression of the emotive power of the last half of Kanye West’s “Runaway,” the catharsis of its instrumentation heightened by not knowing the words but in the believing of its confession too hard to speak granting a heavy gravity to every rise and fall in intonation. The acute awareness of intonation is made concrete when, amid a relatively rare non-solo record with friends in which the only clear voice is a conversation with a friend, a voice yields “my friend!” above a braked and turning truck motor, a contrary signpost of a word more frustrated with stopped traffic than elated by a relationship and whose only true meaning is in its intonation. That one clear conversation features another person hesitant about sharing more of their personal life on social media, who rousay convinces to keep a personal post up, a kind of affirmation of the power of confession. As if to capture in miniature her development so far, which appears to have mined sound for its emotivity and found that sometimes nothing conveys quite like speech but that that’s hard too, there’s a moment in “stoned gesture” where rousay nearly builds resonance with tapped cymbals, stops, lights a cigarette after several clicks of the lighter, exhales, pauses, and begins half-singing in heavy autotune.

Andy Stott - Never the right time (Modern Love, 2021)

Andy Stott continues crafting their distinctive ambiance of bassed-out club beats and Lynchian ballads on the nine-track, LP-length Never the right time.

Its songforms might appear less knotted, its structures less dense and densely-layered, and even Alison Skidmore’s airy quavering half-crooned half-whispered cradle songs less cut up, but the intricacies of the essential elements that make Stott’s music engaging are illuminated because of it. Expert sound design still makes Stott’s work the high-water mark in corporeal electric low end. The isolated chitter and hiss of cymbals evokes an impulsory anxiety like the bodily response to a snake rattle. The fulcrum, “When it hits,” provides a detail of the blend of acoustic and electric interactions developing in Stott’s work, hammered piano chords and their collateral jangle radiating harmonics that smoothly mesh with hymnic synths and from which reverbed pulses coalesce to create a polyrhythm of waves - this is not a concern or technique characteristic of a music so often shoehorned into techno’s various subgenres. Neither are the natural rhythms of the motion recordings, sounding like a sonic drawing, at the beginning of “Don’t know how.” While the omnipresence of a cathredelic synth substrate and heavy-handed reverb might become fatiguing, there’s new ingenuities in the arrangements, like the half-minute of sustain at the beginning of “Dove stone” that’s as tense and unsettling as extended silence in the context of this often mercurial release. And while the phasing, longer loops of stumbling bass arrhythmias seem to have given way to more foot-tappable, forward, sometimes vaguely latin beats, there’s still a compulsion to move from their undeniable energy. And with less vocal manipulation than ever, Skidmore’s words have never been so intelligible, allowing another dimension of possibilities in the music and making these songs the most immediately emotive yet. Especially when paired with a strong sense of nostalgia, established with a mood of decayed noir and the sharp timbres of retro synths, but enhanced by gestures that recall a past that feels close to this music, the melancholy island post-punk guitar of Bernard Sumner and their acolytes on “Away not gone,” the “Midnight Request Line” flute arpeggios of “Repetitive strain,” the stuttering rave crescendo like “Truant” in “Answers,” the “In the Air Tonight” variations of “The beginning” and “Hard to tell.” Raveled booming rhythms are probably what draws a lot of ears towards Stott’s music, but disentangling them refocuses attention to the depths of other aspects in Stott’s signature sound.

Vladislav Delay - Rakka II (Cosmo Rhythmatic, 2021)

Vladislav Delay forges dense, animate polyrhythms with a harshness akin to the purifying violence of the arctic environments that inform the music on Rakka II.

The volume is loud. The tempos are fast. No silence or rest. Thick strata of diverse distinct whirring pulses dizzy and numb. Their shifting dynamics - and dropouts - and beats and timbres an impenetrable dynamo that pushes the ear towards the select layers higher in the mix that often alternate in some sequence though in volatile durations. It’s hard not to relate the music to the arctic environment referenced on the cover and in the notes around the release and to the critical struggle it hefts upon the body. Its noise the turbulent disintegrating shear of arctic air along the wind-whipped ear. Its arrangement the clarity of cold wilderness elucidating a stream-of-consciousness alternating among ruminations, survival, the booming power of the pulse in constricted vessels. The only shelter might be the relatively warm hum and purr of “Rakas,” or the radiating pulses from deep throbs like some sun among the dark shade of “Rapine.” This music is harsh. But in its abrasion it humbles and cleanses the ear to make clear the basic elements of how a listener might bear something they could not dare to understand in the grandeur of its nature.

Nate Wooley - Mutual Aid Music (Pleasure of the Text, 2021)

Nate Wooley cultivates a performance environment of dense, eclectic, social chamber music for eight musicians on the eight-track eighty-minute Mutual Aid Music.

I wrote a context for Mutual Aid Music for The Free Jazz Collective gathering some history, conditions, and concepts of the music. And it seems like that approaches the extent of what I can write about this music at the moment, its sprawling density and complexity particularly resisting the reduction of encapsulating its sounds in a some words. I can say that it feels like chamber music, soberly measured even in its most manic moments. Though the musicians playing this kind of music doubled, it is never overcrowded, and the listener might question whether all eight musicians appear in all eight tracks. And in that way - sometimes sporadic contributions reflecting the pause of listening, contemplating, choosing an appropriate response - it sounds like a conversation, and so do its meandering progressive forms with tangents tethered to what came just before but always moving towards something new. It feels familiar to the music of Battle Pieces, and I recognize some of the material - the canned-air ksch ksch from Battle Pieces 4 that appears on “Mutual Aid Music IV” springs to mind - but again, like a conversation of even the same material, the music is revitalized by new voices and the new perspectives of a new time from the old musicians. While I have my hunches on who plays the framework and who plays freely for each concerto, based on time played, repetition, and assumptions from context, the roles of performance are largely imperceptible. Extended techniques color structural elements and repetition lends rigidity to textural contributions. Every aspect of Mutual Aid Music is so thoroughly integrated and acted upon that it truly sounds like a community music.

The performers of Mutual Aid Music on this recording are: Sylvie Courvoisier (piano); Russell Greenberg (vibraphone and percussion); Ingrid Laubrock (saxophone); Josh Modney (violin); Matt Moran (vibraphone); Mariel Roberts (cello); Cory Smyth (piano); Nate Wooley (trumpet).

Thank you so much for reading harmonic series. If you appreciate the music and the words about it in this newsletter, consider sharing it as a method to advocate for the music and the people that make it possible. harmonic series will always be free and accessible without a sign-up or sign-in but, if you appreciate the efforts of the newsletter specifically, consider donating; donations offset the cost of the newsletter, determine stability and growth, and, in the event it becomes a collaborative effort, will be used to provide contributors a respectable fee. As always, readers are encouraged to reach out about anything at all, even just chatting about music, to harmonicseries21@gmail.com.