1/17

conversation with John McCowen; notation from Hannes Lingens; reviews

$5 Suggested Donation | If you appreciate this newsletter and have the means, please consider donating to it. Your contributions support not only the regular writers but the musicians and other contributors that make it possible. For all monthly income received, harmonic series retains 20% for operating costs, equally distributes 40% to the regular writers, and distributes 40% to musicians and other contributors (of this, 40% to interviewee or guest essayist, 30% to rotating feature contributor, and 30% equally to those that apprised the newsletter of work it reviewed). For the nitty gritty of this system, please read the editorial here. The newsletter was able to offer musicians and other contributors $2.27 to $6.06 for April and $2.15 to $11.49 for May. Disclaimer: harmonic series LLC is not a non-profit organization, as such donations are not tax-deductible.

conversations

John McCowen is a composer, performer, improviser based in Reykjavík and perhaps most associated with the clarinet family. Over video chat we talk about cars, rivers, Reykjavík, the sound in your head, bass, silence, teachers and teaching, shitty flutes and recorders, and recording and records.

Recent releases include Bitter Desert with Jeremiah Cymerman and the solo Robeson Formants. A video of a recent duo with Roscoe Mitchell is available here.

JM: Keith, can you hear me?

KP: Yeah. Can you hear me?

JM: Yeah, yeah.

KP: Perfect. How’s it going today?

JM: Good. So where are you at?

KP: Uh, in Austin, yeah. So I think we share a little Carbondale history but I’m certainly not from Carbondale. I’m from San Antonio. And then after my two year sentence in Carbondale I decided to move back to central Texas.

JM: [laughs] I remember, I think you said you were studying geology in Carbondale?

KP: I was, but that went down south. I went to Carbondale for a master’s in the geology of rivers but I kind of went… it was just offered to me after being rejected at the places I actually wanted to go. So instead of studying the types of rivers that I wanted to, I was studying bigger rivers like the Mississippi. And without really realizing it, I got into this game of being a cog in an ideological battle against the US Army Corps of Engineers’ flood policies, which I can support but I didn’t really want to be a part of. You probably caught this too but the people at the university were also very partnered up, so going from an undergrad environment where everyone does everything together to a graduate environment where everyone goes home to their families in a new town was also kind of tough.

JM: Yeah, but then I guess maybe you get the kind of situations where sometimes people don’t want to go home to their families so then you end up at like Hangar 9 or something like that [laughs] The rivers thing is interesting because my dad grew up in Cairo.

KP: Oh, yeah, the first time I saw Cairo I was like, what is going on, ‘cause it’s literally an iron curtain around the city.

JM: Yeah, yeah, so my dad’s dad operated a crane on the Ohio River. And the first time - I think I was eight - my dad took me down to see the house that he grew up in, it’s just burnt in my memory. It’s like what you think when an older generation takes you to see their home. Like some little one bedroom house and I’m like, wait you had four brothers and sisters and an uncle that lived with you, and he’s like, well you know we just slept wherever [laughs] But then you look in the back yard and there’s just a giant hill, and at the top of that hill, I saw a tugboat going by. And I was like, wait what’s going on, what is this. And he was like, oh well the river’s high. So their back yard was the levee wall and just to be able to sleep in that house knowing that the river is thirty feet above you, it’s crazy.

KP: Yeah, I guess a lot of what I was dealing with… you know the New Madrid spillway? It’s kind of more in Missouri…

JM: mmhmm

KP: So whenever the river gets high, that’s a designated flood zone. They open that up and it’s pretty much Missoula in that little spot. And farmers love that spot because it’s great fertile land, but you can’t live there. So I was dealing with trying to model that, get people to realize like, yo your life is literally ruined by living here. And something like that has to exist because the way the Mississippi is treated in that area is… I guess it’s a little disrespectful. Like living fifteen feet under the water.

JM: Did you ever go west of Carbondale to areas like Grand Tower, LaRue-Pine Hills, those areas?

KP: No.

JM: Grand Tower is this tiny town on the Mississippi River that has gas lines going across the river, so they look like these tiny bridges, suspension bridges, but they’re just gas pipelines. And it’s one of these towns that just gets flooded, all around it, every year, and the town is just used to it, you know, it’s a town of like five hundred. And then LaRue-Pine Hills is right above it, and… you ever heard of Inspiration Point? It’s like the high point in southern Illinois and in the Fall and Spring - I might have my times wrong - but they close off the roads for this giant snake migration. You can’t drive through this area because the roads are absolutely covered in copperheads, rattlesnakes…

KP: [laughs] what?! Just fleeing the river, the flood?

JM: Yeah, I’m not exactly sure. It was this terrifying thing as a kid and we would go out there and just see it, the road literally covered in snakes.

KP: Oh my god that’s terrifying. Well, how’s Reykjavík treating you? [laughs]

JM: [laughs] Reykjavík is good. I’m at my studio space out here which is really nice. I mean it’s just a whole different world out here. Compared to living in the US, everything is just at a totally different pace.

KP: Yeah, a lot slower and chiller…

JM: Yeah. And it can be aggravating, as an American. Because people aren’t very direct here. Like people will drop subtle cues about what they’re trying to convey to you and expect you to pick up on these cues instead of telling you, this is what I want you to do. And Americans, we just want directness. Like say, hey get out of my way, instead of just slowly pushing into me for like fifteen seconds [laughs] Or just say, excuse me. But yeah, it’s great. I’m teaching here, teaching improvisation at the Iceland University of the Arts. And another course that I designed in the Fall. In that respect, if I was still living in New York City, I wouldn’t be teaching at a university.

KP: Yeah, I just recently got around to your interview with Jeremiah Cymerman from like 2017 and in that you actually mention that you and Bergrún [Snæbjörnsdóttir] are already thinking of moving to Reykjavík.

Listen to John’s conversation with Jeremiah Cymerman here

JM: It’s kind of been something… well, she’s from here. So it’s something that had always been talked about and I think it was about four months into COVID the conversation kind of took on a certain seriousness. I mean everybody had lost their jobs, I was getting unemployment checks, and all that kind of stuff but, talking with coworkers of mine back in New York, the future didn’t look very good for where I was working. Also, on top of that, in New York I was working building stained glass windows as one of my jobs and the other job I was teaching at a school, like a very expensive school in Brooklyn. And before the pandemic at my job at the school I was making $25/hour. And I mainly worked in the after school program. I’d go to the stained glass shop and then I’d go to the school and work from like 2:30 to 6:00. So when they decided to bring the school back, like months into COVID, I get an email being like, well you know we’d like you to come back to work, and all of the sudden my pay dropped $10. Like this is a school that has a $100K tuition for kindergarten. And they’re taking some of their lowest level workers and going like, hey we need you on the frontlines of the pandemic with these kids will you take the same wage as McDonald’s down the street. And so yeah that was kind of like, I think this is the direction we’re going in, maybe I need to try something new.

KP: Yeah. Yeah, yeah, labor’s not a pretty picture here. So that was in the middle of your ISSUE residency too, were you a little tied down with that? Like did you have to wrap that up before you were able to move?

JM: Uh, I mean ISSUE was pretty quick to move everything online. And they were very open for dealing with the situation however we could. I mean, I recorded the little EP I released, Two Energy Cops at 3AM, I recorded that in the ISSUE space like 20 days into the COVID lockdown. ‘Cause the ISSUE space was just empty and nobody was in or out but, looking back at twenty days into the pandemic, I was entering that space and I had a box of latex gloves, not touching anything [laughs] I have a respirator I use for soldering and I’m going in there and making… I mean no one else was using it but I wanted to make sure I wasn’t screwing things up for anybody.

KP: Nice. And have you found a good group to play with in Reykjavík? I imagine you work some with Bergrún but other players?

JM: Um, mainly there’s… Iceland has a lot of really great artists. I mean, their government’s fucked up, too. Their government kind of looks to America for the model for how they want to operate in late capitalism. It’s a little shaky but also, you know, the far right side of their government is more like our center left. Visual artists, designers, sculptors, that’s what’s been nice about here. I look at who I interact with and it’s not just musicians, it’s people from all different kinds of fields of art, which is really nice. And also makes for conversations that kind of have this endless blooming to them. ‘Cause if I’m talking about music, the viewpoints I get from people from different fields are nothing like I would get from just talking to musicians. But when it comes to improvisers, teaching the improvisation course I teach has been really interesting. I’ve been teaching it for two years now, so just seeing how these students change. Because in the course everybody plays every day the class meets. And so just seeing these people develop their own language has been really exciting. And I don’t play in class, mainly because I don’t want to influence the students. Like I want them to really deal with what their own personal language is. And I don’t want someone who just might not know what’s going on to be like, oh I guess this is just how I’m supposed to improvise.

KP: And, I guess… in your conversation with Sean Meehan in Sound American you kind of mention… and I mean it’s mostly Sean, but there’s a couple points where you talk about your thoughts too and one of them is kind of finding your voice through rejection as much as acceptance. In that context you’re talking about Ayler mimickry as the example but in what other ways or in what overarching ways is rejection still shaping your voice?

Read John’s conversation with Sean Meehan here

JM: Well, I just try to… I tell my students this, that the only thing you have is what you hear in your head. What you hear in your head is the purest thing you have. So to hear somebody else do something and go, that’s what I want to do, that’s not your voice. That’s just you connecting with something and taking that. And I think it’s much more productive to, say, go to a concert and though you may appreciate it, you may enjoy it, you may hear things going on and go, oh that’s something I don’t want to do. It’s very important to know what you don’t want to do. I think it’s more important than knowing what you do want to do, because you’re getting closer to your own voice. Like I said if you hear people doing something and you like it there’s a higher chance that you just copy what you heard as opposed to sitting with that sound and trying to hear it in your own mind. And I’m kind of concerned, as things speed up in this day and age, I feel like engagement with music is much faster. I’m afraid that people don’t sit with music long enough, that they just take it on an aesthetic level and run with it. Music, it’s just important. I mean, I don’t know if that answered your question.

KP: No, that’s perfect.

JM: For example, when I was a clarinet student as SIU, I started out transcribing Benny Goodman solos, because that’s what a good clarinet player does, you want to figure out what he’s doing. And very quickly I realized that it would be better for me to actually transcribe Lionel Hampton’s vibraphone solos and adapt those to the clarinet as opposed to transcribing Benny Goodman and just sounding like every other clarinet player that’s already existed. You know, that’s no good for anybody. Where’s your own voice. You need to look outside of your own instrument. Like if I was a clarinet player only listening to other clarinet players I would just sound like other clarinet players, and that’s no good for anybody.

KP: [laughs] Yeah. It kind of reminds me of what the guitarist, Cristián Alvear… I might be misrepresenting his thoughts a bit here, but whenever we’re talking about interpreting notation he always mentions not just to see what’s on the page as a call to action but interpret it as a limit of what you can’t do. I guess in other words by defining what something isn’t not from what it is but from how it’s incompatible with what is you’re opening up the field of what you see as possibilities.

JM: Oh yeah, absolutely. I think it makes it more streamlined for the brain to know what can’t be done.

KP: Yeah. I guess kind of going back to the sculpture bit, I imagine talking to some sculpture artists is funner for you based on your ideas of dimensionality in your music?

JM: I don’t know… not really.

KP: They’re not that out there?

JM: When it comes to that kind of thing… there’s this thing about being an artist in Iceland where you know there is this whole world of music here which is like straight-to-Spotify chill-music-to-listen-to type of stuff that gets churned out. And it’s frustrating for me to see geography and nature represented under such a narrow lens. To see a majority of music coming out of this country that is influenced by nature - and maybe this is a bit fucked up for me to say as an American living here, not being from here - is that most art in the field of music from Iceland being represented under this guise as like the harmonic language of the 18th and 19th century is crazy for me because when the volcano is going off who’s making like Ana Maria Avram type stuff. But all that said, the music scene in Reykjavik is really booming. A lot of honest experimentation happening and cross pollination between worlds. We have Dark Music Days, Raflost Festival, Mengi, Post-Husíð, etc. Post Dreifing is a young collective of artists under the mindset of “do it together.” These young artists are incredible. They’ve inhaled everything from Stockhausen and Björk to hyper pop and trap. It’s really exciting here. And we have amazing contemporary composers like Bergrún Snæbjornsdottir, Thrainn Hjalmarsson, Ulfur Hansson, Bara Gisladottir, and a whole lot more. I mean there’s a lot of people doing amazing stuff here, but also there’s a lot of mediocre shit [laughs]

KP: [laughs] Yeah, going back to finding people to play with, you mentioned a kind of relative isolation to Roscoe [Mitchell] in your conversation at Borealis, and that because of that you’re diving into your work. What are some of the directions that you’re diving into?

JM: Well it’s just been this long process of trying to get what I hear in my head out of my instrument. And usually the sound that I hear is very undefined. Like to pick up the contrabass clarinet and find some sound that I can tell is something I’ve heard in my head and then to sit with it, to just sit with it for an extended period of time, and just watch it kind of show me how it wants to be developed. And you know the longer you sit with it, the sound, the more it will tell you. And you kind of develop that form. And that’s something Roscoe and I have talked about a lot. He’s into this thing of, you know, you have one thing and then all of a sudden you have two, just this constant development of material. But when it comes to my work here, the latest stuff I’ve been developing, I haven’t really sat down with it. It’s mainly in my head. You know a lot of the solo work I do is drone based, durational. And the new album… I have a new solo album coming out this Fall which is a full-length solo record which is extremely droney and I think it’s like me going off the deep end in that kind of thing because I recorded it in Brooklyn right before I moved to Iceland, so it was the music that I had been developing in New York. And now I’m just kind of taking what I’ve done and seeing how I can interrupt it. And that’s where I’m at with it, kind of trying to fuck myself up on purpose.

KP: [laughs] Yeah the piece you played with Roscoe was pretty melodic compared to what I guess I would otherwise characterize some of your stuff as.

JM: Yeah, well, I like to be able to do all kinds of things, you know. I practice a lot of Baroque music. I have like the first four minutes of Eric Dolphy’s God Bless the Child memorized, I love to play that. I just love to be able to develop whatever I can and working with Roscoe like that, he’s very similar. Me and him, when we would get together, it was like… like going to Borealis with him, I think it was the first time we ever improvised together. And we had played together for years but mainly it was like Handel, CPE Bach, old Art Ensemble [of Chicago] tunes rearranged for recorder, it was whatever music was on paper in his house that had more than one stave on it, we were playing it together and then breaking it down and talking about it. So going to Borealis with him, I mean we played together for six days before the concert, you know, 10AM to 5PM, and we developed the piece we played over the course of those days. And I probably learned more about music in that week than I have in the past decade.

KP: Nice. So I was listening to the talk in the car with a bad reception but I think I heard a bit where you were kind of amazed by his compositional approach. And I think it’s said that he improvises something, transcribes it, and then builds an arrangement from that transcription, which seems like the way that I hear about the most, so it got me interested in what your approaches are. Since you just mentioned that you like to sit with things as well. Is it like a - particularly working with a lot of harmonic interactions - is it a more calculated approach or more play and then coming back to something…

JM: Well when I’m working on a solo piece it usually starts from just me playing something and having a connection with it. And when I notice that connection I don’t have… when I have that connection I realize in that moment, OK this is gonna take a lot of time. And then every day after that connection point, I have to be there every day to see what comes next. It’s just playing playing playing playing until I get to a point - and I’m recording demos the whole time - until I get to a point where I think the form is finalized. And then what’s interesting is that when I get to that point where I think the form is finalized then I need to spend more time just practicing that form. And then I might start performing it in solo concerts. And the next thing I know, after I’ve performed it in front of people, the form has changed. So there is the form of the piece in isolation, then the form changed when I have taken it to an audience, and then the form will continue to change for as long as I play it. So it’s always changing. It can be extremely hard to figure out when to record something. Because I’ve recorded a lot of solo pieces of mine where I’ve gone, oh well I should’ve waited a couple of months because this cool thing happened at this show and I wanted to develop that.

KP: Yeah, and I’m assuming a bit of that is dependent on space too, right, not just what you’re doing on the instrument?

JM: Uh, certain resonant spaces will allow me to hear more high harmonics or so on so forth and then I can really kind of know where those harmonics are coming from in my throat and my oral cavity and then be able to work with those or freeze them in places so they interact with other tones… yeah. But for the most part the instrument is in my face [laughs] so I’m always hearing that sound first. Which kind of sucks sometimes because I know that I might be doing a concert and all the interactions I’m hearing right in my forehead the person in the back row is probably hearing like one high pitch. And it took me awhile to realize that. ‘Cause I was like, alright there’s all this stuff happening I hope this is interesting, and then I put a zoom recorder in the back of the room and it comes back like [test tone sound] and I’m like, ugh what the fuck.

KP: [laughs] Yeah, have you had some trouble recording… or I guess you mentioned that the form changes after you take it to an audience and after you record, so is that some of the feedback, that you do recognize that that’s happening and then you slightly adjust things to make it where something interesting is happening away from your face?

JM: Yeah I mean that’s been a lot of what it’s been. And recently I’ve started to consider… you know, I work with amplification these days where I have a microphone inside the instrument… ‘cause it’s been this long process of getting what I hear right against my face out into the audience. And to also allow the audience to hear the minute changes that are happening. And this microphone works really well for that. But lately I’ve been finding myself wanting to play concerts to like eight people seated inches away from me to just really get that… like I want people to hear what I’m hearing so this is the purest way to do that, to get as close to me as you can. But we’ll see. I might try doing some solo concerts in my studio space here or something.

KP: Yeah one of the caveats that I see on a lot of your recorded stuff is, hey this is not… there are no electronics here, this is acoustic phenomena. Is there a special concern with whatever microphone you’re using, filtering out… or filtering the acoustic phenomena in a way that doesn’t feel right?

JM: I mean, sounds checks are important. I need to make sure everything’s working correctly. But for the most part

the mic has been pretty honest. The main reason I put that kind of disclaimer on everything is the amount of people that come up to me and ask me, where’s the laptop, where’s the pedals, how are you doing that feedback, how are you controlling that feedback, and it’s like, nah it’s nothing.

KP: Yeah at first I interpreted it as a kind of aversion to electronics but then you got the sine wave study and the sine wave on Robeson Formants. I know you play with electronic players… Oh, so when you were having your conversation with Roscoe at Borealis, I had recently had a conversation with gabby fluke-mogul, who is also a Mills alum and they also happened to mention Roscoe’s recurring phrase “silence is perfect” which I kind of interpreted as, what you’re doing better be good because you’re messing up something that’s already good. But I wanted to ask how you think about the phrase and, larger, how you think about how your music interacts with silence.

JM: It’s mainly about not being lazy. Like I said earlier, all you have is what you’re hearing in your head so to you that’s the most honest thing, that’s the most perfect thing you can do. Because everything you've ever heard is being smashed together and allowing you to come up with something. And you have to be tapped into that because that’s as perfect as you can get. If you’re not thinking and you’re in an improv situation and you hear somebody playing something and you’re kind of not present and you just latch on to that person you’re pretty much a leech, you’re a parasite to the improvisational situation where you’re dragging that person down ‘cause you’re cornering them and cornering them and not allowing them to do what they want to do. And you’re not helping them in that situation, you’re literally sucking the life from their musical ideas. So that disclaimer of Roscoe’s is like, yeah silence is perfect so if you’re gonna break that silence you better come in with something just as perfect. And Roscoe’s whole thing is improvisation is composition in real time. He said something that really stuck with me when we were rehearsing in Norway, when we were rehearsing the composition we were developing. And at that point we had about ten minutes fixed. And we were getting ready to run it and I said, OK well we’ll run ten minutes and then we’ll just see what happens, and he looked at me and was just like, I’m not interested in not knowing what’s gonna happen I wanna know exactly. And it was in that moment that I was like, well we are gonna improvise, but.. yeah. So it is absolutely composition in real time. The way he thinks about composition in real time is extremely akin to like flute and recorder players, soloists of the Baroque era, where you might get… you’re never gonna play the same thing twice. You’re gonna ornament it this way, you’re gonna use this kind of articulation. It used to be a thing where you could tell a flute soloist simply by their articulation. And they were improvisers, they were master improvisers, and they could take a small amount of material and blow it up into this huge composition. You know I’m not trying to speak for Roscoe, but that’s where he’s at with it. We’re not just making shit up on the spot [laughs] that’s not a thing.

KP: Yeah, and for the latter part I know there’s some parts where you do stay silent with the Roscoe piece or the trio segments in LOW QUARTET but a lot of your stuff is kind of sustained sounding I guess to buoy up those harmonic interactions but when you’re thinking of stuff, how do you think of silence or deal with silence? In the other sense not so much it better be good sense.

JM: Well silence is something that… like when I was speaking earlier about dealing with the solo piece and that taking the form from isolation to an audience changes the form, one of the main things that changes about it is silence. If you want to circular breathe something forever, that is a strong decision. And you have to make sure that the musical information in that is strong enough to be sustained for that long. But also one of my favorite things in performance is when you’re in a room let’s say with like, when the room is full, and you’re at a performance, full house, and the performers choose to have this long silence and all the sudden you find yourself in a room with sixty or a hundred other people and everybody is just absolutely silent. That’s just one of my favorite things in the world. And then it’s something I learned from Sean, you know in the interview I did with him when we were talking about silence, you really have to feel the room and be engaged… when you engage with that silence you have to be extremely present with that silence and when you hear the room start to say like, alright this is enough, you have to find that comfort point with the audience. You know, some audiences might be so engaged let’s say you were planning on doing a thirty second silence and everybody was so comfortable that next thing you know you were silent for two minutes. A new piece I’m working on, a solo contrabass piece I have, there’s no circular breathing. And it’s because these silences - this is something I’ve pretty much taken from Sean, or learned it from Sean - is that silence makes the material so much more potent. If you have the same thing going forever and ever, yeah, you can kind of sink into the music and it becomes this universe that you can kind of float in. But if you really want it to punch you in the face, you need silence.

KP: Yeah to kind of hang on the notes, the tones, the sounds. I saw Sean I think five, six years ago, maybe seven, and yeah I wasn’t ready for it then [laughs] But even though I wasn’t necessarily ready for it it was still a powerful enough experience that it’s stuck with me five, six, seven years later and I haven’t been able to see him since then but now I love his recorded stuff….

JM: When’d you see him?

KP: No Idea here in Austin.

JM: Oh, in Austin.

KP: Yeah, yeah I think he’s come down here a few times but I really only moved to Austin in 2014 and started getting into this music then too. He ended up doing a solo cowbell set. And everyone’s kind of… it’s seated and everyone’s looking at the stage and then after a long quiet - and I guess people were aware something had started but I was not - he’s in a corner in the back and just starts hammering a cowbell creating these beautiful harmonics that I’m not super attuned to at the time and at the end it’s a very long silence. And at the time I was like, well this is kind of like a performance art thing, but I think gutturally the impact was enough to stick with me.

JM: Yeah that record of the cowbell music he’s been developing is coming out next month on I think Sacred Realism.

KP: Oh nice, looking forward to it. I’ll be able to finally reengage when hopefully I’m a little more ready [laughs]

JM: Yeah. Something I’ve learned from… two good friends of mine are Sean and Theresa Wong, the cellist, and they’re both so into microphones, well Theresa and Ellen Fullman as well. I’m always hearing about microphones and placement and rooms and all this stuff and it’s just things I never really spent much time thinking about. And now hearing… you know Theresa has an amazing solo record that’s gonna come out soon, she recorded a solo cello record that sounds incredible and then Sean’s cowbell record sounds amazing. So hearing those records after all this microphone talk I was like, OK I have to get my shit together [laughs] Because also it’s like if you’re gonna make a solo record, yeah, one way to do it is to go to a studio and book four days but if you’ve been developing something for months is one day really good enough to capture what you want to capture. It might be better to just get your own microphones and just record it a hundred times.

KP: mmhmm. Yeah the newsletter actually presented the notation for Harbors, Theresa and Ellen’s piece, and it was as much - and this is a bit of an exaggeration - but it was as much about speaker placement as it was about what’s happening on the instruments for those interactions to happen.

JM: Yeah they’re so into detail that it makes me feel like a caveman [laughs]

KP: [laughs] I’ve heard… the bassoonist Dafne Vicente-Sandoval is where I first heard about the microphones in the instrument, I don’t know, it’s always seemed super cool, also, very technical.

JM: Yeah, with the microphones and stuff like that I get a lot of Colin Stetson comparisons and stuff like that and it’s like, no this ain’t that.

KP: Yeah, there’s other people.

JM: Yeah, other people put microphones on wind instruments.

KP: I guess you’ve been talking about hearing what’s in your head and kind of thinking about Dafne, and I’ve been listening to a bit of Cat Hope lately too, who’s super into subtones, plays contrabass and bass flute, and both of them have worked with [Éliane] Radigue, who I know you’re a fan of, and I recently came across - I think it might’ve been her interview with Julia Eckhardt - but I came across some words from Éliane Radigue where she mentioned kind of like a preference for low tones. And I wonder if - I know you play a whole range, I know you play the clarinet family, I’ve seen some other winds popping up - but when you hear things in your head, does it tend to be those low tones, or is it easier to pick up on those interactions you’re dealing with in low tones?

JM: I don’t know what it is but I’ve always been drawn to bass. Always. Like my studio here is actually… this is like some picturesque Iceland bullshit but the ocean is right there. That’s right outside the studio doors. It’s a warehouse on a deadend road that sits next to the regional airport and so sometimes these big I don’t know carrier planes come in and just shake the building and it’s my favorite thing in the world. When I was teenager I bought a Pontiac Grand Am off my cousin. My cousin, he had a body shop so he was constantly like new cars, coming in and out. And I bought like a ‘98 Pontiac Grand Am or Prix, I can’t remember, I think it was the Prix, off of him. And it was lowered. All the windows were like illegally tinted. And the trunk was full of subs. And my cousin was like, I don’t know what I'm gonna do with this. And he gave it to me for like $1800. And it was the best time of my life driving around. I think at the time I remember listening to a ton of Outkast. The first big record for me, when I was a kid, was Aquemini, the Outkast record. And that blew my world open so big. I remember buying the CD from Target when I was in the fourth grade and the track “Rosa Parks” was big at the time. So fast forward I was always a big Outkast fan. In this car I have, you know, a stack of Outkast records and the first track from Speakerboxxx, the Big Boi solo record - it was the one where André 3000 and Big Boi did their own solo records together - the first track on Big Boi’s is made for like test-your-car-sound-system kind of thing. A few friends of mine would ride with me, you know we were teenagers and stuff, I had friends that were into tripping pretty hard, and they’d be tripping and would be like, can I ride with you. And I was delivering pizza at the time so I had friends that would ride in my backseat with me just to be sound massaged. And then I blew that speaker system with a Sunn record.

KP: Sun Ra? Oh, Sunn O))).

JM: I can’t remember which one, it might’ve been Dømkirke. No, yeah, I can’t remember which one but I turned it up as loud as it could and the tones are so [jamming interlocking fingers together] against each other that it fried the whole system. But yeah some of my favorite sounds in the world… like if you ever listen to… you know the Bob Marley and the Wailers album Babylon by Bus?

KP: I know it but I’m not familiar with it.

JM: Yeah so the version of “Concrete Jungle” on Babylon by Bus, Bob Marley’s bass player Aston Barrett on “Concrete Jungle,” that is the best bass sound that has ever happened as far as I’m concerned [laughs] And you know like Jamaican soundsystem culture is the coolest thing in the world. As much as I love low sounds, I wish I could go play through soundsystems in Kingston.

KP: Yeah the one time I saw… yeah Sunn O))) was not a comfortable experience for me [laughs] I was at least prepared with ear plugs, but the cartilage on my nose wouldn’t stop tickling because it was just shaking the whole time.

JM: Yeah, seeing Sunn… like I remember one time I saw Sunn at a small rock club in St. Louis, Missouri and I had ate mushrooms and you know they did the thing where like forty minutes before they play they fill the club with smoke. And this was a funny time seeing them because I was tripping but I couldn’t stop laughing the entire time, the whole performance was hilarious to me. And I remember seeing all these metal dudes holding up their phones and trying to take photos - and it was flip phones at the time - trying to take photos of them and everything is just coming back grey and I just remember laughing at that so hard like, what the fuck is the matter with these people. And the band that I was in, Tweak Bird, we did a tour of Europe one time where we were opening shows for Lightning Bolt, but this tour had the same booking agent as Sunn, so every venue we played we were a night after Sunn. So we would come to venues for soundchecks and they’d be cleaning up from the Sunn show the night before. And I remember playing in Manchester, England and we pulled up to this warehouse where the show was gonna be and you look up into this old warehouse and there’s giant orange Xs on all the windows. And I remember asking the sound guy like, did you guys just get new windows installed, and he was like, no Sunn played here last night. So they taped all the windows in the warehouse. And then I saw them in Oakland, that was the last time I saw them, in Oakland, California, and this time I knew what to… like I had high tech earplugs and I was up front ‘cause I wanted the whole experience and I remember walking out of, I forget what that place was called, I think the Metro Operahouse or something in west Oakland, and I took the earplugs out and it was the first time I had low ringing in my ears. Like a had a ringing in my ears of a low frequency and it scared the shit out of me. And I mentioned that to their sound engineer, and he’s like, yeah that’s not good [laughs]

KP: [laughs] Yeah that’s permanent damage. Unfortunately when I saw them it was outdoors, so I feel like I didn’t get the full experience of everything bouncing off walls.

JM: Yeah they’re definitely something to be seen inside, especially with all the smoke and stuff like that.

KP: When I saw them - I forget his name, but Agarth or Agartha or something [it’s Attila Csihar] - he was dressed in his robe and crown of mirrors.

JM: Yeah that shit is awesome.

KP: Yeah so I’m just imagining all your flip phone picture takers just getting reflections off that [laughs]

JM: You could wait twenty years and put that on a message board and be like, I saw this in the woods what is this [laughs]

KP: [laughs] I guess Sunn O))) is not a silent music but going back a bit to the silence bit - and Sean doesn’t do this - but there’s a portion of silent music where the stereotype is that there’s a lot of birdsong in it, field recordings, which I know you don’t have, but I feel like there’s a lot of birdlike sounds in the music. With your cupping technique, I wanna say you were actually using a birdcall with Roscoe…

JM: Yeah I used some birdcalls I have yeah

KP: Yeah and I know there’s also a bird tradition coming from jazz - and earlier in the conversation you mentioned tying music to geography so I wonder if it’s almost like a natural thing - but do you consciously involve birds in your music?

JM: Ah… what’s funny about those birdcalls when Roscoe and I played in Borealis was I think like a half hour before we played I was digging through my contra case and I was just like, oh Roscoe check these out, and he was like, oh nice. And I just kind of… I didn’t realize I brought them with me, they were just in my case and I was like, maybe these will be useful, and I just kind of sat them off to the side and then at a certain point in the set it was close to what I was hearing with what Roscoe was doing so I was like, yeah go ahead and do it. But I just got this, I’ll show this thing to you, hang on… you ever heard of a Garklein?

KP: No.

JM: Yeah, so, Garklein. A Garklein is a sopranissimo recorder. So this is a professional instrument [holds up recorder to show it’s the length of his palm] and it’s an octave above the piccolo flute. And I have like basketball player hands so this is bad but [blows some high frequency notes] you know, that’s the range of that.

KP: [laughs] And was that… it almost kind of looked like a jointed flute or something… that was a recorder as well at the Borealis show?

JM: Yeah are you talking about the bass recorder?

KP: Yeah it was angled…

JM: Yeah. It’s called a knick, like that’s what they call the angle. Bass recorder, yeah.

KP: A knick with a k? Like the basketball team?

JM: Yeah, I don’t know what it means.

KP: In rivers, waterfalls are technically called knicks. Bringing it back around to the beginning [laughs]

JM: Yeah I mean recorders are like this. Like sometimes like right now - you familiar with the guitarist Brandon Seabrook?

KP: mmhmm

JM: So I’m getting ready to go to New York for two weeks. I’m playing shows but mainly while I’m there, why I’m there is recording this album of Brandon’s compositions and I’m playing recorders and like all my instruments is what he wrote for. So I have some like virtuosic recorder parts and you know sometimes when I’m struggling… what’s really funny is when you’re fucking up practicing the recorder… dude…

KP: Still sounds great [laughs]

JM: No! You sound the most possible like a child like if you’re practicing and you mess something up it’s like, oh my god what the fuck did I take up the recorder as a joke? [laughs] But I really love the instrument because the reason I started playing them I think was that the amount of control and technique that the clarinet requires, the recorder requires just as much technique but it’s not as much the actual embouchure. Cause with the clarinet it’s all about like how you form your lips and all this stuff to get resonant sound and with the recorder mainly the technique is in the hands so I started playing as a kind of vacation from embouchure hell. And then you don’t get as tired playing it, so I would find myself playing Handel for pages and pages and pages and it just stuck.

KP: Whenever you brought up the bad recorder sounds, one of the songs that probably gets stuck in my head the most is the meme with the guy doing the Titanic song with the recorder [laughs]

JM: [laughs] There’s a whole Youtube page... I remember a band I used to be in, I remember we were coming home from a tour, we had played Lafayette, Indiana and were driving back to Chicago and one of us discovered I think it was called like shittyflute was the name of the Youtube page and so it was like “Toxicity” by System of a Down for like multitracked shitty recorders and yeah we were crying laughing going through… so yeah the Titanic version was like this shittyflute page.

KP: [laughs] So a few years ago it seemed like you were pretty honed in on the clarinet family but now you’re expanding out to recorders, is that just to give your lips a little reprieve or are there some other goals in expanding your toolset?

JM: I have no idea. But I’m an insane practicer. Like I don’t usually ever go a day without practicing unless it’s like Christmas or a travel day. So I practice the contrabass clarinet everyday because I have to always be moving forward with the instrument, you know what I play the night before the next day I have to revisit that and see what’s new. But recently with practicing all this Brandon music my practice sessions have gotten a lot longer and when I’m done I look around and all my instruments are out and on stands, like I’ve played every instrument I own. And I used to not do that a lot and now that I do it feels really nice, it’s almost like every instrument is like a friend of yours and you’re like, hey man what’s up what’s been going on. And so to… it’s just fun to play all the instruments. But yeah the contrabass clarinet, that’s my baby. I’m trying to talk to this German company… you know, the guy who designed the paperclip contrabass clarinet, he was a Belgian engineer, he did some math and just bumped it down an octave and so there are two octocontrabass clarinets that exist in the world, that are an octave lower than the contrabass I play. So I’m trying to talk to this German company who’s doing a lot with 3D printing and all that technology and I gotta try to find a way to get an octo contra.

KP: [laughs] nice

JM: Yeah the lowest notes on the instrument are felt not heard.

KP: So I’m aware that there’s the paperclip but then there’s also some straight contra clarinets. I’m not quite sure what the tunings are but does that do anything other than kind of lengthen the tube and lower the octave in a shorter way?

JM: All it was was a different way of designing the instrument. They just took a straight tube and wrapped it around itself to make it kind of easier, maybe for like marching bands or something I’m not exactly sure.

KP: Yeah and you just prefer that to the straight one?

JM: Yeah it’s just easier to play. You can sit down with it. And I mean also it’s really the only contrabass clarinet I’ve ever played. When I was doing my bachelor’s degree, I was in the clarinet studio at SIU and we had the clarinet choir which I think… I’ll go on record and say that the clarinet choir is the worst ensemble that has ever existed. Clarinet choirs need to be stopped. And so I had to play in this clarinet choir and the school had a contrabass clarinet that nobody wanted to touch and I was a big bass clarinet player at the time. That was kind of where I started, was bass clarinet. And then I just picked it up and never wanted to put it down. And also I had no interest in… you know there were so many clarinet players around me that wanted to be like first chair virtuoso traditional soprano clarinet ripping Mozart kind of stuff and I didn’t have much interest in that, so just looking at whole notes for pages where I could just sit in the low frequency, like my old grand prix with the Outkast record [laughs], I was like, oh alright yeah I’d rather do this.

KP: [laughs] Nice. That’s kind of what I had lined up but is there anywhere else you wanted to go?

JM: Lemme think. Yeah, new record coming out in the Fall, excited for it to be released. Some new stuff cooking up. Theresa Wong and I have been talking about doing a duo record for a long time. Oh, there’s another mundanas record that is finished… or it’s like I wrote all the music, composed it, recorded demos of it, and now it’s just a matter of me and Madison [Greenstone] figuring out when we can get together and have enough time to record it ‘cause it’s like an hour and twenty minutes worth of contra duos. It’s all contra and like an hour and twenty minutes worth of mundanas music.

KP: That’s awesome.

JM: Yeah I think it’s… you know I usually hate everything I record and I haven’t recorded this with Madison yet but this is kind of the most where I’ve been like, yeah I think I might like this.

KP: Well, yeah, the first set, was that with Madison in mind? Whereas with this it seems like Madison is in mind.

JM: Well, it was kind of half and half. I think I wanted to do clarinet duos and I think I had written maybe two or three at the time and I was trying to figure out… you know I needed to find a clarinet player that was a perfect kind of companion for the music. Because there was a lot of circular breathing technique, multiphonic technique, I needed somebody that was into this, I needed somebody that was a little bit of a glutton for pain because of the duration of it and stuff. And so I went to a concert in Oakland that was pieces by Jessie Marino, Natacha Diels, and Bryan Jacobs and Madison was performing duos with Bryan Jacobs, these pieces that Bryan did for mechanical clarinets that have like hydraulic pistons in 3D printed clarinets so they’re pretty much just blowing into them and the clarinet is just [mouths industrial noises] incredible. I met Madison there and I was like, alright yeah this is the clarinet player.

KP: Nice, yeah I was introduced to her through the first mundanas record but I’ve been paying attention to her with TAK [Ensemble] since then, she’s done some super cool parts there, and then I saw that she composed a piece that was played on some compilation recently.

JM: Yeah and if you want to check something out that’s really killer she just did Brian Ferneyhough’s clarinet concerto with the new music ensemble at University of San Diego with [Steven] Schick conducting. And it shouldn’t be humanly possible, it is for Madison. That’s how Madison and I differ, is that she can kind of do anything [laughs]

KP: [laughs] And I guess some time ago did you mention that you had some stuff coming out with Sean and Ryan Packard too?

JM: Uh, this is like the shit of being an improviser, is that there’s always records somewhere on a harddrive and you forget about them or… It’s something I’m trying to transition out of, yeah let’s get together and record, yeah let’s make an album that we’re really psyched about right now and then we’ll forget about it in a month. I’m really tired of that kind of world of improvised music. It’s one thing to be like, OK let’s make a record together. But this, hey let’s get together on Sunday and knock one out, I’m not about it. But there’s a number of improv records somewhere in my harddrive. Like yeah there was a record, actually really thorough, there’s a trio record with Sean and Barry Weisblatt that we did at ISSUE Project Room where we took… I think we did like four days in a row in the ISSUE space and left everything set up and I think we recorded like three or four hours of music and it’s just been extremely long email chains. This is the thing about improv records, this is the part that I hate the most, you will get to a point in an email chain where it’s like, alright yeah I think this is good, and then one person doesn’t respond. Seriously a year and a half later you get an email being like, oh just missed this yeah let’s do this. Like fuckin’ seriously? The window is gone. This music is too old now [laughs] And so that’s always bound to happen but that record will come out. I think Ryan and I have made like six records together with other people like Rob Lundberg, Andrew Clinkman that are somewhere on his harddrive and you know after a certain amount of time you just say, ah fuck it whatever. There’s also a duo record with Carlos Costa, the percussionist in New York, me and him made a duo record before I left New York. Like the last week before I moved out of New York I think I made like three or four duo records with people. The record with Jeremiah was one of those.

KP: Yeah, I’ve been enjoying that.

JM: That was a unique thing because we were at Pioneer Works and everything’s so streamlined and Jeremiah doesn’t fuck around with records, like he’s with it until it’s done. And it was one of those sessions that just felt really natural like it was one of those things where it felt like we couldn’t do anything wrong, it just felt natural and was flowing. So that was one of those where when we got done it was like you had a feeling about it like, yeah this should be an album so…

KP: Nice. I guess you said you mostly work at night, are you pretty much in your practice room from now ‘til evening?

JM: No, depending on if I’m not teaching I’ll do two sessions. I’ll come here during the day and do more focused, attentive work, like detail work. And then at night I’ll come back and kind of let the creativity flow. But yeah I’m here every night. I’m pretty much a nocturnal person. Roscoe put it a good way once. You know he practices in the early morning and I practice late at night and he was saying, yeah it’s perfect because no one’s up clouding the air with their thoughts.

KP: [laughs] Yeah he was an army player too right so I guess he got used to that routine, early rise.

JM: Yeah that’s something I hear a lot like when we were rehearsing and he was telling me something that he thought I needed to listen to he would say, John you gotta remember I’m an army man.

KP: Yeah, still an army man sixty years later [laughs]

JM: Yeah I grew up with a lot of army men so it’s not really anything new to me. So there was something I wanted to ask you, how’d you get into all this music? Are you a musician?

KP: Eh, I don’t have the rigor to put that title on myself. I played around with bass guitar as a kid but the structures, like learning how to read music, I just wasn’t into at all. Only honestly within the past couple of years… my wife… from the Jeremiah interview, she’s the opposite of Jeremiah, she loves shitty instruments and loves the variety, so she’s got lots of instruments lying around, and I’ve been messing around with her amplifier that has built in eq. And if I half-plug it’s input from it’s own output it creates a feedback tone that I can manipulate with the eq and volume and stuff. And that has no structure right, so I’ve been really enjoying messing around with that. But yeah not really a musician. I’ve always been into music, all my sisters were in their teens in the early ‘90s, and we kind of joke around that it was really kind of life or death for musicians in the ‘90s like if you look at radio music with all the ODs and suicides and stuff it seemed super serious on top of actually enjoying the sound, so just always taken music seriously. And I mean in college I listened to some stuff, like started with Kind of Blue, Coltrane, moved on to Sun Ra and stuff like that but when I moved to Austin in 2014 my wife took me to a Fred Frith solo. And just kind of seeing the music live and outside of the inside-outside paradigm of the ‘60s is what blew my world open and just started listening to more recent, more improvised stuff. And probably around the time we talked for freejazzblog my perceptions were so off I thought what you were doing was still pretty close to like free improvisation so I was in the deep end of the pool. Always in the deep end of the pool…

Read John’s first conversation with me here

JM: Yeah you were going whole hog.

KP: I think slowly I started to realize that a lot of what I was listening to was a bit of both, you know composition and improvisation, so then I started digging into more composer names, almost like networking in a jazz way right like hearing a player you like on a recording and then searching them out. I guess people tend to network in similar ways. So yeah just kind of found my way there.

JM: And yeah like maybe something about… I don’t know why that reminded me of that, but a foundational aspect of what I do now I’ve been able to… like the solo works for contrabass clarinet I’ve been able to link to my childhood 100% with how I lived with these acoustic phenomena in my childhood where I lived outside of a small town, I lived on a state highway leaving the small town. And my dad had his body shop, his autoshop, which was, you know, the garage was bigger than our house, and he specialized in muscle cars, he was a drag racer, so all these big American engines, that’s all I heard was just… I was outside all the time as a kid and in the garage so all I heard was the idling of these giant engines. And when you’re up next to ‘em or crawling up under the car as a kid and stuff it’s just [deep chugging sound] you know. And then also another cool aspect of this that I remember is laying in bed at night, and so the road as it came out of town went from like a 35mph road to a 65mph road and as it went out of town there was like a 90° curve right before our house. So I’d be laying in bed at night and you could hear a motorcycle leaving a bar at 2AM or something accelerating towards you. All you hear from far away is only part of the harmonic picture of the sound of that motorcycle. And as the motorcycle accelerates and gets closer and closer you’re getting the full spectral picture of the sound of that engine. And then as it passes it compresses again. You know, you get all the high overtones when it’s far away and then as it gets closer the bass tone creeps in, creeps in, creeps in, gets louder, hear the whole thing, and then it does the same way as its driving past. And so that’s all my music is [laughs]

KP: [laughs] So I've already written a draft of some of my thoughts for the Cymerman record and I think there’s a sound I recognize from your solo stuff too, or at least it’s similar, but there’s definitely something I’m hearing that I compare to a turning motor.

JM: Yeah and also when Jeremiah and I did that record, the solo record I have coming out in the Fall with Randall Dunn… yeah I didn’t even talk about that, you know who Randall is?

KP: Yeah the Sunn O))) engineer?

JM: Yeah. So to do a record with him I was like, yeah he knows exactly what to do with what I’m doing on this instrument. So when Jeremiah and I did the record together - and I met Randall through Jeremiah - I think I had finished recording the record with Randall like a day before the session with Jeremiah, so I was still in that soundworld. And I remember picking up the Bb clarinet for that session and being like, I haven’t played this instrument in like two weeks, this is stupid for me to be playing it. But yeah, you know, it was cool because Jeremiah has always been a big supporter of me and what I do so when I would lay down my thing he would know what to do with it.

KP: Yeah, that’s awesome. You were talking about motorcycles and I didn’t grow up by a highway but - people are probably familiar with it through Pauline Oliveros recordings or something, the cicadas in Texas - they tend to sing from tree strand to tree strand to you get like cycles of cicadas going through back and forth rattling for a bit and get that similar doppler effect. But yeah I don’t know if I can pin down in my childhood where I found an interest for sine waves [laughs]

JM: Yeah it’s just something about growing up in a rural area where as a kid when you find something interesting, I mean, that’s what you’ve got.

KP: Yeah. I do remember… my grandmother had a ranch and I’ve heard that La Monte Young listened to high tension wires a bit and got some inspiration from those and definitely when there’s the rare moment that you don’t hear birds or wind that’s definitely all you hear out there, that high tension hum.

JM: Yeah, and I think the most amazing musicians we have in the world are probably starlings.

KP: Uh… oh, yeah yeah.

JM: Yeah, the bird species. It’s like Peter Evans sped up eight times, that’s what starlings are…

Lemme see, I just wanna make sure that there’s not maybe something I wanted to talk about that I’m forgetting about. Just finished a new arrangement of a Roscoe piece for an improvisers orchestra in Prague that’ll be premiered next month. That’s another part of my work that has been happening a lot lately, is doing new arrangements and new orchestrations of preexisting works by Roscoe Mitchell. And it’s a really interesting way to do it because the piece is, Wha-Wha is the name of the piece. And so Wha-Wha was a track from Roscoe’s record Conversations, which was a trio with Craig Taborn and Kikanju Baku. So Wha-Wha was an improvisation, composition in real time, and then Roscoe had a former student of his, I believe his name was Stephen Harvey, transcribe Wha-Wha, and then Roscoe took that transcription and did a version of Wha-Wha for orchestra, which I believe had an improvising soloist. And then he got approached by this ensemble called PMP Ensemble in Prague and they just recently did a version of Anthony Braxton’s Diamond Curtain Wall Music. So they recently commissioned Roscoe and then I was given the task of taking the version of Wha-Wha for orchestra that was ten minutes and making it a thirty minute piece. So what’s interesting about this, you know I expand, and thankfully I have Roscoe’s trust, that he’s willing to trust me to expand this music. And then, like we did this with the piece for navy band, the Nonaah for concert band that we did in Norway is a similar thing. Where I took his version of Nonaah for orchestra, which you know you can take back to a solo piece for saxophone. And then afterwards you know Roscoe and I are talking after the Nonaah premiere and he’s talking to me about the ideas that he has for the next version of Nonaah. He got ideas from hearing the version we had just done. So it’s kind of the same way for this version for PMP Ensemble, is that I’m sure Roscoe will take this thirty minute version, which has an improvising soloist, Jon Irabagon, a great saxophone player is the improvising soloist on this version of Wha-Wha, I’m sure Roscoe will get ideas for the next version of Wha-Wha. So it’s always this constantly expanding… like you know the kind of phrase of the Art Ensemble of Chicago was this thing of ancient, present, future. Roscoe has this amazing ability to always exist simultaneously in the past and the future. He’s a remarkable guy.

KP: Yeah the Borealis thing was him playing with videos of his past, right?

JM: Oh his, yeah, and that was a learning experience for him. He talked to me about that, that he found himself following himself and would then have to restructure how he was approaching everything. And also playing with his dog, Shuggie, which I think is this remarkable thing because I used to have a black lab that would sing when I would play clarinet, only certain notes though, and you know he’s got this thing with Shuggie going on. And it’s this complicated thing because to me it’s an extremely interesting thing, to be improvising with, you know, not a human. For Roscoe it’s been improvising with people, then improvising with musicians like David Wessel and Richard Teitelbaum and George Lewis’ Voyager program and all this stuff, and then fast forward like thirty, forty years and you get him improvising with his dog.

KP: [laughs]

JM: Yeah and it’s this hard thing to talk about because I find it absolutely fascinating but you can’t talk about it without laughing. When we did the interview I tried to speak to him about it because I was genuinely… like when he started doing it he called me one night and he’s like, John listen to this, and he puts his phone down and he’s playing sopranino and I’m hearing like [dog moaning sound] and it was shortly after he had gotten Shuggie. And he was talking about how good of an improviser Shuggie was and so yeah I was fascinated. In the interview I wanted to talk to him about it but I could tell the audience was laughing as I was asking him about it so I don’t think he was too psyched to talk about it if it was being treated as humorous or something.

KP: Yeah I think that’s an amazing opportunity to have an animal that can do that. We have a dog but whenever my wife plays music she doesn’t interact. Sometimes we’ll put something on the speakers and if there are long silences in between sounds she’ll look up to see what caused that but she’s not vocal about it. I think so often, like when you get really deep into things… almost like me with Sean Meehan and being like, well this is performance art, and five years later being like, this is actually really amazing music… maybe a similar thing where if they go down that rabbit hole and start thinking about Shuggie again they’ll come back around to it.

JM: Yeah music is amazing like that. Sometimes you have to have a little more information. I remember hearing some Impulse era fire music from the ‘60s and thinking like, oh jesus christ, and years later coming back and having an understanding of it. To have a full understanding of the structures and forms and to know what’s going on and all that stuff… oh yeah, speaking of Roscoe the next issue of Sound American is The Roscoe Issue.

KP: Oh nice, well, uh have you been commissioned for an article?

JM: I’m… there’s gonna be multiple interviews with him and I don’t know who’s signed on but I’m gonna do one of the interviews with him and I’m gonna work it out with the other interviewer so we don’t have much crossover. ‘Cause there’s a lot of his career that doesn’t get talked about, you know. His interviews are all around like what is the AACM, what was it like when the Art Ensemble moved to Paris, and Nonaah. That’s what he gets asked about and he’s eighty-one years old and has done so much. So there’s so much to talk about with him.

KP: Nice, looking forward to that.

JM: Yeah and the music I make is directly linked to what he does. The long durational stuff. It’s like yeah I learned that… I was developing this before I came to him but hearing him and how he deals with music… yeah, I owe a lot to that guy.

KP: Yeah… I actually saw Eric Mandat play a New Music Circle show in St. Louis earlier this year.

JM: Oh, Eric Mandat. Wait, you were there?

KP: No, it was like a streamed show.

JM: Yeah he was playing with that pianist friend of his, I forget his name.

KP: Yeah I forgot his name too [it’s Greg Mills].

JM: Yeah Mandat and I, we have a solo/solo/duo show at Roulette in New York in October, so I’ll play solo and then Eric plays solo and then we’ll play duo. And I mean you were talking about like, when you were talking about your own musical trajectory and finding reading music intimidating and that kind of thing, that’s how Dr. Mandat hooked me up. I had recordings of bass clarinet solo pieces I was working on and he transcribed them for me to show me how notation worked. So I had an ear reference for like, yeah you wrote this so you should know how this works. He pretty much taught me to read music as like a twenty-one year old or however old I was.

KP: Yeah I heard y’all touch on that in the Cymerman interview with the wrecked bass clarinet.

JM: Yeah that was... when you don’t know then you don’t know. It’s broke so you better fix it. It’s not just like, oh get a new one. What do I have around to fix this. But yeah that’s about all I know.

KP: A lot of fun stuff on the horizon.

JM: Yeah because of the record coming out in the Fall I’ll be doing a lot of touring around. That’s also a nice thing about living in Iceland… you know, living in New York City has its pitfalls, which is you don’t leave… or its hard to leave because people are so financially strapped living in that city. But here it’s nicer to kind of be like, oh OK let’s see what’s happening in Copenhagen, OK let’s see what’s happening in Stockholm, let’s see what’s happening in Bergen. All that kind of stuff so you can actually go and be in different scenes instead of like, OK tonight I’m going to go play in Ridgewood, tomorrow I’m gonna play in Bushwick, you know [laughs] Yeah, it’s a benefit. But hopefully I’ll come to Austin at some point. I was there for SXSW before the pandemic hit.

KP: Oh OK, yeah, please do. Lemme know if I can help in anyway. I’m not really an organizer but I can try and hook you up with actual organizers.

JM: You guys got Nate Cross down there.

KP: Yeah Nate’s here and then Nate works with a couple of local organizers too pretty frequently but yeah… I forgot that you released some stuff with Nate so I’m sure he would be glad to have you down.

JM: Yeah the new record is co-released by Astral Spirits. It’s a split between Astral Spirits and Dinzu Artefacts that new label out of LA that released the Jeremiah record. So it’s a split between them and then the art for the record was done by this incredible Icelandic photographer named Vidar Logi, he’s mainly like a fashion photographer but what we did for the cover, I’m excited about it.

KP: Nice. Well, I’m excited to hear it.

JM: Yeah this is the most contra it gets I think.

KP: Any time someone says that they’ve gone off the deep end that’s my cue to listen.

JM: This record is like… stepping away from it I was like, alright, it’s too deep [laughs] I sent it to a friend of mine, actually sent it to two friends of mine who were like, John I’m gonna be honest with you it felt paralyzing. I was like, I don’t know if that’s good or not. But it’s something.

annotations

annotations is a recurring feature sampling non-standard notation in the spirit of John Cage & Alison Knowles’ Notations and Theresa Sauer’s Notations 21. Alternative notation can offer intuitive pathways to enriching interpretations of the sound it symbolizes and, even better, sound in general. For many listeners, music is more often approached through performances and recordings, rather than through compositional practices; these scores might offer additional information, hence the name, annotations.

Additional resources around non-standard notation can be found throughout our resource roll.

All scores copied in this newsletter are done so with permission of the composer for the purpose of this newsletter only, and are not to be further copied without their permission. If you are a composer utilizing non-standard notation and are interested in featuring your work in this newsletter, please reach out to harmonicseries21@gmail.com for permissions and purchasing of your scores; if you know a composer that might be interested, please share this call.

Hannes Lingens - Five Pieces for Quintet (2013)

Hannes Lingens is a composer, performer, improviser, percussionist, and accordionist whose music might focus on choice at the convergence of interpretation and improvisation and group dynamics, not just of performers but composers, listeners, and others too. Among shared projects and named groups like Konzert Minimal, OBLIQ, Die Hochstapler, and Musaeum Clausum, some frequent collaborators include Félicie Bazelaire, Sébastien Beliah, Pierre Borel, Antonio Borghini, Louis Laurain, and Derek Shirley. And some recent releases include Music for Strings with Bazelaire and ensemble CoÔ, Riebeckplatz with Borel, Borghini, and Laurain, and contributions to Borghini and Alexis Baskind’s When Will Never Meet. Lingens is also part of the Umlaut Collective, associated with Umlaut Records.

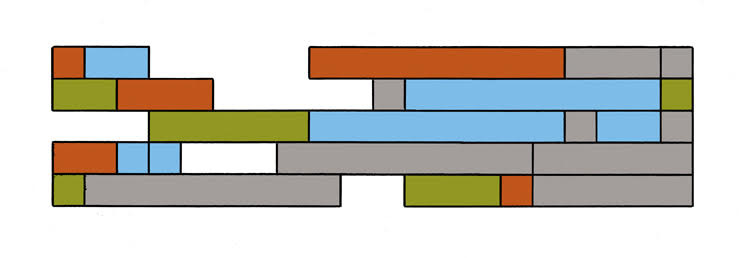

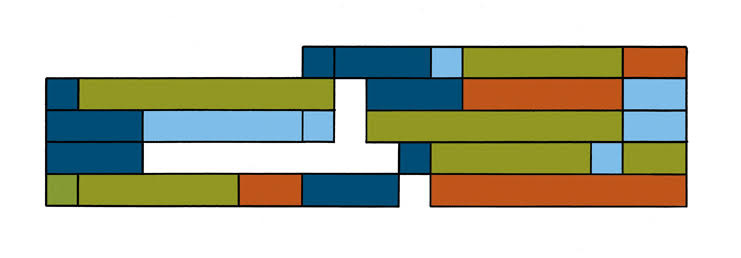

Five Pieces for Quintet is a 2013 series of compositions. Beyond specifying five musicians in the title, it comes with no instruction. Duration, instrumentation, pitch, and other materials are open. Each graphic is five rectangles of equal width segmented into one of five lengths filled with one of five solid colors (not including white). Each piece includes four of five colors. Segments of the same length or same color frequently abut horizontally and vertically.

Perhaps each musician plays a horizontal and the group chooses sound material with similar pitch, texture, or cadence for color signifiers and relative sounding duration for segment length. Or plays a color, overlapping rectangles of the same color indicating relative pitches on a chord, segment length again sounding duration, and a fifth player can mime the void spaces if the group feels everyone should play each piece. Or plays a segment length, placing time on the y-axis, setting united sounding durations, and again choosing material corresponding to colors. Perhaps each musician interprets the whole graphic of a piece for the performance of that piece. Perhaps each musician interprets a separate piece so the quintet may play the whole series at once. The possibilities are as limitless as the imagination of the musicians. In indicating only that five people come together to realize it, Five Pieces for Quintet requires the creation of a shared language together and prioritizes the process of exploring personal relationships and community coding over any sound result. But choices have consequences. And the group must navigate not only the changing interdependence of musical parameters in their chosen set of interpretive rules but whether it is possible to realize those rules with the instruments they use. In this way it encourages a mutual care during preliminary decision-making and its unfixed, relative color and shape relationships encourages that care during play, necessitating active listening and interaction to stay true to its largely open form.

The realization below features the composer on accordion with Johnny Chang on viola, Koen Nutters and Derek Shirley on contrabasses, and Michael Thieke on clarinet, who have chosen to continue the motif of fives through piece durations. The notation and an insightful interview with Lingens on his approach to composition and realization accompanies physical and digital copies.

reviews

Ryoko Akama & d’incise - No register No declare (INSUB., 2022)

Ryoko Akama and d’incise perform an Akama composition with recordings, EMS synth, and no-input mixer on the 18’ No register No declare.

Overlapping alternating relationships of similar timbres. Dripping water blends with frying oil, a metronome blurs towards tapping, electric hum or feedback, a plastic crackling from static, clicks and bumps, recorded time and time recording. Silences whisper sounds. The lisps of air indicate spaces but their parameters, shapes, material, moisture, temperature, entire characters remain mysteries. Ambiguities reveal the unreliable narrator of the inner ear. A tactile experience out of reach. It ends like it continues and maybe it started that way too, a moment of heightened awareness of the everything in the nothing around you.

- Keith Prosk

Leila Bordreuil, Biliana Voutchkova - The Seventh Water (Relative Pitch Records, 2022)

Leila Bordreuil and Biliana Voutchkova play four duologues for cello and violin on the 35’ The Seventh Water.

Through counterflows, longer and shorter durations, viscous gliss in reflected directions, low and high registers, polyrhythm, strings expand similar textures together for engagingly strange harmonies. Train horn harmonies with rail squeals. Barely-there breath of bowed bridges and massaged bodies. Birdsong in chirruping screech and divebombing bowings. Taps and pizz ring like bells and shells in webweaving arpeggios. Convergence only occurs through difference. And I hear the textural techniques and noise of each conjoined for a shared communication.

- Keith Prosk

Jeremiah Cymerman & John McCowen - Bitter Desert (Dinzu Artefacts, 2022)

Jeremiah Cymerman and John McCowen play eight tracks for Bb and contrabass clarinets on the 39’ Bitter Desert.

Cymerman’s skill for conjuring bleak moods through somber sound but context too - these titles might suggest darker corners of NYC history - has an apposite foil in McCowen’s bone-rattling drones and hostile textures. They move in contrapuntal coils, leveraging their divergent registers and wavelengths, the jokulhlaups ripples of contra and ululating undulating of Bb, through smoothed and distorted tone surfaces and complementary spatial placements. Slower circular Bb melodies accentuate the slinking slurred articulation clarinets can have. And Bb duos imagine intertwined snakes in their charmed movements. From an otherwise austere languor emerges other voices from the menagerie, stridulating harmonics, turning-motor purring, an exotic aviary of multiphonic chirpings and cupped hand calls. The apoplectic panic of arhythmic fingerings, death gurgle glissandos, overblown squalls. Like animals twisted by the soundscape around them.

- Keith Prosk

gabby fluke-mogul - LOVE SONGS (Relative Pitch Records, 2022)

gabby fluke-mogul fiddles sixteen solos for violin and voice on the 35’ LOVE SONGS.

Along with songs’ short lengths, melodies of a fuzzy familiarity form an impression of tunes, a nagging feeling say “IIIII” or “IIIIIII” is just out of recall’s reach when “you are my sunshine” reveals itself from “IIIIIIIIIIIIIIII.” Cadences kneaded like clay. Fragments repeated not with systematic variation but the natural rejuvenation of their relation to each other in series. Twisting bow and playful pressures explode pitch clarity for emotively expansive textural spectra. Extensions of resonant arco, pizz with its bent notes and sunny strums is rings deep too in its decay and the yawp of voice complements the coarse chords of violin, even beating together in true harmony at the end. There is a sense of joy because there is a sense of play, and all together it reminds me of the spirit of Ayler.

- Keith Prosk

Cat Hope - Decibel (ezz-thetics, 2022)

The Decibel ensemble performs five Cat Hope compositions with viola, cello, contrabass, flutes, reeds, piano, percussion, feedback, and subtone on the 51’ Decibel.

“Majority of One” is strings and winds sustaining states of strange suspension in gliss that emit turbine beats in deep harmony whose rhythm and melody is a function of breath and bow more than any other material. The gatling dexterity of piano player and player piano can blur together in “Chunk” but more than the inhuman endurance and speed of the latter the former’s human articulation in finessed pressures delineates the two. Silence separates bars of chaotic action, strings’ seismographic squiggles and stippling pizz on a canvas of reverberant piano glow and heavy metal electric tone, a kind of density that feels like finding meaning in abstract expressionism, in “Juanita Nielson.” Among body sounds and plucked interludes, the cello arco of “Shadow of Mill” beats and drips and ripples within a quaking subtone whose contours seem to conform to those of the cello, their interference wrinkling perception. And “Wanderlust” is a sound walk with steps in steady cadence, rhythmic winds, bird song, conversation, motors, and wheels in which patterned moments reveal patterns in other material that might otherwise feel aleatoric. While these touch on the composer’s chosen materials - aleatoric elements, drone, noise, glissandi, and low frequency sound - each also focuses their human element, locating the limits of the body or the mind.

- Keith Prosk

Decibel on this recording is: Louise Devenish (percussion); Cat Hope (flute, contrabass, composition, artistic director); Stuart James (piano, composition, programming, sound design); Tristen Parr (cello, production); Lindsay Vickery (reeds, composition, programming); and Aaron Wyatt (viola, IOS programming).

Jason Kahn - Lacunae (a wave press, 2022)

Jason Kahn plays two short sets, one show, one studio, with modular synthesizer, mixing board, voice, electromagnetic inductor, piezo microphone, radio, and environmental recordings on the 50’ Lacunae.

Anonymous nervous movements. Crackling static. Clipped transmissions. Knobs modulating electric whoops and hollers. Talking intonations from pinched and pulled wires. Feedback click tracks in phasing galloping and screaming sonar songs. Beep melodies and morse beats. Jolts in volume and frequency. The airwaves carry the symphony, pop pulses, radio drama. In hushed moments hear current hum, feet across the floor, creaking chair. The instrumentation is a complex system that nearly realizes an illusion of being just radio, something familiar and unpredictable, local and global, abstruse and vulgar, a copy of a copier, doubling down on its interesting ambiguities.

- Keith Prosk

Phil Maguire - Rainsweet Stillness (Minimal Resource Manipulation, 2022)

There were a couple things that stuck out to me as interesting from the bandcamp description for this album. The first is largely what inspired me to review this release – a quote pointing the album’s inspirations towards the early music of Richard Chartier and his LINE imprint. In the early 2000s LINE was publishing some of the most exciting and radical music in digital minimalism – slow works exploring silence, limited frequencies and the various limits of aural perception. On top of the innovation, it’s some of my favourite and most replayed music. I would have been content to hear an uninspired homage to this music that I love, but on Rainsweet Stillness I was happy to find much more (or perhaps less?) than that.