1/2

conversation with saxophonist Sergio Merce; notation from John McCowen; reviews

Welcome to the second newsletter of harmonic series. Since sending out the first, I’ve become aware of some great resources that I’d like to share up front.

Nameless Sound, a performance series organized by Dave Dove in Houston, Texas, USA, is celebrating its 20th anniversary throughout 2021 with extensive monthly features on musicians and musical topics with deep connections to the series, including previously unreleased recordings, videos, and photos. The January edition spotlights Joe McPhee; the February edition covers Maggie Nichols; subsequent editions intend to feature Alvin Fielder, Pauline Oliveros, the dialogue between the aural and the visual, and yet to be determined musicians and topics. I’ll provide brief monthly updates on the project through 2021.

Daniel Barbiero made me aware of Carl Bergstrøm-Nielsen and Jukka-Pekka Kervinen’s IM-OS (improvised music - open scores) journal, which gathers insightful perspectives on alternative notation for improvisers from the editors as well as practicing composers and performers, with lots of great pictures. I’ll include this as a resource link in the annotations portion of all subsequent issues.

Similarly, Robin Hayward made me aware of Christopher Williams’ doctoral dissertation on alternative notation for improvisers, Tactile Paths, which is a modular website with a friendly, easily navigable interface and its own robust suite of resources, including recordings, videos, and pictures. I’ll also include this as a resource link in the annotations portion of all subsequent issues.

Thank you so much for reading. Happy listening.

Keith Prosk

conversations

I interview Sergio Merce, born and based in Buenos Aires, Argentina and probably best known for playing the microtonal saxophone he created about a decade ago. Over email exchanges, we talk about the foundations of his practice, from instruments to concepts to influences. Significant insights include experiencing music as an alternate reality and striving not to be, but to do. Sergio’s responses are lightly edited to flow for English-language readers.

KP: For some time now, much of your music has featured a microtonal saxophone you created, which is an alto with the keys replaced with fluid taps. In a recent video, I think the bell was even removed. Could you discuss the evolution of this instrument? What encouraged you to explore taps and what do they make possible that keys don't? How has the instrument changed through the years and why?

SM: I was exploring multiphonics in my tenor sax for many years, and at some moment I started to think about the idea of exploring it in a saxophone that let me open the keys gradually; that's the basic idea about this instrument. In a "normal" sax you have only two positions, open or closed; the taps lets me open each hole gradually and also, as I don’t need to have my fingers on it to keep a position, I can make any combination. Finally, I removed the bell some months ago just to make it more portable.

KP: A good bit of your work features electronics too, though it’s unclear to my ear if the electronic waves are separate, electroacoustic manipulations of the microtonal saxophone, or a combination. How do electronics fit in your practice? And what are you trying to do when using them?

SM: I think I have played the microtonal saxophone live only once without amplification, and I play it that way on my record three dimensions of the spirit. In fact, I have used two freeze pedals with the sax from the beginning. I conceive the whole set as one instrument; electronics are not separated from the sax; I play all at the same time, even when I record. When I started playing extended techniques on my tenor, I started trying to sound like electronics; I don't think of the microtonal sax as an acoustic instrument.

KP: Yeah, I'm aware of the tenor saxophone from at least three dimensions of the spirit; more recently, on especies de basilea and en lugar de pensar, you've incorporated an ewi (electronic wind instrument) as well. Are there particular things you’re trying to make possible when choosing these instruments over the microtonal saxophone? Or, what encourages you to choose one over the other for a given situation?

SM: I never know what I’m going to do when I start a new piece or a new record; everything starts with explorations, then I take notes, and so on. The same happens with the instruments I use; I am always thinking and searching for new ways of producing sounds, then I explore new devices and decide if I like it or not and what to do with that. My first approach to electronics was through an old cassette portastudio that I played without tapes, just using circuit sounds and touching the head with metallic objects, then I started exploring synthesizers. The ewi is a synth that you play blowing, so it was a very interesting option for me to explore. I play an ewi 4000s that lets me program my own sounds. I only play ewi in the trio with Catriel and Tomás, then I use it sporadically, like a little intervention on en lugar de pensar, but I like the instrument and maybe I will use it more in the future.

KP: This feeling of unity in your instrumental approach seems reflected thematically in the few words around your work (be nothing, circular, continuous, pendulum, dimensions of the spirit, even your cover photo for especies de basilea). To me, the more visual words encourage an interpretation like a line is a wave is a circle in different understandings of time and space - a unification of elements usually perceived as different. Especially when paired with the contemplative character of your music, these themes evoke something like a (I’m hesitant to put a name to it but) Zen spirituality. What wisdom or concepts do you hope to reflect in the music? And how has the music developed your wisdom?

SM: Music is a kind of meditation, in the sense of surrounding you with a different kind of reality. We are always surrounded by sounds from everyday life. Music replaces that reality for another one that lets you see inside. It is like an invisible mirror. My intention through music is to make listeners stop thinking, to disappear, to stop being afraid to be nothing. We are always trying to be this or that, a musician, a writer, etc. I think that we should try to just do, and not to be. I play and compose music, I'm not a musician. You can find a relation between this idea and Zen, I have nothing to do with religions, but it’s ok.

KP: While I’m aware of Pampa with Catriel Nievas, it seems like most recordings with the microtonal saxophone are solo. Is there something about your practice that makes it difficult to collaborate? Is it a byproduct of a smaller creative community with compatible practices in Merlo? Or something else?

SM: I used to play with a lot of musicians in the past. Some of them went to live in other countries, like my friends Lucio Capece and Gabriel Paiuk, and some others continue playing the kind of music I stopped playing many years ago, more close to free jazz or noise. Anyway, I like playing solo a lot. I like working alone in my home studio. I find things that I would not find any other way. Then I play with musicians I feel more close to in musical terms.

KP: What, musical or non-musical, has inspired your music, especially now?

SM: There is a lot of art that has influenced me, but just to name some, I can say John Coltrane, Luis Alberto Spinetta, Carlo Gesualdo, Bach, Andrei Tarkovsky, Ingmar Bergman, Robert Bresson, bands like The Cure, Depeche Mode, My Bloody Valentine, Joy Division, Cocteau Twins, Japan, and I can continue saying names, but now I am listening to little music, maybe music from friends and musicians who share their work on internet.

KP: That's all that I had prepared, but is there anything you would like to discuss, add, or shout out?

SM: No, I think it is ok.

annotations

annotations is a recurring feature sampling graphic or other non-traditional notation with context and a preference for recent work with recorded examples, in the spirit of John Cage & Alison Knowles’ Notations and Theresa Sauer’s Notations 21. As a non-musician illiterate in traditional notation, I believe alternative notation can offer intuitive pathways to enriching interpretations of the sound it symbolizes and, even better, sound in general. For many listeners, music is more often approached through performances and recordings, rather than through compositional practices; these scores might offer additional information, hence the name, annotations.

All scores copied in this newsletter are done so with permission of the composer for the purpose of this newsletter only, and are not to be further copied without their permission. If you are a composer utilizing non-traditional notation and are interested in featuring your work in this newsletter, please reach out to harmonicseries21@gmail.com for purchasing and permissions; if you know a composer that might be interested, please share this call.

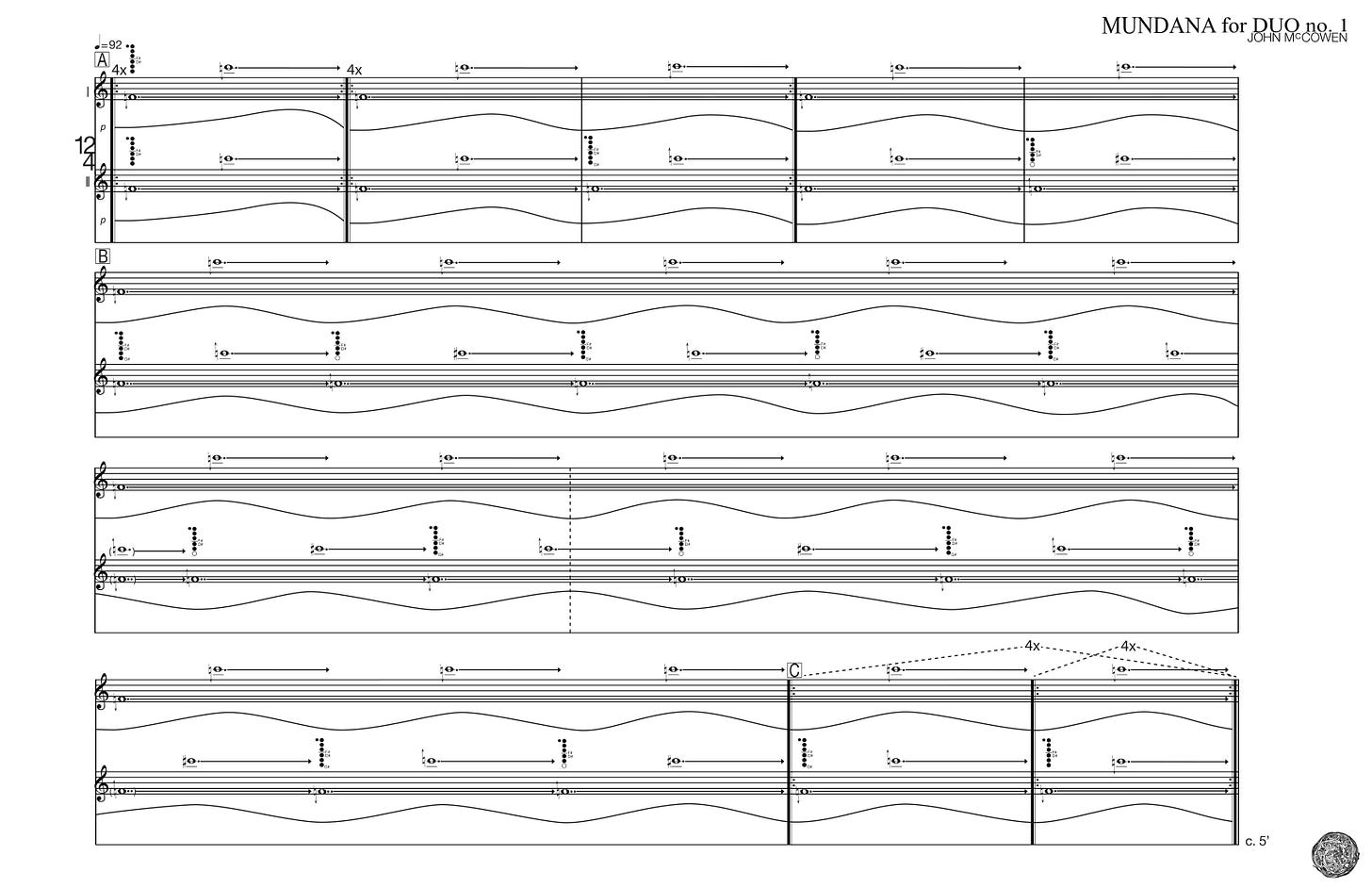

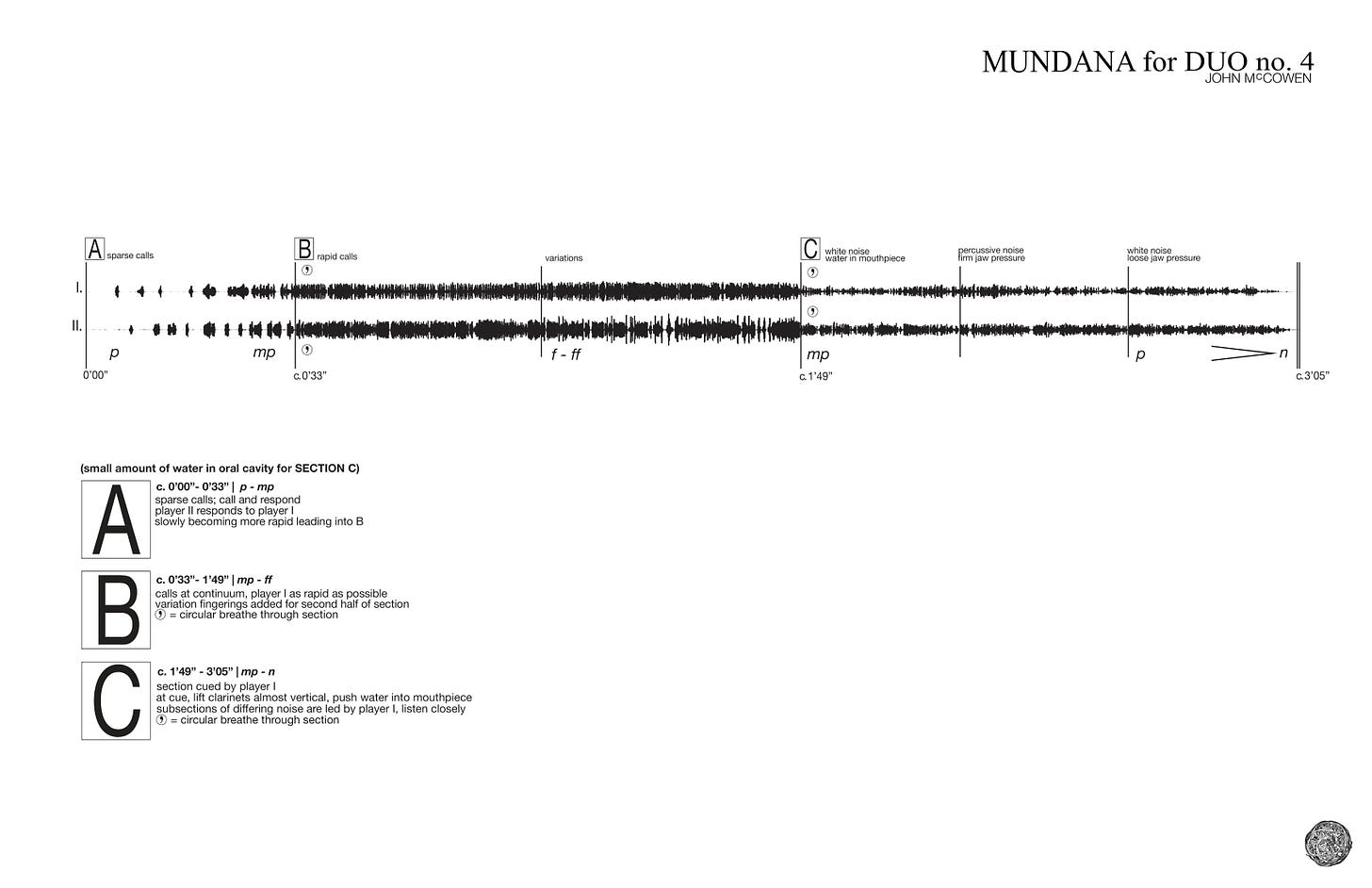

John McCowen - Mundana I & Mundana IV

Both performance examples from Mundanas I-V by the composer and Madison Greenstone. John McCowen rigorously explores the acoustic possibilities of the clarinet family. The record from which these compositions come, the two recordings from his 2020 ISSUE Project Room residency, and now the freshly released Robeson Formants in particular are recommended listening and among my favorite earworms.

Mundana I is a 2014 composition for two Bb clarinets. It is a phasing piece that provides a graphic indicator to the performers for one to successfully phase out of and back in to the other, movement heightened by the direction for performers to position themselves at a distance sufficient to produce a stereo effect for the listener. When listening to the performance, the harmonic beatings are so alluring that the phasing of primary soundings may go unnoticed. I found that having some information from the notation drew my ear back to the primary soundings, the structure of which I could then try to tie back to the slowing and hastening of the pulse in a more meaningful way.

Mundana IV is a 2017 composition for two Bb demi-clarinets. Direction includes a selection of possible fingerings, a diagram of how to cup the bell with the hand for calls, and a text description of how to use water in the mouth, which lends a source to these perhaps otherwise acousmatic sounds. The wave graphic gives a firm sense of dynamics, density, and duration. It also encourages a close listening exercise to identify sections without an approximate time marker, like the variations of the jungle canopy calls and the changes in jaw pressure while the mouth pushes water into the mouthpiece.

reviews

Stephanie Aston & Davið Brynjar Franzson - voice fragments (Carrier Records, 2021)

Davið Brynjar Franzson’s composition for live electronics and voice, voice fragments, performed by the composer and soprano Stephanie Aston on this recording, blurs sonic sources and the boundary of music between the interstices of fixed form.

Sounds fade in from silence at the beginning; sounds fade out to silence at the end. For a few minutes on either end, a mix of field recordings, found sounds, and faint electronic manipulations exist without the voice, and they are present through the duration of the performance. The static of recorded silence, or wind; the swoosh and whirr of traffic and overhead airplanes, or wind; white noise undulating, or ocean waves breaking; a menagerie of bird calls, with new tweets, hoots, whoops, and chirrups introduced like soloists, high in the mix, throughout the performance; and an occasional low end electric hum that can throb. The voice is only “aaahs” of various frequencies, sustained but with organic oscillations. Though not exact to the second, the duration of vocalizations are 20 seconds. The duration between clusters of vocalizations is more variable, between 0 and 60 seconds. In the simplest form, the voice sounds for 20 seconds, is silent for some time, then sounds again for 20 seconds. But vocalizations are often piggybacked with others of a different frequency. Peak vocal density occurs around 9, 22, and 30 minutes, with as many as eight vocalizations stringed together, which seems to align with the score on the cover. Things get interesting as the clarity once separating voice and electronics gets fuzzy. It’s unclear to the ear if individual vocalizations are mimicked, played back, or electroacoustically manipulated, or if electronics extend or even replace vocalizations, but I suspect a combination is used in the piece. The ambiguous relationship of voice and electronics summons questions of origin common in the blurred boundaries of electroacoustic music. The structure of framing it in field recordings and silence invokes the false binaries of music and non-music, sound and silence.

Daniel Barbiero - In/Completion (EndTitles, 2020)

Contrabassist Daniel Barbiero exhibits the collaboration of composer and performer in the eight solo interpretations of open scores, each from different composers, on In/Completion.

What’s particularly enriching about this release is the context Barbiero provides. While the liners provide personal notes for the whole project and each score and interpretation, his contributions to the IM-OS journal provide a more in-depth treatment of Cristiano Bocci’s Paths, Silvia Corda’s Traces, and Bruce Friedman’s O.P.T.I.O.N. system, including pictures. For comparison, most of the selections have other interpretations floating around, such as these recordings of Makoto Namura’s Root Music, Alexis Porfiriadis’ Spotting Nowhere, Cristiano Bocci’s Paths (with the composer and Barbiero in duo), Bruce Friedman’s O.P.T.I.O.N.S., Wilhelm Matthies GC 1, and (of the many) Morton Feldman’s Projection 1. Listeners are often in the dark on composition and performance interpretation practices; In/Completion, refreshingly, illuminates it.

The eight tracks total 40 minutes, with only “Paths” lasting longer than 10 and most shorter than 5, creating a quick pace and more effectively juxtaposing the characters of each piece. While the range of technique and timbre - from the preparations on “OPTIONS No. 3” to the vocal hiss on “Traces” to tapping the strings with the bow on “5 Points 4 Directions” and all the various sonorous arco techniques - isn’t uncommon for solo contrabass records, and while there’s a nebulous homogeneity in approach signaling a singular performer, the sometimes drastic shifts in structure between tracks indicate the diversity of composers and compositions interpreted. While the primary roots of “Root Music” are often interpreted as notes on a staff, it doesn’t seem to do the spirit of material justice. I can imagine the hard plucks and hiss of “Traces” signaling a pizzicato path across the vertices on the page to the next Feldman segment. The variations of a theme on the choose-your-own-adventure of “Paths.” And the hard-edged collage of “OPTIONS No. 3” clearly reflects the randomizable hodgepodge of material from Friedman’s system. Receiving a little more information around the music, the listener can further engage not just in the music itself but in the imagined possibilities of the music.

Jeremiah Cymerman / Charlie Looker - A Horizon Made of Canvas (Astral Spirits, 2021)

Jeremiah Cymerman and Charlie Looker forge atmospheres of desolation and sustained tension on the duo for clarinet, pedals, piano, and guitar, A Horizon Made of Canvas.

While the briefer “I’ll Show You What You Are” and “Samson” are more forward in volume, density, and aggression of attack, A Horizon Made of Canvas is generally hushed, austere, languorous. Clarinet more often slinks in and out of sounding, quavering, souring raspberries’ usual humor into desperate gasps. Each sound hangs in the air with the dispirited, sparsely-played piano and guitar, alternated among tracks, together eliminating the silence with a menacing environment of eerie and howling reverberations, creaking, disintegrating tape whirr, buzzing flies, low-end quaking, obscured voices, and singing cymbals. But they don’t necessarily play together; they are dissociative, obliquely communicating through volume and density. There is no climax, no catharsis, and any bursts of wrath are quickly inhumed by the oppressive ambiance.

EKG - 200 Years of Electricals (self-released, 2021)

Ernst Karel and Kyle Bruckmann craft “glitched” electric soundscapes with acoustic elements on 200 Years of Electricals.

This long-standing duo, with a history stretching towards the beginning each musician’s recorded work in the ‘90s, returns 20 years after their first recording, Shift or Latch, and after a decade-plus recording hiatus. Thus the duo documents a decade of individual development reunited, facets of which were represented in 2020 by Karel’s contributions to “Division Streets” from Unity Gain’s Superposition and “Cassette Field Recordings, Thailand 1993” to Building A Better Reality: A Benefit Compilation and by Bruckmann’s Triptych (Tautological), Draußen Ist Feindlich, and Brittle Feebling, the latter with Tom Djll, Jacob Felix Heule, and Kanoko Nishi-Smith. For previous listeners of EKG, what’s particularly noticeable here is the absence of trumpet from Karel, who focuses on analog electronics and microphones; Bruckmann plays oboe, English horn, analog electronics, and electric organ. Their blended approach to false dualisms in music - electric/acoustic, improvised/composed, etc. - continues.

Across two tracks and half an hour, the episodes of “St. Paul suburb” make half the material here. In them, the static silence of field recording and mic’d wind meet with sounds from flying creatures like chirping bird and buzzing fly, in turn met with man-made air manipulations from a leaf blower, traffic swooshing by, an overhead airplane, and a back-up beeper. In turn, these natural and found sounds mingle and blend with electric layers, chirps and horns with bleeps, bloops, clicks, and cuts, fly and leaf blower with electronic hums and drones. Though not necessarily present all at once, the similar characteristics in sonic attack and ranges of some of these sounds seem to draw comparison, perhaps making the listener think about how or why we separate the natural and anthropogenic spheres, or the musical and “non-musical,” among other boundaries. While these are salient points in listening, the majority of time is in electric layers. If there are acoustic instrumental inputs on the “St. Paul suburb” episodes, I don’t hear them yet. Layers of different pulse, frequency, and timbre enter and exit, overlaying to create subtle polyrhythms, and a frequent tactic seems to be temporarily increasing the volume of a layer to obscure more significant adjustments in another, causing some wonderment in how much the sound environment has changed when the volume of that layer decreases again. I doubt EKG shares many, if any, aesthetics or techniques with glitch music, but its collage, punctuated by sometimes-beat-forming crackling, pops, and clicks, doesn’t feel far off from it.

Indeed, there’s a practically danceable beat towards the beginning of “Periodicities mit Wurlitzer,” which also has an lumbering low-end rumble reminding me of some dub techno. The track somewhat evenly divides the other half of material with the other more obviously acoustic-featured track, “Rondo.” The former uses a variety of pulses from organ whirr to create a polyrhythm with electric layers; the latter uses wind instruments, air notes, whistle-lisps, raspberries, and key clicks, to communicate with a somewhat mimicked and mimicking electric environment, not dissimilar to the treatment of recorded sounds in the “St. Paul suburb” episodes. I’m unsure if the acoustic instruments are ever electroacoustically manipulated, but they are certainly well-blended.

Zachary Good and Ben Roidl-Ward - arb (Carrier Records, 2021)

Clarinetist Zachary Good and bassoonist Ben Roidl-Ward make melodious multiphonic studies for harmonic interaction on arb.

At six tracks across half an hour, each piece is an efficient sketch, rarely changing structure within tracks but using another to explore variations. The three-note tune with each sounding separated by silence on “Fairchild” and a similar tune played continuously on the title track; the unsynced long-duration tones of “2pm Front Room” and the staggered tone progressions of “Prid;” the gurgling bassoon and morse pulse of clarinet on “Guby” and vibratory train horn and glimmering overtones of “Rege.” More than one line from each instrument is nearly always audible, but the ear is drawn to harmonic beatings, parsing out the cause of fluctuations in pulse from the primary soundings. Despite a seemingly methodical approach, the sound is not sterile but instead feels full of heart and soul, from the tunefulness of the music but also the relatively quick clip of soundings compared to the long-duration, droning structures most often used to tease out beatings. Not to mention the intimacy of recording, in which breath, key movement, and auxiliary rattling is heard as clearly as tones. Especial appreciation must be given to the title track, in which the melody breaks down to a whooping bird call, a cathartic gradient, air notes releasing as if from scuba gear or an iron lung, unveiling a fragile overtone melody, with a tender lyricism rare for this kind of music.

George Lewis - The Recombinant Trilogy (New Focus Recordings, 2021)

The Recombinant Trilogy gathers three performances of electroacoustic George Lewis compositions for flute, cello, and bassoon that blur the boundaries of sound production and sound reproduction with a concern for space.

The three compositions are part of a series of recombinant music, presumably named for using pieces of the acoustic input for creating electronic output of varying originality, that began in 2014 with Emergent and has most recently produced Memory/Mutation for two violins (specifically String Noise) in 2019, the latter of which is not present here. The name makes me wonder if this is in communication with David Cope’s methods. Also interesting is that these compositions don’t utilize the signature Voyager software but other programming from Damon Holzborn, who I believe has since co-developed Voyager. Claire Chase, the flautist for which Emergent is composed for and performed by, commissioned the piece as part of her larger Density 2036 project for solo flute works and another recording can be heard on part ii, both with Levy Lorenzo on electronics. This recording of the 2014/2015 composition Not Alone appears to have been previously released on cellist Seth Parker Woods’ own asinglewordisnotenough, where he also covers electronics. And this is the first recording of the 2017 work Seismographic, commissioned and performed by bassoonist Dana Jessen, who is joined by Eli Stine on electronics here.

“Emergent” has three clear voices, which seem to be the acoustic, the electroacoustically manipulated, and the electronically generated. There’s a certain confidence that the ear can discern each, but this falls apart quickly when it realizes the flute might be copying the electronics, not the other way around, and it’s possible either could be manipulated for the third voice. Increased tempos and repetitive soundings can confuse the ear by closing the gap between similar-enough timbres to make voices practically indistinguishable but slower tempos, despite the increased time to interpret timbre and origin, can also confuse by shifting the order of voices. The chorus is birdlike in its flurry of notes, flighty, with key clicks and air notes. Likewise the array of bowing techniques on “Not Alone” is impressionistic, but only two clear lines - acoustic input, electronic output - usually distinct in timbre, though the delay, the material used for the output, and the order of who’s responding to who seems to vary. “Seismographic” uses fragmented quadraphonics to create a maelstrom of mimicked extended techniques. Beyond flip-flopping electric and acoustic copying, each piece uses timbre, volume, and delay to create the effect of spatiality or dimensionality by “throwing” sounds, but “Seismographic” does so most overtly with its several channels. Though not heard here, I have a hunch that Lewis composed Memory/Mutation for String Noise, after seeing them perform their Alvin Lucier repertoire (see the Quatuor Bozzini review in this issue), because of their comfort with compositions illuminating the spatiality or dimensionality of music. This kind of ambisonic translation is what really sets this music apart from other electroacoustic music that addresses origin, copy, liminality, and identity.

LOTE - Radu Malfatti: hensou (2017) (self-released, 2021)

The ensemble LOTE blur instrumental and environmental, acousmatic and known, and sound and silence on their performance of Radu Malfatti’s spacious, ambiguous, porous composition, hensou.

LOTE is directed by Cristián Alvear and, like the director, is resolutely dedicated to the performance of new experimental compositions. This release comes from Alvear’s frequent offerings on bandcamp, which also include Michael Pisaro-Liu: E là Fora with Cyril Bondi and Auralidad with Léo Dupleix from just this year. Though comparatively dormant, LOTE also has a bandcamp offering performances of compositions from Jürg Frey, Mark So, and the ensemble’s own Santiago Astaburuaga. A translation of the title might mean disguise or masquerade, perhaps reinforcing an interpretation that the composition blurs sources and perceptions of sound.

As is probably expected from the composer and ensemble, the volume is quiet and the space between more audible soundings is generous on this hour-long performance. There are markedly recurring sounds - a harmonic swell, a string of 1-note guitar, a high-frequency pitch, scraping or rubbing - but, even after dutifully trying to track a structure, their durations, the intervals between recurrences, and the order in which they occur appear irregular. Even more so as they appear to give way to crackling plastic, breath, bells, and a single piano note as the performance progresses. Auditorium sounds - whispers, shuffling, chairs creaking, photo snaps, the room itself - and faint sounds outside of the auditorium, like traffic, back-up beepers, and sirens, might be heard throughout. While these sounds and their sources are (probably) identifiable, there are several that are not. What’s more is that the perception of sounds and their sources is increasingly blurred. Was that really a back-up beeper or siren from outside, or a low-volume sine wave from the performers? Did the shuffling come unintentionally from the audience or intentionally from the performers? The scraping or rubbing appears to change instruments or materials, but never obviously, and might blend with breath or roomsound. The harmonic swells likewise appear to change sources between organs, strings, electronics, and others. While the ear, revealing a listening bias, is certainly drawn to what is perceived as intentional sounds from the performers, hensou effectively confuses the boundaries of instrument and object, intention and accident, performer, audience, and environment, and even sound and silence. By the end I might have felt silly for trying to impose a music on it, which it is.

LOTE on this recording is: Cristián Alvear; Santiago Astaburuaga; Felipe Araya; Nicolás Carrasco; Christian Delon; Sebastián Jatz; Marcelo Maira; Francisco Martínez; Álvaro Ortega; and Álvaro Pacheco.

Roy Montgomery - Island of Lost Souls (Grapefruit, 2021)

Guitarist Roy Montgomery’s singular style of lo-fi, psychedelic, post-punk instrumentals continues on Island of Lost Souls.

Celebrating Montgomery’s 40th anniversary as a recorded musician, which began with the first recordings from the short-lived Pin Group during their only full year of activity in 1981, is a four-album set with a metered release through 2021, of which Island of Lost Souls is the first album. While similar in scale to the triumphant “return” of RMHQ, the better digestibility of dosed LP-length albums will probably make a more positively-received listening experience by offering a choice to consider the four releases wholly and/or individually. At just four tracks with a sidelong closer, Island of Lost Souls explores alternate states not just through psychedelic sounds but longform repetition too while also spotlighting plain influences on the music, particularly from film and other music.

“Cowboy Mouth,” named after the play by Sam Shepard (to which the song is dedicated), is an airily picked dreamelody with ringing reverb filling in the spaces, anchored by a springy low end beat, with a melancholy harmony extruded from the effects; true to the dedication, the feeling is cinematic, especially western, with a mood like what Days of Heaven or Paris, Texas might evoke. With bright, slowmotion surf lines gliding over a dark echoing throb for a beat, the darkmotif dancehall of “Soundcheck” recalls Bernard Sumner and his innumerable acolytes but also the colorful repetitions and variations on a theme of a raga. “Unhalfmuted” focuses on chords rather than the picked lines of the previous two tracks, with layers of sub-bass rumblings, soaring vocal-like chorus, and carnivalesque organ-effect explorations. The sidelong centerpiece, “The Electric Children of Hildegard von Bingen,” hails Florian Fricke, explicitly recalling the ecstatic music of Popol Vuh and to which the transcendent Coeur de verre seems an especially apt comparison. Underlain by the vocal-like chorus, it is an ascending spiral curve of looped and delayed chord variations, a more devout companion to “Sister Ray.” When Montgomery arranges a sidelong track, it is always a gift. Montgomery’s style is the same as it ever was but, like these tracks, in shifting similitudes. There is a certain peace in his steady strum gently refracting in a pool of reverb.

Anthony Pateras - Pseudacusis (Bocian, 2021)

Anthony Pateras’ composition for taped septet and live septet, Pseudacusis, is a tricksterish and mysterious chamber soundscape.

The title could be translated as “false hearing” and the scant notes about the piece only mention it is “audio hallucinations,” so the mind is immediately attentive to possible sonic illusions while of course limited to gathering information from the potentially unreliable ear. The 50-minute recording is divided in to seven tracks, a number that may contain some meaning considering the septets, that don’t flow, except perhaps II>III and V>VI, yet feel continuous beyond the general instrumental approach through several recurring motifs and markers - rolling crashing piano clusters, steplike measured piano notes, a gong or chime. The chime or gong seems to mark abrupt changes in dynamics and density, though these also occur without it, and the mind questions whether track transitions are just similar changes. The abrupt changes add a tape splice effect to both septets, whether or not it’s actually there. Rearranging sequencing for flow doesn’t seem to produce added continuity. The ear is most drawn to piano, percussion, and electronics since they are the most discrete sounds in a bed of often long-duration sustained soundings and swellings. While I question whether I could always discern the contrabass from cello from violin or the clarinets from saxophones, and while instruments blur - the wheeze and squeal of wind with string noise, the electric aviary with the small sounds of objects and drums - the sounds don’t seem acousmatic either. At least, the instrumental source seems apparent, if not whether they are coming from tape or live performance. The truth of light harmonic beatings on III and VII are certainly questioned as difference tones or some similar psychoacoustic mirage. But with all the possible ways the ear could be tricked, it wouldn’t know it without context, which is itself a kind of trick. Still, concept aside, the piece is dense though uncrowded for all its instrumentalists, complexly-layered yet leaning quieter and slower, timbrally-rich, and the changes in density and dynamics lend an engaging movement.

On this recording, the live septet is: Lucio Capece (bass clarinet/soprano saxophone); Krzysztof Guńka (saxophones); Riccardo La Foresta (percussion); Mike Majkowski (contrabass); Anthony Pateras (piano); Deborah Walker (cello); and Lizzy Welsh (violin). The taped septet is: Aviva Endean (clarinets); Judith Hamann (cello); Jonathan Heilbron (contrabass); Scott McConnachie (saxophones); Maria Moles (percussion); Anthony Pateras (electronics); and Erkki Veltheim (violin).

Quatuor Bozzini - Alvin Lucier: Navigations (Collection QB, 2021)

The string quartet Quatuor Bozzini perform five Alvin Lucier compositions that share a hyperfocus on the behavior of waves in the performance space on Navigations.

Though most of these compositions have been in Quatuor Bozzini’s repertoire for over a decade, I believe this is their first recording of Alvin Lucier. For comparative listening beyond brief clips of past performances on the quartet’s own website, there’s at least Tapper from String Noise released just last year, Unamuno from EXAUDI, and Navigations from Arditti Quartet and Noël Akchoté. The track sequencing here feels balanced, with the longer beating pieces on either end and the vocal track in the center, separated by tapping pieces.

“Disappearances” is a sixteen-minute track of clean, sustained soundings with harmonic beatings (or illusion of them) rising from them. Upon reaching a resonance with their instruments, each other, and/or the room, the overtone pulse alternately quickens and slows - buzzing, humming, singing - occasionally, true to the title, disappearing, I imagine from some canceling synthesis trick or perhaps a interruptive shifting harmonic configuration similar to the other pieces. The similarly durative, sustained, and beating “Navigations” seems multiphonically-played with a faint fluting accenting the disappearances. The ear might hear the rotating matrix of four tones and miniscule differences in pitch, decreasing volume, and decreasing tempo through the track, intended to draw attention to the room. The relatively brief “Unamuno” is another rearranging pattern of four tones with attention to performer placement in space; usually performed with voice, here it is mixed string and voice. “Tapper” uses the butt of the bow against the body of the instrument to collect information about the room as the performer walks the space, utilizing different tempos, forces, and parts of the body. In making it a group performance, the ear feels distracted from the character of the room itself towards the relative space of the performers and their overt polyrhythm, which is an interesting shift in perception. Representing the performance space in such a way, through multiple facets, requires a tenuous synergy from composers, performers, and recording and sound engineers; this recording achieves that inclusivity of the fifth instrument of the quartet.

Quatuor Bozzini on this recording is: Isabelle Bozzini (cello); Stéphanie Bozzini (viola); Alissa Cheung (violin); and Clemens Merkel (violin).

Mariel Roberts - Armament (self-released, 2021)

Mariel Roberts makes hostile electroacoustic environments for solo cello and pedals on the four unedited improvisations of Armament.

Roberts is a force of nature in new music. Just last year, she appeared on at least Ian Power’s Diligence, Charlie Looker’s Pleasures of a Normal Man, and David Lang’s the loser, stylistically disparate yet all delightful. Just last month, she appeared on Christopher Bailey’s Rain Infinity. In April, she will appear on Nate Wooley’s Mutual Aid Music, with fellow ex-MIVOS Quartet bandmate Josh Modney. While the earlier solo records, Nonextraneous Sounds from 2012 and Cartography from 2017, interpreted a repertoire leaning at turns tense, dark, and noisy, Cara from 2019 coalesced those aesthetics into her own compositions. The set-length Armament adds electronics for a jarring electroacoustic dialogue between the familiar and alien and the warm and harsh or, at times, the harsh and harsher.

The electroacoustic output is nearly always present alongside the acoustic input, mimicking Roberts’ attack on the strings, distorting its character yet assimilating its beat, mutating the beat with delay into various martial thrums, subsuming it all into an organic wall of noise. Roberts readily changes the delay tempo and volume for impactful shifts in momentum, sometimes rhythmically dropping it out completely to create an effect like a flickering light snapshotting an approaching monster in pitch black. It’s a two-way street though, and Roberts occasionally mimics the living wall, matching its insect chitterings with skittering bow on the strings and body in “Lock” or electric crackling with frictive vibrato in “Interlude.” Beyond being actively adjusted by Roberts, what makes the electric environment so dynamic is the rich range of acoustic techniques, from classical jaunts, polyphonic bowing, and descending glissandos to screeching hair, muted plucking and palming, and sawing. It’s a moody relationship with powerful emotive capability, embodied in the last moments when gasping static scuba respirations give way to melancholy solo acoustic cello. Commenting on the title, Roberts writes, “everything feels weaponized right now - things that should not be;” in its confrontational feedback between instrument and noise, Armament might provoke listeners to think about their own input and its effects on the output of their communities and environments.

Ingrid Schmoliner / Adam Pultz Melbye / Emilio Gordoa - GRIFF (Inexhaustible Editions, 2020)

Pianist Ingrid Schmoliner, contrabassist Adam Pultze Melbye, and percussionist Emilio Gordoa play small-variance structures to explore the many facets and complex relationships of repetitive soundings on GRIFF.

This is Schmoliner’s first recording with Melbye or Gordoa, and perhaps the first since her wondrous collaborations with hornist Elena Kakaliagou on Nabelóse and Paraphon in 2017 and 2018. Melbye and Gordoa have previously recorded together, on Berlin Split with Josten Myburgh and Hyvinkää as part of the M0VE 5tet. Schmoliner plays with a percussive yet unaggressive attack here and Gordoa mostly plays vibraphone, allowing this rhythmic unit to not just phase phrases but instrumental identities too, as the vibraphone sometimes assumes the more tonal movement of the piano and the piano sometimes assumes more metronomic pulsings of the percussion.

“But Still” begins with a little over two minutes of a repeated plucked contrabass phrase, soundings separated with plenty of space. Then the piano, with single notes, moving around the keyboard. And then, a little over two minutes later, the vibraphone, with singles notes, moving among the bars. The staggered entrance recalls setting up a canon, which I’m not sure this is, but the pace of rounds would be so slow as to lapse a listener’s memory of what the repeated phrase is and how it might have changed. The ear is instead at first drawn to the decay of sounds that occupy the space between soundings, which enter in order of increasing duration. While all three instruments quickly establish a cluster of simultaneous sounding, they just as quickly dismantle it. The contrabass seems quite literally the baseline, remaining relatively static, while the piano and vibraphone drift at different tempos. As they recluster towards the end, all instruments have played different pitches and chords. It seems like a slow phasing piece that encourages a close listen to the changing relationships of decay as sounds rearrange themselves in space. “From Real” feels similar, but faster and looser, with roles changed, and extended technique a little more characteristic of the echtzeitmusik scene, though never acousmatic, like fluttering and rubbed bass, inside-muted piano, and objects on the vibraphone sounding like a zimbelstern. The dizzying piano variations of “Bell Skin” recall what makes Steve Reich or Chris Abrahams so exhilarating, and the contrabass and percussion appear less structural and more textural, the latter generating a guttural roar somewhere between a screeching cymbal and blown drumhead and also relieving the piano for a time with its own mallet variations and phasings. As “From Real” felt like a version of “But Still,” so “Moss Rock” feels like a variation of “Bell Skin,” faster and looser and more textural. That these tracks seem like variations of each other is an interesting scaling of the structural concepts seemingly at play within tracks.

USA/Mexico - Del Rio (12XU/Riot Season, 2021)

USA/Mexico embraces extreme noise on the sludged-out doomed grooves of Del Rio.

Guitarist/vocalist Craig Clouse, drummer King Coffey, and bassist Nate Cross are joined by a new vocalist in Colby Brinkman. The recipe here isn’t poles apart from Laredo or Matamoros, but is a more significant developmental leap than between those first two records. Distortion, fuzz, overdrive, boost, volume, sub bass all (somehow) seem maximized. The volatility lends a fragility to an otherwise aggressive music, always edging on amplifier blowout, if they’re not already burning when the tape started rolling. Likely as a result, the pace is slowed to tempos on the low end of funeral and drone doom and, whereas most previous tracks hovered around the five-minute mark, two of three tracks here stretch to the mid-teens. Comparisons to extreme metal genres are further encouraged by the vocal delivery, now sparse and unintelligible growls and grunts. While there are some breakdowns, wailing feedback solos, and small variations in structure and effects, the groove lumbers forward, largely unchanged in each track. A sonic juggernaut with, for all its effects-laden frankensteinian electricity, an organic character in the autonomous crash and clip of its sine and step waves and their chirruping blizzard static.

Thank you so much for reading harmonic series. If you appreciate the music and the words about it in this newsletter, consider sharing it as a method to advocate for the music and the people that make it possible. harmonic series will always be free and accessible without a sign-up or sign-in but, if you appreciate the efforts of the newsletter specifically, consider donating; donations offset the cost of the newsletter, determine stability and growth, and, in the event it becomes a collaborative effort, will be used to provide contributors a respectable fee. As always, readers are encouraged to reach out about anything at all, even just chatting about music, to harmonicseries21@gmail.com.