1/14

conversation with Christina Carter; notation from Bruce Friedman; reviews

Borealis Festival happens March 16-20. Some of its discussion panels will be streamed on the festival site, including Yulan Grant on mythmaking and remix culture, Khyam Allami, mattie barbier, Catherine Lamb, and Weston Olencki on rational intonation, and John McCowen and Roscoe Mitchell in conversation. Some of its performances will also be streamed on the festival site, including Ensemble neoN/Far East Network/Lasse Marhaug and Roscoe Mitchell/John McCowen.

$5 Suggested Donation | If you appreciate this newsletter and have the means, please consider donating to it. Your contributions support not only the regular writers but the musicians and other contributors that make it possible. For all monthly income received, harmonic series retains 20% for operating costs, equally distributes 40% to the regular writers, and distributes 40% to musicians and other contributors (of this, 40% to interviewee or guest essayist, 30% to rotating feature contributor, and 30% equally to those that apprised the newsletter of work it reviewed). For the nitty gritty of this system, please read the editorial here. The newsletter was able to offer musicians and other contributors $2.90 to $7.74 for January and $1.57 to $2.10 for February. Disclaimer: harmonic series LLC is not a non-profit organization, as such donations are not tax-deductible.

conversations

Christina Carter plays with voice, visual art, and poetry. Over video chat we talk about her voice, the body, rigor, money, art, complexity, changeability, relational experiences, and words.

Christina recently released Offer and Two Times and reissued tongue and Seals. The accompanying watercolor booklets we talk about in this conversation can be purchased on her merch page.

Christina Carter: Hi. Can you hear me?

Keith Prosk: Yeah! Can you hear me?

CC: Yeah.

KP: Nice. How’re you doing?

CC: I’m alright. How’re you?

KP: Good. It’s been a long time.

CC: Yeah, a couple of years. Unbelievably, right?

KP: Yeah. Have there been some musical upsides in the last couple years or…? I know Me Mer Mo started back up but it seems like things have been pretty quiet.

CC: Musical upsides… I guess it was inevitable but maybe it sort of like pushed me a little bit further to - sorry my chair’s really squeaky - to start putting older music that I’ve done online, on bandcamp.

KP: Yeah I saw that you’re putting some mid-2000s, small run CDrs up on bandcamp?

CC: Yeah. Basically my plan is to put up one older release per month for the rest of the year.

KP: Nice.

CC: So those will span 2003ish to 2013ish, and then, yeah…

KP: And are those… at that point is it mixed guitar and songs or what are you doing on a lot of those?

CC: Yeah. There are some that are just voice, some that are extended pieces with guitar, some that are songs, so all of it. I’m trying to think…. there’s some live recordings maybe… I haven’t decided entirely what will be put up and what won’t. Or if all of it will eventually, or… I’m kind of doing everything by feel as it goes.

KP: Yeah. Would you say that with the music you’re making now, do you tend to focus on voice? Or at least is it in a more vocal part in the cycle right now?

CC: Yes. I’ve been focusing on voice probably since 2015 at least. I mean for solo stuff. Of course I’m still playing with Tom [Carter in Charalambides]. I’ve been doing just voice in that too. I haven’t been playing guitar at least for awhile live. And even on our last recording.

KP: Yeah I was gonna say… I just moved to Austin in 2014 and the one time that I saw you perform it was solo voice, and then I heard maybe a phone recording with Alex [my spouse] and it was voice, and then you just put out Offer and Two Times, which are voice as well, so I kind of got that feeling that this was what you were interested in working with at the moment. That’s kind of why - and I’m glad to take it in any direction you want to - but I wanted to learn a little bit more about how you approach voice too, with this convo.

CC: Yeah, sure. I’ve been thinking of the last time I played guitar live... I don’t write anything down really or save records of what day I played, what shows, flyers, I don’t have a list, it’s all by memory, so I’ll probably get some stuff wrong. I think the last time I played guitar live was opening, playing a show with Michael Morley and I had decided to do half voice and guitar, half voice only. I think that was around 2015, -14, -16, something like that. And based on that experience I just was so happy to do the voice half more so than the guitar half. I was struggling with playing guitar live the whole time, or had major ambivalent feelings about it, so I decided I’ll just leave it behind for awhile.

KP: Yeah, until you’re ready to go back to it…

CC: [winces]

KP: or maybe not [laughs]

CC: I don’t know. I mean things are so up in the air in every single way as far as doing music now. I don’t know what will happen. Just recording is in question, playing live is in question, how to continue any of it. I think not just for me but for a lot of people.

KP: mmhmm. Do you still play guitar? Or do you still own a guitar and play privately?

CC: I don’t play. I do own guitars. I never was a practicer. I’m not a practicer. So that’s not in and of itself unusual. After a certain point… when I first started playing guitar I played, for me, kind of a lot, regularly, but I got to a point where I didn’t want to anymore, so I stopped.

KP: Are you comfortable with sharing the reasons why you’re more comfortable with voice over guitar?

CC: Yeah, there are multiple really. Everything from really silly kind of just, you know, inconvenience…

KP: [laughs] carrying amps

CC: Yeah, all the way to like social reasons and et cetera. I don’t have this music work ethic. All that like, ah I’ll carry my own stuff, show how strong I am, all that kind of thing, I don’t care about that. But it’s your instrument so you want it with you, well there’s people who really want it with them and that’s great for them, I don’t have any problem with that, but personally I don’t like… it kind of gets in the way for me, like of my mind, the whole get the gear together, set it up, do the sound check, on and on. It gets in the way for me. Sometimes it’s tolerable for me and sometimes it’s not. I just go with how I feel. So it’s more than just like they’re heavy; they take a certain kind of mindset to engage with them. I don’t know, there’s people who just love doing all those things. Great, I don’t. All that string changing, tuning, paying attention, all that gear, knowledge that’s good to have. I mean, it goes all kinds of ways, it’s so intense and ridiculous at times, but there’s truth to it, knowing those things, it’s helpful, the reality about equipment, knowing it, what’s good equipment, there’s a reality to it, not that it’s not based on nothing, it just gets in the way for me.

KP: Yeah, I imagine too, being someone who is attuned to using their voice as an instrument, instead of coming directly from the body you now have this filter with its own set of limitations and everything too with a guitar set up.

CC: Right, there is that. It makes you conscious of something else that’s on you, around you. It makes me feel like I’m interacting with the sound people in a different way. There’s a certain amount of uncomfortability with the tension of performing in front of people where I lose… it’s like what are you dedicated to, you know… I lose my confidence about playing guitar with people staring at me. Can’t do things that I can do in private in public. Unless there’s been various times, on tour maybe, getting to play night after night, but then I ask questions of myself like, is that worth it for me. I don’t consider myself a musician in the same way that other people do, at the same time I don’t consider myself… it’s not that I think musicianship is bad or that no one should have that pursuit, I’m just not that. That’s not my primary desire, to master the guitar, in any kind of way besides how I want to reflect my inner feelings. It’s hard to explain, and I could have that conversation for like five hours, to get into all the fine details of thought or whatever. But I don’t like the idea of people saying that I have no care for technique, that’s not true, at the same time that’s not where I’m going with it.

KP: Yeah, there’s other techniques than dexterity, right.

CC: Dexterity, theory, composition, et cetera, learning those things in a systematic way and wanting to… I admire people that can do that for sure, it’s just not me. I can’t, I don’t want to, I don’t want to because I can’t. I don’t know, it’s been that way since I was a child. And then I didn’t have much opportunity for lessons, so there was that, but also I didn’t want them. I mean I’ve said it before, I had one guitar lesson and I walked out on it. I guess everything… like swimming, I didn’t want swimming lessons, I was just like let me get in the pool I don’t want to learn how to swim I just want to be in there.

KP: [laughs] yeah, just that structure, or overstructuring.

CC: So anyways it’s like guitar, well I miss it sometimes, but also there’s all kinds of things that go into it, like money. I’ve never had money to buy a lot of equipment. I don’t want to. But at the same time, just the guitar setup and taking care of it and having a place to play it - I live with other people all the time, so…

KP: Well, we’ll leave guitar behind and if it’s alright with you…

CC: Well there’s no end so it’s not like, oh now I’m never gonna do guitar anymore, I don’t know, maybe I will.

KP: Yeah, yeah, just I’ll switch over to voice and not bother you with guitar anymore. So one of the things I felt with the two most recent ones - Offer and Two Times - was that it was kind of iterative. Not just that one was recorded right after the other, even though they’re quite distinct, but that within each they’re progressing through repetition. I feel like there’s a kind of empathy because the voice might be such a familiar instrument to others that there’s a kind of understanding in the listener that even though sounds could be intended to come out the same they feel different in the throat and come out differently. And then maybe going back to what I’ve heard of Charalambides with psychedelic tinges, there’s a hint of psychedelia in that inbetween state of something that feels continuous because it’s repeated but also recognized as discontinuous because it’s discrete soundings that are changing. But is repetition or iteration a conscious aspect of what you do with your voice?

CC: I was thinking about having this conversation with you and you were saying up front you wanted to concentrate on voice so I was trying to think about like, OK well it’s not like I’ve done a whole lot of interviews recently but I’ve been doing them for a long time so how can I talk about this differently this time. I was thinking about how the whole thing about the voice being integrated… your instrument is your body. It’s something that’s so fundamental it’s overlooked a lot. Like what is there interesting to say about that, yeah, it’s your body. I don’t even know if this answers your question, but I was thinking about how my weird relationship to it… you said empathy, or sympathy?

KP: Yeah, empathy…

CC: …and I wanted to ask you what you meant. I was thinking about how it’s such a weird thing that I - again it’s not that I think other people don’t have legitimate ways of doing it although I do question a lot of overemphasis on the technical aspects of singing - I don’t do any of that stuff. I don’t come from a musical background, my family didn’t do things. I didn’t have this kind of childhood maybe a lot of people a little bit younger than me are used to with a lot of hobbies, you know, you’re made to do a lot of things and learn a lot of things and be a multifaceted person. I never had voice lessons. I don’t do exercises. I was thinking, OK I’ve talked about that before. I think people get…I worry sometimes that some people who maybe would feel really great about singing don’t believe they are capable or they need supervision and lessons and a plan and a linear path. First you do this kind of singing and then you do that kind of singing and then you learn these kind of exercises and then when you’re ready you practice a lot at home by yourself and make sure you have a good enough voice and then you go out in front of people and then… that kind of thing. I don’t believe any of that is necessary. Maybe it is for some people. Maybe people feel good when they do that. I don’t. Never did. My thing is so weirdly internal and I was thinking why is that. And it made me think about how the body is such a place of contradiction. For me it represented a lot of pain and difficulty. My mom was an asthmatic, she was allergic to almost everything. I saw her get ill to the point of fear quite a lot. This was before inhalers and before modern asthmatic treatment, and I know it’s still bad. This was like breathing into a paper bag and hoping there’s no trip to the hospital and that kind of thing. My dad was also kind of ill, in a way. He had a lot of health problems, though he was better at hiding them. And I had, when I was younger, had endometriosis. Horrible pain every month, for years and years and years.

KP: Sorry, what is that?

CC: It’s a reproductive system… when you get your period you get horrible pain. Coincidentally my mom also had this and she had a hysterectomy, and that’s why she had to adopt me, because she couldn’t have kids. Also my mom struggled with her weight quite a bit, and we didn’t have physical activity as a family or anything. So, I think a lot… I found this other, this realm inside of the mind instead of in the actual physical body to be way more attractive and way more compelling, way more less problematic. And then appearance and all of that and that whole struggle with being a performer and being on stage. When I was a child I adored Judy Garland and one of the first things I wanted to do was be an entertainer and I use that word, and that’s such a funny thing to think about. But then when you go along or I went along, when I started singing first with Tom - I mean I was singing all along as a child by myself but - there’s a whole struggle involved with it that your ingenuity, your creativity… how to confront and deal with all the challenges of being a human being, creative human being, that’s what guides me so… once you start applying conscious or philosophical thinking to singing and all of these issues and then that adds another layer over all of the instinctual things, the feeling of singing. To me it feels very strange to sing, but also I felt very driven to do it from a very young age.

KP: mmhmm. So I guess with the… you’re not consciously trying things out when you’re singing, you’re really just going by the feel of the moment?

CC: I would say it’s intertwined. There’s a feeling of the moment, there’s that part. And then there’s an observer, who is evaluating and kind of thinking about it. There’s a multilayer thing right. There’s a receptive aspect. What’s gonna happen, I wonder, I don’t know. Wherever you are there’s a feeling in the room around you. There’s a feeling of the structure, the room, there’s a feeling of the air, all the objects inside of it, your memories when you look around, if it’s a new place then there’s your first impressions. There’s that part, that’s very receptive. Then there’s the desire part of wanting to interact with that, with those impressions. This active feeling of what do I want to do with this on a really kind of… you know it’s almost kind of an animal feeling, like when you’re hungry and want to eat something. An energy that draws you toward doing something.

KP: mmhmm kind of look in the fridge and piece together a meal based on what you’re feeling at the moment…

CC: Then there’s another level of evaluation, while it’s happening. OK what is going on, what is my desire leading me to do right now, what do I think about that? Do I find it compelling to go further in that direction? Do I need to find some other path? Do I need to make a turn? Am I going to continue? And so those three things - at least - are happening all the time. So it’s not random. There’s an intellectual component. There’s two kinds of intellectual components too, like the in-time evaluation about what’s actually happening and then the more aesthetic interpretation of like, OK maybe this seems like, I’m reacting to this feeling, I’m liking how this feels, I’m liking what it sounds like, but do I really agree with it aesthetically.

KP: On that observation side, do you find yourself returning to ideas or wanting to go back to ideas and wanting to explore them a little more, not necessarily in one performance but across time?

CC: Yeah, absolutely. I consider it like, and maybe it’s a cliche way of describing it, but it’s kind of like a map, or a larger image. And then maybe, you know, well I wanna go here for awhile, really close in, now let me look back at the bigger picture, now maybe over here. It’s all interconnected. But you think about things in different senses of time and space. And sometimes you take a more radical move, from one edge to the other maybe.

KP: Yeah, a little reactionary…

CC: Well, no, nothing wrong with it. Just instead of traversing the surface slowly and taking small shifts maybe sometimes you take big shifts.

KP: I guess in returning to some of that stuff or exploring it a little more, are you able to nail down some of those interests that you do return to?

CC: I hope not. I don’t ever want to really nail anything down. I don’t, you know… Sometimes it’s easier for me to write things, because I can think and evaluate what I’m saying, does it really explain what I mean, are these words the right ones. What I really want to do is reflect the truth, that’s it. So in other words, that my music reflects everything possible, considering the medium, that it can express about what it is really like to be a human being. As an approximation it’s impossible but I don’t want to convince anybody about anything or present an argument for one particular aesthetic sound or view or whatever, one type of music. I want when somebody hears what I’m doing for them to feel complexity. You know I was thinking about this earlier, sometimes you need to make a clear statement in your life, yes or no, about certain things. It’s necessary and it’s a good thing to do and that’s part of the complexity, right. But much of the time of being alive is grey, like happiness. Unadulterated happiness, no other shade of any other emotion in there, how often… I mean at least me, I don’t experience that very often. I have, but usually there’s a lot of other feelings wrapped up with it. Even if they’re just different shades of similar emotions like excitement. Excitement’s not quite the same as happiness, so… that’s the kind of ideal to me about doing music. And has always been. And always is. Even when I’m doing things that other people call whatever, psychedelic rock, psych folk, whatever other name it’s been called. That was a big turning point for me… and also it’s not biographical, I… Everything I think about is a combination, so… in that sense I never want to nail anything down. I’m trying to make something much larger than any one thing.

KP: Yeah, I agree that we’re all more or less spectrums and walking ambiguities and that sometimes just expressing the body expresses a complexity that is… I don’t want to say effortless to put it down but there’s so much complexity within us that if it’s just expressed then that can be complex in itself. One of the other things I picked up on is there are moments in Offer and Two Times that are very quiet. And when it is quiet you hear breath and cheek sounds and saliva and stuff like that. It makes it very clear that it is the body of a performer, that it is not a disembodied sound. Is that a conscious inclusion as part of that complexity, or is there a particular reason that you’re drawn to including that spectrum of the voice?

CC: Well because not including it would entail one of a few things. It would entail either having certain kinds of equipment, setting up the equipment in a certain way, doing the recording a certain way. Or it entails going behind it and editing it out. Both of which I don’t… most of the time I don’t want to do.

KP: Yeah, the first is that kind of gear filter like the guitar and the second is that untruth that you were talking about earlier in a way.

CC: Yeah. I mean there are certain things, like really egregious things, that I might think about removing maybe. I think on… I can’t remember which one but there was one sound that was edited out, but it wasn’t my body sound, it was something else in the room. That question about returning to different things, it’s not that… like the idea of repetition and variation and distinction between sounds is important to me. I am in fact trying, particularly in these two recordings, trying execution of similar sounds with slight variations in the shape of the mouth and things like that. I didn’t think about doing that before I started recording though, it started to happen, then I noticed it, then consciously began playing with it. That’s the thing, a lot of this is kind of play. As in, you know, like manipulating something, right. Like if people, when people throw a ball, they don’t throw it in exactly… maybe…

KP: [laughs] expert ball thrower

CC: Yeah, like super expert pitchers or something. Maybe they don’t though, I don’t know…

KP: No, they’ve got the box, right.

CC: Part of the amazement of it comes from this super attention to slight differences and what they convey. Because it’s not like to me, oh that’s cool it’s a different sound, I’m like a machine, look at the different sounds I can produce. They all convey something slightly different emotionally, or a slightly different concept. But then that gets into the realm of what I was talking about, evaluating it on a philosophical or an aesthetic agreement kind of level. On the one hand I think all of those kinds of things are interesting and on the other hand I think I never want what I do to be focused on those types of issues or ideas or techniques to the exclusion of what’s important to me, which is the emotional and intellectual content, intellectual as in thinking, as in human, reaching another person. Or reaching another… like contact. Relational. It’s not a display. Or a performance for people. It’s relational. It’s contact based. And changeable. And is meant to convey the idea of changeability. Not here’s a display of my abilities, sit back and passively judge them, or passively appreciate them.

KP: Yeah, of course not. And kind of getting into… you mentioned something like intonation and emotional content. I mean that comes in different forms… I guess do you have thoughts and feelings behind why you might choose lyrics or words in one thing and non-textual vocal sounds in another?

CC: Sometimes when I was doing live performances I was bringing some preselected texts. Most of the time my own or occasionally things other people had written. So occasionally there’s that decision made beforehand. Other times there would be… it would be open in my mind. I just started doing this thing where before I was playing live I would be thinking… the entirety of my preparation would be thinking about maybe a set of ideas or feelings or topics or something kind of like in a circular way. And then getting to the venue, whatever place I was playing, and then seeing how I felt there, and then seeing which of those feelings or ideas made sense or seemed to apply to the situation that I was presently in, and then leaving it open as to whether or not I would use any of those phrases, words, or just sounds, in a given performance. Those two things, Offer and Two Times, are the first things I had recorded on my own since 2017, really since 2013 or -14. But the words, the short phrases came out completely spontaneously.

KP: Yeah, I think “I’d like to walk to you” is one of them?

CC: “I’m going to to walk to you,” I think [laughs] I’d have to go back. I think it’s “I’m going to walk to you.”

KP: Do you ever feel like words’ sometimes fixed meanings or relatively rigid definitions are a barrier to their use beyond not necessarily vibing with the environment that you’re singing in, like the way they sound?

CC: I guess the main thing I do with words or lyrics, on the one hand I tend to use things that are super open-ended, and that’s how I really started writing. And my conception of writing… when I was young, the very first thing I wanted to be, there were two things that I very first wanted to be as a child, one was a novelist and the other was an entertainer and then later shortly after that I wanted to be a visual artist. The whole issue of writing has been there from the very beginning. And impatience with detail. In high school when I was really thinking about writing I was conceiving of trying to write without detail. Extended things, like short stories and novels. But never really did that. Just this concept of how can generality or ambiguity be maintained and so I play around with that a lot. On the other hand I became fascinated with this idea about kind of the opposite, of super detailed… or details that you wouldn’t ordinarily think of being worthy of being in songs but minus a kind of narrative, like short story telling in a song, not that. So how do you incorporate all of these details… it’s more like a kind of poetry idea. I don’t think it’s a - your original question, is it a block, is it an impediment?

KP: Yeah, are the meanings of words sometimes an impediment to using them if they’re clashing with the space that you’re singing in?

CC: mmm, no. They’re my words, so no. There’s an impediment to singing other people’s songs, for sure, on top of the other impediment of I’m not good at it. Having to execute someone else’s melodic structure, note structure, how it goes from place to place, it’s not easy and I’m not good at it. Not an interpreter of songs. But if I was trying to do that then that would definitely be an impediment to me and things where I have used other people’s lyrics I’ve purposefully chosen those where I can say that I feel that I understand them.

KP: Kind of on the flip side, for the non-verbal vocal sounds, the information in intonation, do you feel like that… or in what ways might you play with that? Or is that ever an impediment somewhat similar to the definitions of words? Like I know Alex will tell me, your voice went up and down this way and this is how I’m interpreting that and I’m like, that wasn’t what I was thinking at all, this is how I meant it.

CC: I don’t understand.

KP: So similar to how words carry meaning through definition, non verbal sounds carry some information through intonation and I guess if the associations that we have with some intonations, if that sours some combinations for you.

CC: I mean immediately I think of something really easy, like certain sounds may be conveying emotional content to people like anger…

KP: Exactly, like if there might be something associated with anger but you wanted to explore it just for the sound, does stuff like that clash?

CC: I don’t think I ever go into something with a preplanned, I want to express anger, joy, whatever. The main things for me, the two main things that are challenging to deal with - but I also try not to let myself worry about them too much, because why, it’s self-defeating - is what I was talking about earlier, not sounding mechanical, not sounding like I’m performing a bunch of cool sounds, or here’s a series of wow I can’t believe someone can do that with a human voice. That’s antithetical to what I want to do. Like, oh wow crazy sounds, amazing, one after another, can’t believe a person can do that. In fact I would much rather, if I had to side with one way, I would much rather side with, oh wow it’s so interesting, those rather normal sounding sounds, how odd they can become or how strange they can make me feel, I can imagine anyone making those sounds, it doesn’t take some special ability or some special singing technique to pull them off. The other thing that’s challenging for me is the aspect of unintentional imitation or sounding like another vocalist who I admire, who was before me, who I listen to. Examples would be Julie Driscoll, or Julie Tippetts as she is now known, or Yoko Ono, or Patty Waters, or Linda Sharrock, and others that are lesser known, who shouldn’t be. Sheila Jordan, on and on. Jeanne Lee, huge. So I recently heard - I can’t remember what it’s from and I can’t remember what it’s called, so I can’t tell you so that people can hear it if they wanted to but - this recording where I really went, oh my god it’s so similar, I’ve done something so similar to that, before hearing it. I was like, oh that’s really weird, it’s almost like I absorbed the implications of her singing and approached something with the same idea. And so that, I’ve heard things where I’ve been like, oh yeah that sounded like Patty Waters, or that sounded like Julie Tippetts, that sounded like Linda Sharrock for a little bit there. On one level it bothers me and on the other hand it’s interesting. It’s like being resolute on the side of practicality, right. Because what’s the point of… you just become aware of that possibility and I try to integrate that understanding. I definitely want to find my own voice, and I think I’ve succeeded at times. It’s like accepting… some people might choose the word failure or weakness of your body of work, while keeping going forward and recognizing, I mean objectively recognizing where you are unique and trying to go further in those things. So those are the two main things for me.

KP: I guess since we’ve talked about how the voice is part of the body, very embedded in it, and just with the daily familiarity of it too, I feel like it feels, more than other instruments or tools, it feels very close to the self than others so if you are using the voice that is so close to you, whenever you feel like there is a failure - whatever that may mean in the moment - or perhaps unintended sounds, does that tend to sting a little more than say something like guitar?

CC: No, it’s not like it stings it just…

KP: acknowledge and move on

CC: Yeah, be aware of it. There’s no perfection, it’s not a competition to see who can be the most original vocalist ever in the history of time or in a decade or even whatever, it’s just a sincerity about… it’s about finding out about myself and kind of relating that to other people as a shared thing that we all do. So then it becomes more than just about myself, about finding out about myself, this is what we do as people, is find out about ourselves and find out about others.

KP: and often through vocalization too

CC: Right. So finding out, oh sometimes I sound like somebody else and now I’m aware of that and that’s not really something I want to do. But I’m not going to then flip to this opposite concept that would be just as restricting, now I have to make sure I only sound like myself, I will never do certain sounds, I will never sing a certain way, I will never… now no more, whatever it is… that would be a false dilemma. Either/or.

KP: Yeah, it’s that complexity that you were talking about earlier, never poles, always a mix. And for similar reasons with the voice being associated with the body, is there an inherent intimacy in using the voice for music and is that sometimes something that you wish you could escape?

CC: I was thinking of something else, before I answer that question. I think really where I feel that I’ve done the most to… one of the things that’s most interesting to me is where the idea of wordless and words comes together and that’s when I feel like I sound most only like myself, when those two approaches kind of meet. There’s, to me anyway, unexpected phrasing and unexpected emphasis on certain words and the way they sound and the emotional quality they’re putting across to where… and so, do you know what I mean, the practice of separating those two things out, wordless and words, as a way of examining both of them, feeling them out, and then putting them together for me is maybe the ultimate experience.

KP: I feel like I can hear that happen. I’m not sure if it does happen with “I’m going to walk to you,” but at some point you begin with a phrase and then it slowly transforms into something that’s not words with changing emotion but it’s still understood as that phrase, and those steps in between is what makes it amazing.

CC: It feels like a… I don’t know it feels like an amazing kind of, yeah, I don’t know how to describe it. Playing a game in these kinds of things can have a connotation as too mundane. It’s like a spiritual game, or a spiritual challenge or something, an adventure. For intimacy, no I don’t ever wish to escape it. I think intimacy is one of the most important things about music. It’s difficult sometimes in the whole context of the entertainment industry, music business, whatever how it’s set up and how people think about it and how people talk about it and approach me about it with certain kinds of concepts… there’s a whole lot of implicit assumptions that happen quite a bit. And being on stage and things like that, and what people think about it. The challenge of really showing… it’s impossible right, when I sing in front of people it’s not ever really 100% the entirety of my intimate self, that’s impossible. There’s always an aspect of it that’s… and that’s a whole other factor we could bring in, which is the idea of performance and acting and how that integrates with concepts I was talking about like truth. But the concept of intimacy is really important. And no it’s not something I dislike. Sometimes it’s something that I didn’t want to play live at first, it was way too much, the energy was way too much, it’s just something I had to learn how to control better.

KP: I’m visualizing one of those triangles where you get to pick two of three or whatever and if you want to maintain your sanity with that intimacy you can’t go with the “productivity” levels that go with “career” musicians, so you approach performance on your own terms.

CC: Yeah I don’t think…. The whole idea of the productivity and work ethic like that, I don’t agree with it on any level, even regardless of that concept of intimacy. I just don’t. It’s totally against what I think and what I want to do and how I want to participate in it. Album cycles, tours supporting albums, all of that music business stuff. Have I ever toured on an album? Yes I have. On the other hand I haven’t several times. It’s not that I think I would rule it out in every instance, but in general I don’t believe in forcing what I do into somebody else’s time schedule or pattern or demand for…. I don’t like the idea on any kind of level of this is just what you do. You’re a musician. If you’re in a band, this is just what you do. Xyz, and you better get used to it. And no matter how you feel about it, no matter what it does to you, no matter what it does to your life otherwise, no matter what it does to your emotional and mental health, no matter if you philosophically disagree with it, well it’s just what you do, you gotta do it. No way. No how. One of the points of being an artist is to get away from all of those things, to me. If I wanted productivity schedules I would have been, I don't know, whatever. I would have chosen to do something else.

KP: And I guess with not just being one thing and also you mentioned your early interest in writing and art earlier too, I know you do poetry as well and some watercolors and I guess just starting with the poetry, is there a difference between lyrics and poetry to you?

CC: Yeah there is, and especially if one is approaching it like a songwriter. I think there is but it’s hard to explain what it is and there’s all kinds of caveats but on the other hand I don’t write songs so to me maybe it’s a little bit less… it’s all a big blur with me. I mean I can look at something that I’ve written down and know whether or not I want to sing it, to a certain extent. There’s things that you can manipulate like, if this is going to be on the page I would leave it this way, I would leave these words in and this is the way it would look. If I was going to sing it, I would extract certain word groups and maybe change words or whatever. Everything I do is like a pool of resources and then moving them around. Allocating the resources to use an economic phrase [laughs] I’m laughing because our society is so absurd, right? Everything that we do, all the ways that we do things, most of it is so absurd, it’s horrifying and also funny and depressing at the same time. It’s not cause I think it’s not cool, I just hate the language of economics. I don’t like referring to what I do with that language but then it just comes out because everybody talks like that. That’s one thing which is more problematic to me, which is how artists are talked about or how I talk about it myself and I hear myself saying things in certain ways that I don’t like, I don’t appreciate, and I wish I wouldn't talk that way ever.

KP: Yeah there’s kind of like an entrepreneurial vocabulary that’s leaked in. I think some of that’s old too, like the way music reviews - and there are people that still do this as well - view themselves as a consumer guide. They’re not really there for the music in some cases.

CC: Yeah it’s an industry catalog or whatever. It’s all about what we’ll put in front of you for you to consider buying as opposed to an exploration of possibilities. Of just, wow this is all really incredible. Isn’t this amazing. But what people do it’s more like a catalog, an advertising catalog. I don’t know, I don’t read any music magazines like that anymore. I did when I was a kid for sure. Partly just because I’m such a reader. If put in the circumstance I will literally read anything.

KP: [laughs] nice. Going back a little bit to the visual art bit and specifically the booklets that you offer with Offer and Two Times, I found that they were super tactile. I feel like people talk about the texture of strokes and stuff like that, but it was refreshing to have a booklet context where you can actually feel the strokes. I dug that some images are pressed into the other side and because they’re flowers it’s like pressed flowers. And also because of the pressing there’s a lot of almost-duplication on sides but other pages where it looks like there’s a continuation but it’s actually painted that way. All of that is to say, are there ways in which your visual art and your singing communicate to each other?

CC: I really started doing art before I started doing music. I don’t know. In a way, I haven’t really thought it all out, how it all relates to each other. Part of that is that I don’t like to explicitly say a lot of things to people about how I think they should receive my music or my releases but part of the intention of the CDrs that I did and the artwork that came with them and these booklets and all this sort of thing is that they’re changeable. You could if you wanted to cut the string that holds that booklet together and re-sort the pages. You could take them and use them for other things. You could whatever. For the CDrs it was like that too. A lot of them were wrapped. You could wrap them differently. They weren’t intended to be these hands-off art objects or anything. I was thinking about it like a combination of what people do when they have keepsakes, like birthday cards or christmas cards or something that they have kept over time and that stay in boxes and maybe get all smushed down and weird. Or even though it’s an important thing they cut it up and make a bookmark out of it or something. Because it’s an important thing they make a bookmark out of it that they can actually use all the time. And it eventually gets lost… something along that order. They’re a representation of this contradiction between these lasting and ephemeral things.

KP: Kind of fitting with your music too it felt… I mean, I know it was actually intended for Alex, but it feels more than just a CD in a jewel case, it feels like an intimate exchange, probably because it’s more of a shared experience rather than just a mass produced thing.

CC: Yeah and not a mass produced thing but also not a collectible art object. They’re not meant to increase in value because they’re art or whatever.

KP: Yeah, not getting into the nft space [laughs]

CC: I have no… I don’t know anything about it besides these weird things I see. I have no interest in all that stuff. I’m sure eventually I’ll be forced to learn more to a certain extent, just with it increasingly being around me, nft, blockchain, whatever. It very little applies to my life. I don’t know, maybe I’m wrong. I don’t know whether this is ridiculous on my part but increasingly I find it more and more important to tell people musicmaking and artmaking isn’t necessarily a pursuit of the well-heeled… like I’ve never made a lot of money from music, even on the labels that people think you make a living on, I never have. I don’t own a house, I never will. I don’t own a car, I probably never will. I don’t have assets - I have a three-thousand dollar ira and that’s not even… because I’m in debt. All this weird zone of financial stuff, manipulation, monetizing things, and all this, I just don’t know, I never wanted to deal with any of it. I had to finally figure out that it was really dumb that I wasn’t participating in my work’s ira because I was basically just turning down wages. Up until I realized that I was just like I don’t even want to know, I don’t want to figure it out.

KP: Just getting wrapped up in the whole financial web. But yeah, I think it’s important for people to hear, you do it because you want to do it, not because you want it as a platform to make a lot of money.

CC: But also there’s the opposite side of that which is this idea that, well people do it because they want to do it and they’ll continue to do it no matter the circumstances, no matter how they’re treated… and that’s the other side of it that’s wrong also, because I have almost stopped doing it many times because of how hard it is to do because of still having to work a job in which, you know, whatever. I am better off than a lot of people in this country because the minimum wage is so incredibly low and people are so exploited that it’s just unbelievable and disgusting, but it’s still hard. I don’t know. That whole side to it, what do we… what kind of society do we expect to have and want and what are the messages that we give people about what artmaking is and why people do it and why they pursue it and why they shouldn’t and what’s the role of the community around it. All those things are complex, it’s fraught, it can get really argumentative. But my main thing is I feel like that people who are outside of it, who aren’t involved in any day to day way as far as being somehow connected with people who do it personally or somehow work in some capacity within it is that from the outside it may look as if there’s a lot of money involved but most of the time there isn’t and a lot of people are struggling within it. Feel driven to do it and still struggle within it. A lot of people don’t. A lot of people drop out. I’m aware on the other hand though that compared to other problems people have maybe that’s, you know… I don’t know, it’s complicated. But where there is a lot of money involved in it, that’s also obscured. Where there is the corporate stuff involved, that is obscured as well. The lack of money and the presence of money.

KP: Just the concentration that you see, like political systems, capitalist systems, it just gets concentrated in a few hands…

CC: Yeah. But I don’t know. For a long time for lots of other reasons that have nothing to do with any of this stuff just… it’s hard, this society is difficult, for a lot of reasons, and then you add financial stuff. I questioned for a long time of whether or not to put… for me to be the person who’s putting my music online and where. And had questions about every single platform. And it’s fallen out that bandcamp is the best option that there is, so that’s what I started doing. In the hopes too that maybe in another five years I won’t be working full time. Maybe I will go back… I mean I had a five year period out of thirty where I wasn’t working another job. I’m getting older. These are all considerations for artists. Aging is a big one.

KP: Yeah, just to wrap it back around to the voice, a viola or something might age like wine but the body does not, right. We age degeneratively after a time, we get sick, we suffer injury, our weight fluctuates. If you would be comfortable with it, in what ways has your voice changed through the decades that you have been singing and in what ways have you changed the way that you approach using the voice with those changes?

CC: No that’s not bad to ask at all. That’s interesting, I’ve been thinking about aging a lot. I’m 53, I’ll be 54 in November. Well there’s a whole bunch of different things. Its funny because I used to smoke and I used to smoke on stage while performing back when you could still smoke in clubs all over the country. I try to put myself back… there was a place in Memphis, somehow you can still smoke inside of it, and they were going to agree to have us play at a point in which there wouldn’t be enough people there to have it be that smoky inside, but I couldn’t even stay in the room because of the smoke just in the furniture, and the drapes, and the carpet. It’s unbelievable, you could smoke inside of clubs and I used to smoke when I was singing. I stopped smoking for good about eight years ago, ten years ago. I wish honestly I could say there was a huge difference and how my voice feels to me and what I can do between those two things, being a smoker and not, but no, oddly, weirdly. Not an endorsement of smoking at all, you can fool yourself into thinking it’s not doing anything bad to you if you rely on certain effects, or lack of effect. I don’t think… I’m looking forward to finding out how it goes. I’m looking forward to the whole experience of getting older and older and older and continuing to sing and seeing what that’s like. So far, I don’t think… I’m starting to be more in touch, but I have been really out of touch with the whole concept of aging because for a lot of different reasons I’ve always looked younger than I am. I was just looking at a picture someone sent me and I’m thirty… almost forty in it and I really look like a teenager still. Or early twenties, you know. And I don’t have kids, so I haven’t seen aging up close like that. Witnessing somebody else dependent on me or extremely close to me also getting older and how obvious it is, a child’s aging. But I’m starting to notice it in myself. Weird how parts of your body age faster than others. Although I’m not interested in the classical repertoire at all, but somebody said to me well you could have been an opera singer and I was like, no I couldn’t because I don’t have interest at all in that whole extremely difficult process. But I’ve read about how in that kind of singing you get to a point where there’s certain things you just can’t do any more and it really impacts what you’re able to do. Since my thing is so organic I imagine it’ll just take me, it’ll lead me, it’ll be a cooperative journey between my body and my mind as to what happens, what I’ll do.

KP: Yeah. I’m trying to think of singers and people like Joanna Newsom and Nina Simone and Nahawa Doumbia are coming to mind as singers who I’ve noticeably heard age across record and it’s always a fascinating journey. To put an aesthetic evaluation on it, I always feel like there’s a certain richness to the aged voices that’s embraced.

CC: Yeah, I love that. I mean someone like Billie Holiday, where I prefer the older so called… I don’t know if there’s a reevaluation but whenever I started listening to Billie Holiday the old line was always, her voice got bad as she got older, the jazz point of view or whatever. Which I never agreed with. The mind does so many things… I feel much more able to deal with the world, physically, older, like I feel much more stamina, I was much less strong when I was young.

KP: Yeah, I was horribly coordinated as a kid and I feel like that’s come with age.

CC: Same. In fact I got a report card that said I had poor motor control and I was taken… I don’t know if it was my parents’ idea or if they were advised to take me to a place, like a medical expert, specialist, to go through a series of tests to figure out whether I was “normal.” As far as I know I was quote unquote normal. But it was like, why can’t she tie her shoes and why can’t she hit the ball. Maybe why isn’t she interested in even doing any of those things. But when I was earlier, getting up in the morning, being at work, standing up all day, it was really difficult and I think touring helped a lot with that too. But anyways, so, looking forward to that. I think it’s gonna be super interesting. I haven't gotten to the point yet where I consider or I worry about what about the time when I am physically unable to sing or play.

KP: Not even halfway there yet hopefully…

CC: I keep telling people I had a dream that I was… I don’t know, there’s a party or some kind of celebration and I, me, now was standing on the side watching this event and I figured out it was me receiving some kind of card or award, something to do with turning 104 years old. And I was like, oh that’s a good age to live until. So hopefully I’ll get there. In that case it is about half. Probably not. I don’t know, it’s bizarre, because most likely… I don’t know, biologically, I’m adopted, so I don’t know the age of any of my biological relatives, what their age is when they died, I don’t have any kind of information like that. But just thinking about how I was a smoker and just, whatever, all of my drinking and eating meat, all those different health factors, knock on wood I’ve got maybe like twenty, twenty-five, thirty years if I’m lucky. And that’s like, the past twenty-five years have passed so quickly. So that’s pretty wild and I’m conscious of it. But I’m still not to the point where I think…. Maybe I won’t, maybe I will never stop, I don’t know. Somebody like Chavela Vargas, she performed into her, I wanna say, nineties.

KP: I think you’ll be pleased to know the oldest woman that I’m aware of was a French woman who enjoyed daily cigarillos and swore by her daily thimble of whiskey so you should be alright.

CC: That’s good. I’ve just gotta get certain things in line with my life like I said. It’s just a fact and there’s a lot of people in my situation. I’m economically insecure and I have no family, zero, I’m not going to inherit anything, so I’ve gotta figure out some things that are extremely practical while at the same time being an extremely not practical person. I've always been not very… on the one hand… on the other hand here I am and I’m OK so I must be able to cope with reality to enough of an extent to get by.

KP: Well, did you wanna talk about anything else, about your vocal practice, total practice, or any other direction that you wanted to go in?

CC: I don’t know. I guess one of the main things that I think has affected me a lot is the sort of bifurcation between somewhat serious and pop music and I’ve never considered what I’m doing to exclude either or be… you know, I’m not just saying pop songs or whatever but the whole realm…. I’ve just never… it’s been a challenge to be understood for that reason. I don’t really fit into either world completely, if we can simplify it into two main worlds of whatever, high art, low art, academic, non-academic, experimental, popular, classical, popular, sound art, music, whatever, you know, the split. And even then, on the ground to me it seems like, where I came up on the ground it was always blurred and non-distinct with people going back and forth and taking inspiration from both, all different kinds of worlds and levels and whatever. But it seems to me there’s still a line and it’s still a barrier and it’s still I don’t know… so I don’t think of myself as having a practice, exactly. I feel like I do a lot of it in my mind, where there’s no explanation necessary for me and there’s no reason to parse it out into a regimen. In a lot of ways, to enter into the worlds in a deeper way of… outside of the whatever, underground clubs or whatever you want to say, you have to have explanations and you have to have a regimen and a rationale and a blueprint and a way of talking about things that I never… I just don’t… like even when I used to keep a diary I was so bored with the whole idea of, you write on page one and then you write on page two about what happened today and then you write on page three about what happened on the third day. I started skipping around in the book so if you read it from front to back it would be nonlinear. However long it was, say five months, you wouldn’t be able to tell what happened from day to day, you would only be able to tell the totality of those five months rather than… and it’s just so much more interesting for things that I do, to me, it’s more interesting for me for things that I do to be open in every way. I’ll go months without singing. All the while, thinking about it. On the other hand there was a place that I was living that had a really cool back yard that was surrounded by trees and there was owls and I used to go in the back yard and sing every night…

KP: Screech owls?

CC: I don’t know, owls. They made owl sounds. I never really saw them, it was dark and they were in the trees. I just heard them and I knew that they were there. They would just talk to you. I used to sing there every night but then I moved and there wasn’t that place anymore so it’s not like I’m still going to try to sing every night in a place where the neighboring house is like three feet over and there’s no place that makes me feel that way. So, so much is dependent upon reality. And unfortunately, or fortunately, I don’t control my reality to the extent that people with more money do.

KP: Yeah. I guess from an outsider’s perspectives it’s not about the frequency of performance or the frequency of releases or whether you’re in NYC and have performed at such and such a place. You strike me as a person that has strong thoughts and feelings about what they do and that’s taking it seriously enough. That’s all that needs to happen. That’s it. And then it’s on the listener... I don’t know…

CC: I would like for listeners to approach it with an open mind. And I would really like for writers, listeners, anyone who’s thinking about it, to really approach it with an open mind and realize that the categories that maybe they've been told things are or go into aren’t necessarily accurate, or don’t reflect necessarily what the person feels.

KP: In this case categories are usually sales things right.

CC: Usually, usually. I think there’s a little bit more to do with it but usually they’re about marketing. But my point is that there’s people who swear up and down that its absolutely 100% necessary to have a daily practice, to have a practice regime, to kind of put your body, and your instrument, through these paces consistently. And if you don’t do that then you’re either not serious, or you’re not going to be good, or you’re not dedicated, or you’re not going to accomplish anything, and that’s absolutely false. There’s all kinds of ways to go about being an artist. And there’s nothing wrong with being an artist. There’s this other weird push to completely, I don’t know, denigrate it as a category, or to make it seem not useful to people. You’re a technician or you’re a…

KP: content creator

CC: Yes or you have a skillset and the most important thing is to develop your physical skillset and put over that skillset and as it seems from the concept of the artist which encompasses that but isn’t only that. I mean there’s an intangible aspect to it that sort of like a yearning or a reaching aspect that I think a lot of people are very cynical about. A transformative aspect. A lot of people I think are distrustful of those kinds of ideas. But without them, I don’t know. At least not taking into consideration that they’re part of it leaves something very important out.

annotations

annotations is a recurring feature sampling non-standard notation in the spirit of John Cage & Alison Knowles’ Notations and Theresa Sauer’s Notations 21. Alternative notation can offer intuitive pathways to enriching interpretations of the sound it symbolizes and, even better, sound in general. For many listeners, music is more often approached through performances and recordings, rather than through compositional practices; these scores might offer additional information, hence the name, annotations.

Additional resources around non-standard notation can be found throughout our resource roll.

All scores copied in this newsletter are done so with permission of the composer for the purpose of this newsletter only, and are not to be further copied without their permission. If you are a composer utilizing non-standard notation and are interested in featuring your work in this newsletter, please reach out to harmonicseries21@gmail.com for permissions and purchasing of your scores; if you know a composer that might be interested, please share this call.

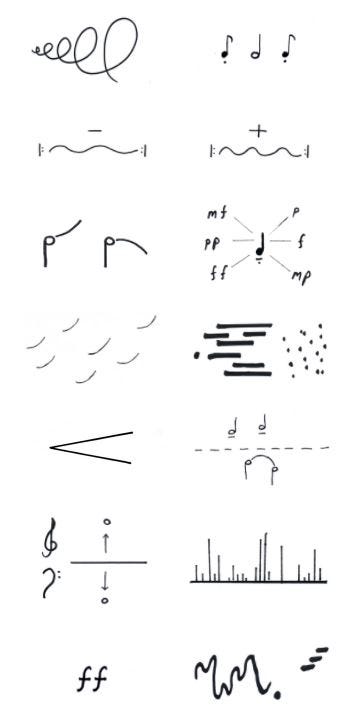

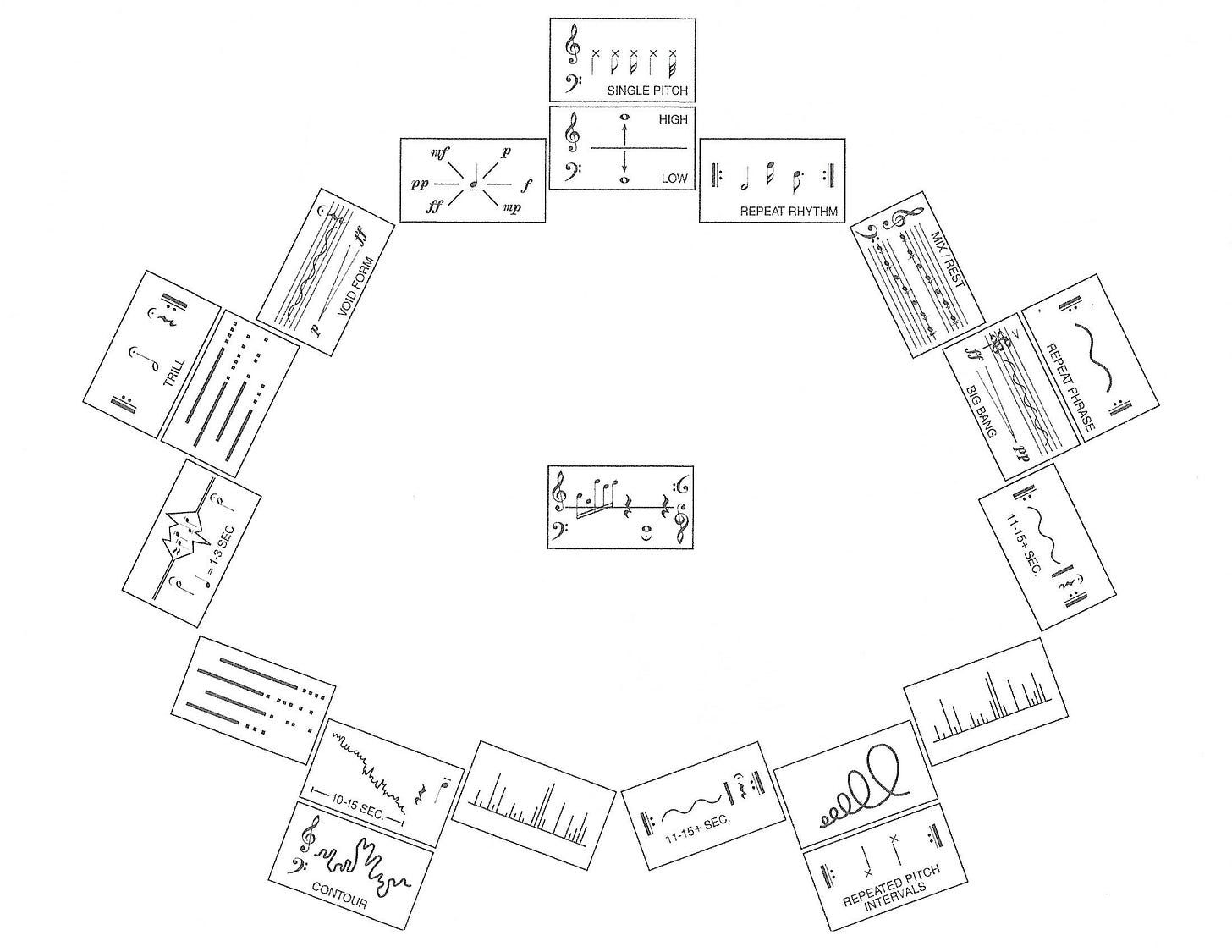

Bruce Friedman - O.P.T.I.O.N.S. (2004-)

Essential considerations

1. The O.P.T.I.O.N.S. Graphic Musical Symbols (cards) can be arranged in any order.

2. A card is a musical event. It can be played through once or any number of times. Once through a card would have a ‘linear’ effect. Many times through could result in a textural sounding event.

3. Card events can be repeated in a score if preferred.

4. Cards can be ‘overlaid’ for simultaneous performance.

5. Rules for interpretation of each card symbol are up to the musicians at hand (or instructor). It is perhaps not advisable to have two differing interpretations for the same card in the same compositional improvisation.

6. Durations and tempos for each card ‘event’ are up to the musicians at hand.

7. Cards with rhythms are not to be interpreted literally, but rather as a suggested rhythmic unit, freely placed in sonic space according to preference. The rhythmic order is not flexible, but pitches applied to the rhythms are flexible. That the notes may appear upward or downward is not important. Repeating pitches may or may not be effective.

8. Cards do not have to be interpreted literally but could be a ‘jumping off’ place for improvisation.

9. Sometimes a conductor is useful if only to cue card changes. Or perhaps finer musical considerations such as dynamics.

10. The + and - symbols are for expansion and contraction, or elongation and diminution. For example, a repeated motive could be broadened by adding notes or length to already existing pitches.

11. Many of the cards are similar. Select any of those that are musically intriguing. Feel free to design your own additional symbols also.

12. The ‘scales’ card is simply a suggestion to incorporate traditional Jazz or Classical approaches as pitch sources.

Bruce Friedman is a trumpeter, performer, improviser, and composer based in Los Angeles. His working groups have included: Surrealestate with Jonathon Grasse, Ken Luey, David Martinelli, Jeff Schwartz, and Charles Sharp; Decisive Instant, an ensemble focused on music with non-traditional notation, with David Adler, Derek Bomback, Alicia Byer, Jonathon Grasse, Bill Harrington, Robert F. Leng, Ken Luey, Jeff Schwartz, Charles Sharp, Breeze Smith, Tom Steck, and Douglas Wadle; Hyperbolic Quartet with Haskel Joseph, Breeze Smith, and Darryl Tewes; Coldwater Trio with Haskel Joseph and Michael Intriere; duos with Motoko Honda and Scott Fraser; and other frequent collaborations in various constellations with Rich West, Ben Rosenbloom, and Alan Cook, among others. Forthcoming projects include an adaptation of Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Tierkreis for trumpet and two guitars on MINUS ZERO, a second duo with Scott Fraser, and another interpretation of O.P.T.I.O.N.S. with Derek Bomback and others. For additional listening samples, please visit Friedman’s webpage for recordings or bandcamp. For additional information, please visit his website or facebook.

O.P.T.I.O.N.S., or Optional Parameters To Improvise Organized Nascent Sounds, is a collection of over fifty cards containing standard and non-standard notation to be arranged and interpreted with substantial latitude according to the considerations above. Perhaps the strictest is the seventh consideration, dictating that rhythms are not to be interpreted literally and that their order is not flexible. But more often the considerations guide towards freedom in interpretation, going so far as to suggest a card can serve as inspiration for improvisation or that new cards can be invented. Friedman’s webpage for O.P.T.I.O.N.S. generates a random arrangement of twelve cards from a subset of the full suite for a readymade score. Daniel Barbiero’s interpretation for contrabass and preparations composites scores created using this method. Photocopies of the full suite of cards by the composer are available by contacting the composer. A recording guided by Friedman and performed by Emily Beezhold (keyboard synthesizer), Ellen Burr (flutes), Jeremy Drake (electric guitar), Friedman (trumpet), Michael Intriere (cello), Lynn Johnston (clarinets), Haskel Joseph (guitar), Richard Kim (violin), Andrea Lieberherr (violin), Eric Sbar (euphonium), and Rich West (percussion) documents the system in an ensemble context with space for improvised solos and can be previewed and ordered here. O.P.T.I.O.N.S. is featured in Theresa Sauer’s Notations 21.

The soul of O.P.T.I.O.N.S. is in its permeating mutability. Card arrangements can be prescribed via the random generator or built out in infinite custom formations. Organized according to the comforts of the performers or to purposefully subvert them. Unbound by any sound result, realizable as a slow and silent classical music or a swinging and dense jazz or something else. With an eye towards the changing spatial relations of sound in arrangers’ ability to fluidly shape the composition itself. In suggesting interpreters create their own cards, the ideals of the composer and the work-object diffuse into others as the system expands. And though it is suggested an ensemble converges on a shared interpretation of a given card for a performance, interpretation is not necessarily fixed. Indeed, the interpretation of a card might necessarily change contingent upon the card with which it is stacked, the cards temporally before and after it, or whether it is alone. Unfixing or unstandardizing standard notation by underscoring its shifting relations to surrounding actions or to tensions in directions for a given composition might cultivate a diachronic, listening-focused approach to performance.

reviews

Alvear-Bondi - sin título #26 [Nicolás Carrasco] / Ground in Cis [Anna-Kaisa Meklin] (INSUB, 2022)

Cristián Alvear and Cyril Bondi perform a Nicolás Carrasco composition with electric guitar, percussion, and pitch pipes and an Anna-Kaisa Meklin composition with electric guitar and harmonium, joined by the composer on viola da gamba, on the 51’ sin título #26 / Ground in Cis. It is the second in a series of three recordings showcasing performances of compositions from Chile and Switzerland commissioned by Alvear-Bondi, preceded by performances of pieces from d’incise and Santiago Astaburuaga and with a forthcoming release featuring pieces from Bárbara González and Mara Winter.

Guitar and percussion move through motifs together yet separately, as if in their own times though trying to relate, one lingering awhile longer while the other goes elsewhere, close but out of unison in some secret rhythm on the half-hour “sin título #26.” A structure sounds might mimic, staccato tones for staccato tones, or more complex chords for percussive systems like something sounding like a rotational shaker, or these complex systems for harmonic depth in singing metal and resonant guitar, together in feel but distant this time in timbre or provenance. Like their movement is just mismatched, so too they never foster beating patterns together though the phenomenon is not rare here, ones luster dulled by truncated decay or muted material while the other’s ringing, and this sense of missed harmony recalls the distance between the performers if the desynced cadences did not already. Two hearts beating as one at different times, in different places. One motif I keep thinking about sounds like a slowed and subdued “Ascension Day” climax of crashing chords with the resolute hammering of metal.

The 19’ “Ground in Cis” is a mellow guitar melody trilling among the balmy harmony of viola da gamba and harmonium beating, seeming to push and pull to break into braiding melodies, followed by guitar following viola da gamba in its melody, quickening, tumbling together, while the harmonium solos, deflating, creaking. Reminds me of a kind of love triangle narrative.

- Keith Prosk

Ilia Belorukov - A Fluteophone In The Forest (Raw Tonk, 2022)

Ilia Belorukov performs on the alto flutophone alongside environmental noise in the forest of Vologodskaya Oblast.

“A Fluteophone [sic?] In The Forest” - indeed, no more and no less - a variety of sounds more ‘in’ or more ‘out’ - screeches, skronks, exploratory snatches of melodiousness - and then, of course, the forest: resonance affecting the sound of the flutophone; wind rustling through trees, maybe a bug flying close to the recording equipment. It’s perhaps trite to highlight the ‘juxtaposition’ of plastic instrument with ‘natural’ environment, but among the cheekily narrative track titles I can’t help but read “The Forest Echoes With The Sound Of Woodwind” with a sense of irony, especially after, in “The Forest Shelters The Breeze” and “The Forest Lets The Wind Whisper,” we really do hear the sound of wind on wood, rather than just this small pseudo-woodwind. The hyperactive flutophone does seem perhaps uncomfortable, overawed, in the context of the forest’s slow music, retaining a sort of dry sound in spite of the natural reverb, navigating its relationship to its newfound acoustic environment - a relationship to be understood, perhaps, in terms of a ‘return’ to a state of ‘child-like’ wonder (or complementary ‘silence’)? And the forest here feels less like a location than like a musical partner in Belorukov’s improvisations - or is it the flutophone telling a story about the forest, or even imitating or embodying the forest?

- Ellie Kerry

Laura Cocks - field anatomies (Carrier Records, 2022)

Laura Cocks performs five flute solos, with electronics and other objects, from composers David Bird, Jessie Cox, Joan Arnau Pàmies, DM R, and Bethany Younge - those from the last and first commissioned by Cocks - on the 74’ field anatomies.

Sounds elicit lucid images of tracks’ themes. “Atolls” a teeming ecosystem of SCUBA breath, scuffling crustacean key clicks, bubbling flute pizz pops, swift flights of chirps, and sines or perhaps undulating wind with this animalized flute to feel like a natural resonance with the environment, then densely overlaid flutes’ sour harmony, and screeching cries, and erratic last gasp spasms, and stabbing electric tones to seemingly signal the death of the reef. A balloon fitted to the flute interferes with the air of the performer on “Oxygen and Reality” for elephant roars, strained air grained like static, choked vocal multiphonics, breathless silent dream screams, gasping, and glimpses of some spoken space horror narrative in which there is no hope for more air. “Spiritus” recalls the ghost of the instrument in sonically blurring tremolo, ethereal harmonics, humming multiphonics, essences of the flute outside of the flute, like breath. “You’ll see me return to the city of fury” blustery hiss and heavy blow. And “Produktionsmittel I” a work of quickness and dexterity in an unsustainable technical whirlpool devolving into gasping, groaning, horrified sighs and tortured utterances among electric hum, industrial noise, some digitized datasong twinkling to an end only to begin again as if some poor soul passed by the expired one stumbling into the grinder of capitalist labor. Always a throughline foregrounding the relationship between breath as a mechanism for flute and for life. And in line with their direction of TAK Ensemble and TAK Editions, this portrait of the performer showcases tendencies toward the technical - kaleidoscopic in the colors Cocks can coax from the flute and the body - and the thematically political.

- Keith Prosk

Sam Dunscombe - First Study in Mass Plasma Synthesis (self-released, 2022)

Sam Dunscombe presents a 45’ track of thousands of sine wave oscillators tuned in just relationship and drifting.

Layers and volume might build and diminish but the density soon approaches saturation and confusion. Loud static dynamics and static texture. But there is rhythm in the swarm like phosphenes in the loud dark and while the abrasive overload never relinquishes singing sonic hallucinations sublimate from its ether. Drifting. Dancing. In flux. The complex beats of a barely there polyrhythm subtly shifting like an imagined community cultivating civilizations upon its creation by the musicmaker.

- Keith Prosk

Eva-Maria Houben - john muir trails (edition wandelweiser, 2021)

Percussion duo Katie Eikam and Kevin Good perform four Eva-Maria Houben compositions, with two versions of one, on the 38’ john muir trails.

All as soft and tender as percussion can be. For a third of an hour “in the fullness of time” alternates noise and silence, noises alternating a shimmering cymbal breaching singing sines, a ringing frictional metal twinkling like a bell and silence full of conspicuous birdsong, here small, sparse, more searching watching than abundant aviary, chirping in their own intervals. Its anthropogenic waves finding some natural resonance with wilder spaces. Evoking a feeling of the reception of nature’s wonder interrupted by consciousness and action. “no evil from ‘waste of time’” is a metallic clink and woody pop synced, just out of unison, small variations of an inner time, surrounded by silence, larger crows and owls or something like them. The two 1’ “so little a time” the clink and pop too, the larger birds too, but soundings are distanced and silences are impressionistic, the latter losing some songs presumably due to the time of day. “among flowers and sunshine,” its title now out of time, is a 10’ solo for marimba/vibraphone combination, taking the bee’s path among pages like flowers, in indeterminate order, not as the crow flies, which coincidentally is absent along with all the other songs for sirens, a kind of bird in its own way, alternating simple timekeeping with flowing mellifluous melodies, timeless. Like the watch to Quentin - “I give it to you not that you may remember time, but that you might forget it now and then for a moment and not spend all your breath trying to conquer it” - this music is given.

- Keith Prosk

https://www.wandelweiser.de/_e-w-records/_ewr-catalogue/ewr2117.html

Eva-Maria Houben - together on the way (Another Timbre, 2022)

George Barton, Eva-Maria Houben, and Siwan Rhys perform a Houben composition for percussion, organ, and piano on the 67’ together on the way.

An organ so low, calm, and consistent its ambient hum appears to fade into the very walls save for the slow deconstruction of its chord, muted howling emissions from some forlorn herald undulating within the wind. Generous in their spaciousness, rippling decays resonating among the faint pulse of the organ, blending, piano and percussion seem to move through motifs, exploring themselves and their relation to each other and to the organ in keys’ slow melodies, fluttering trills, inside-piano paw strikes, soundboard tapping, sonorous sinestral chords, thumps and knocks of various materials and ringing metals, each sounding illuminating the quiet like recalled forgotten memories reshaping a space to make their relation make sense, the moss on the stone, the dust in the light, the must of the air, distinct but in some seemingly synchronous waveform harmony, not what one or the other was, is, or will be but the convergence of them, together on the way.

- Keith Prosk

Masamichi Kinoshita - Ftarri’s Harmonium, Vols. 6 & 7 (Ftarri, 2022)

Kei Kondo and Tomoko Tai join composer Masamichi Kinoshita to perform two versions of Fierce Exchange and Accord III and Study in Fifths with natural horn, viola da gamba, and harmonium on the hour-and-a-half Ftarri’s Harmonium, Vol. 6. The twin trombones of Hiromune Ishii and Marika Tadokoro join the composer on harmonium to perform Count to 11!!, Fierce Exchange and Accord IV, and Study in Fifths on the one-and-a-quarter-hour Ftarri’s Harmonium, Vol. 7.

There is something special in listening to iterations of compositions, that makes them human more than some lithified thing. Makes me maybe more surprised than I should be to see how changing the instrumentation changes these compositions’ characters and, at least in the case of Fierce Exchange and Accord, how changing the structure appears to affect relatively imperceptible changes in the sound. Compared to the blending and mirrored gagaku/western instrumentation of shō and biwa/harmonium and guitar from the second concert which complemented the tricksterish spirit of Kinoshita’s clever number games, this performance with two trombones, shorter yet stretched in sustain, inverted to disintegrate towards silence rather than amass in density, lends an air of eerie alarm a la Grachan Moncur III’s most tensive environments. Similar changes in Study in Fifths, first presented at the fifth concert, convey shifts in feel and effect. The piercing and quavering twin flutes of I recalled traditional Japanese musics while the natural horn and viola da gamba of II lend a rustic rawness to their errant wandering - untwinned instrumentation further disconnecting the melodies even though they were always independent - and the clumsily sultry sliding of twin trombones’ farty deflation cannot escape the tragicomic tone of the instrument in III. And whereas the tremulous winds of I appeared to harmonize and beat with the revolving electronic tones’ waves, these instruments do not. The numbering of Study in Fifths might imply small structural changes beyond transposition but I cannot hear them yet, at least compared to the changes effected through instrument selection, which probably conveys more about my biases and failings than anything in the music.

Fierce Exchange and Accord presents a new composition among the series’ recordings and two performances of III and a structural extension in IV already allows comparative listening. It is silence separating staccato cells of brilliantly-colored and variously-shaped phrases in a membrane of sustained harmonium. Feels serial. Binary. Discrete. Not just in the sharp demarcations of sounding and silence but in the alternating approach to sounds that collide and sounds that accord. But like Study in Fifths, my ear loses the structural subtleties for the curious colors of the instruments.

- Keith Prosk

Petar Klanac & ensemble 0 - Pozgarria da (Belarri, 2021)

ensemble 0 realize a half-hour performance of the Petar Klanac composition, Pozgarria da, for eclectic instrumentation and four poems from Father Bitoriano Gandiaga.

Interludes a dialogue between a chorus of organs’ array of timbres’ radiant pulses and gamelan bell choir, harmonics throbbing together among them. Recitations of the Father’s Basque poems of gratitude flanked by flute strokes and string plucks and the frictional roar of hurdy gurdy alternate with interludes. In the quarter hour climax, spry organ motifs’ dancing melodies weave and refrain, with whimsy and with gravity, resound together, speckled by ejaculatory flourishes, arm in arm with hammered woody percussion and poetic interludes, ending in a dyad seesawed playfully with some timpani. It is a music that conveys the warmth of the sun in its pulse, the exaltation of life in its song, the refreshing smell and feel of earth in its calm pastoral. A musical translation of the Father’s words shamelessly expressive of beauty’s unbridled ecstacy, grateful for the joy in the easter of every day, spreading like a smile.

- Keith Prosk

ensemble 0 on this recording is: Fanny Chatelain (voice); Sylvain Chauveau; Denis Chouillet (organ); Melaine Dalibert (organ); Philippe Daoulas (rebec, nyckelharpa); Jozef Dumoulin (organ); Julien Garin (percussion); Stéphane Garin (gamelan selunding, hurdy-gurdy, tromba marina); Agnès Houlez (organ); Mark Lockett (gamelan selunding); Joël Mérah; Júlia Gállego Ronda (flutes).

Anna Lerchbaumer - Love, Lullabies & Sleeplessness (Eminent Observer, 2022)

Anna Lerchbaumer arranges two 15’ tracks for voice and objects on Love, Lullabies & Sleeplessness.

“No More Weekend (Sounds of Twins)” is two babies’ coos, coughs, cries, crawling, congested breathing, sneezes, squelches, spitups, hiccups, and panting collaged to sound naturally but also chopped and repeated rhythmically or overlaid for a harmony of cries. Briefly hear an older woman’s voice. There might be a division in understanding infant sounds as just something annoying and understanding them as a language of care, conveying information that might require various interventions for the vulnerable, and this track might further add an understanding of them as some musical language too. “Noisy Lullabies for All Ages (0–99)” appears to arrange the sounds of home appliances, button and switch clicks, wobbling, bubbling, humming, alternating, fanning, draining, vacuuming, vacuum-cord rewinding. The loud and ubiquitous drone of the modern home. Like the infant sounds I found myself keenly aware of the kinds of information with which each timbre is associated. Together these two tracks might present the musicality of domesticity. But the latter is not constructed to be overtly musical and might communicate, among these sounds of labor for the house spouse, a certain joy in the human that is not in the machine.

- Keith Prosk

Gabi Losoncy - Monday February 7 2022 (self-released, 2022)